In 1924, Trump Wouldn’t Have Had a Choice Whether to Release His Tax Bills

Every American’s income tax bills were once public record.

(Photo: Gage Skidmore/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for the presidency, has, over and over, refused to release his tax returns. This is apparently because of an ongoing Internal Revenue Service audit. After the audit is finished, Trump has said, he will release his tax returns. But it will be hard to know when Trump’s audit is done since the IRS doesn’t discuss individual audits. Which means that it’s possible we may never know how much money Trump earns or pays in taxes, or if he even pays taxes at all.

If this was the year 1924, he wouldn’t have had a whole lot of choice. That’s because back then, in the American income tax’s infancy, tax liabilities were a public record, accessible to anyone. Making public how much tax everyone was paying, the argument ran then, would help stamp out tax evasion. In addition, it might pressure voters to actually pay taxes, to avoid the shame of others finding out if they were not doing so.

It was a bold experiment in radical transparency, part of a fascinating age when newspapers regularly printed the exact tax liabilities of the country’s rich, famous, and powerful. How much did John D. Rockefeller pay in federal income tax in 1923? That would be over $7 million, or around $95 million in today’s money. We know because the New York Times printed it for all the world to see on October 24, 1924. They also printed some other rich people’s tax payments, like Charles Schwab, who paid $29,494.38, and J.P. Morgan Jr., who paid $98,643.67.

John D. Rockefeller with his son John D. Rockefeller Jr. (Photo: Public domain)

But 1923 and 1924 were odd blips in American tax history. They were the only years in the 20th century for which corporate and individual tax liabilities were public records. That’s because after something of an outcry, Congress dropped the requirement, mostly, President Calvin Coolidge said then, because it made the wealthy vulnerable to scammers if their addresses were public.

But making the individual tax records public didn’t exactly come out of nowhere. The first income tax in the United States, in fact, explicitly made that information public. That tax, which was put in place in 1861 and was originally drafted to pay for the Civil War, made the tax returns of every citizen public, according to a 2003 paper in the National Tax Journal. And this meant, like in 1924, that this information appeared everywhere, as newspapers routinely published lists of taxpayers and how much they had paid.

That income tax expired, though, in 1871, and, with it, any tax return records at all. It would be over 40 years before the U.S. had an enforced income tax again. In 1913, the American income tax finally came back, thanks to the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which specifically empowered Congress to levy income taxes. (An 1894 income tax passed by Congress was never enforced, in part due to the Constitution’s vagueness on the issue.)

And it was the Revenue Act of 1913 that installed what today we might recognize as a modern income tax. It was progressive, for one thing, meaning that the rich paid more, or seven percent on income over $500,000, while the poor paid very little or nothing at all. Income under $3,000 was not taxed, for example, and the first tax bracket above that started at one percent.

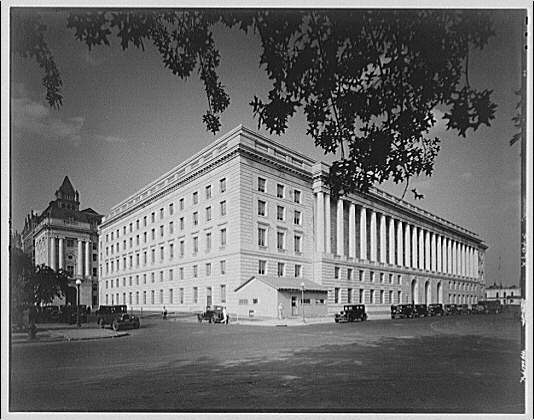

The headquarters of the Internal Revenue Service in Washington, D.C., circa 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Eleven years later, Congress made individual taxpayers’ information public, reasoning that doing so would help them fight corruption in individuals and corporations. ”Secrecy is of the greatest aid to corruption,” the Nebraska Senator Robert Howell said then.

What happened next was any newspaper editor’s dream come true, as David Lenter, Joel Slemrod, and Douglas Shackelford wrote in the National Tax Journal.

“Before the 1924 elections,” they wrote, “newspapers across the country published the names and tax payments of large companies, celebrities, and local residents. The New York Times filled pages with lists showing the amounts of tax paid by thousands of people, and ran stories listing the names of prominent New Yorkers who had paid no income tax.”

A high time for tax transparency, in other words, even if it might have been too good to last. President Calvin Coolidge, for one, hated that the information was public, and, in February 1926, succeeded in persuading Congress to reverse course, arguing—with little evidence—that releasing the tax information was doing more harm than good.

The issue would rear its head again deep into the Great Depression, when, in 1934, Congress again passed a law requiring taxpayers to disclose their tax payments. But after a faux-populist outcry President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a law repealing the measure before it even began. Tax returns and individual tax liabilities have been private ever since.

Even so, since at least the 1970s, presidential candidates have made revealing theirs somewhat of a tradition: every four years voters get a peek into candidates’ personal finances, as candidates voluntarily release their tax returns, mostly as a signal to the public that, financially speaking at least, they have nothing to hide.

If Trump doesn’t release his returns, he’ll be the first Republican candidate since Richard Nixon not to do so, even if, as Politifact notes, that didn’t turn out too well for Nixon. In December of 1973, during his second term as President, Nixon finally released four years of tax returns, asking Congress to examine them. They did, and found that he owed $476,431 in taxes, or around $2.3 million in today’s money.

It was a perfectly Nixonian self-own, in other words; we should find out soon if Trump is capable of something similar.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook