The Arcane Rules That Would Kick In If Trump Drops Out

If.

(Photo: Gage Skidmore/CC BY-SA 3.0)

As the 1972 presidential campaign wore on, George McGovern, the Democratic candidate for president, began hearing troubling rumors about his chosen running mate, Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton. According to the rumors, Eagleton had been hospitalized for depression and given electroshock treatments, treatments that up until then had been kept secret from the public.

By late July, it was becoming clear: McGovern had to do something to quash the rumors. And so, on August 1, 1972, McGovern did, asking Eagleton to step down as the nominee three months before the election.

A presidential or vice-presidential candidate had never quit a race in modern history before the Eagleton affair, but this year might offer an even grander political spectacle, thanks to Donald Trump. Ever since a damning recording surfaced of Trump talking about kissing and groping women against their will, Republicans have been expressing increasing nervousness about his candidacy, with many urging him to quit.

Would Trump actually quit on his own volition, having done the math and decided that bowing out now is better than losing by a landslide in November? Who knows! But we’ve never seen a candidate like him, and for someone who seemingly entered the race on a whim it wouldn’t be outrageous to see him exit in a similar fashion. On Saturday, Trump denied this possibility, telling the Wall Street Journal, that there was ”zero chance I’ll quit.”

The media and establishment want me out of the race so badly - I WILL NEVER DROP OUT OF THE RACE, WILL NEVER LET MY SUPPORTERS DOWN! #MAGA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 8, 2016

From the standpoint of Republican Party rules, Trump quitting, while unprecedented, would be easier than forcing him off the ticket. That’s mostly because the party’s rules clearly lay out what would happen next.

“The Republican National Committee is hereby authorized and empowered to fill any and all vacancies which may occur by reason of death, declination, or otherwise of the Republican candidate for President of the United States,” according to the GOP’s own Rules of the Party.

The rules go on to define a simple process of replacement: another vote by members of the RNC that could happen at a second national convention or if necessary, remotely. Whichever candidate gets a majority of the votes, wins the nomination. When similar talk of removing Trump surfaced in August, during his war of words with the parents of a fallen veteran, House Speaker Paul Ryan came up as the likeliest replacement. Now the debate centers around his running mate, vice presidential candidate Mike Pence.

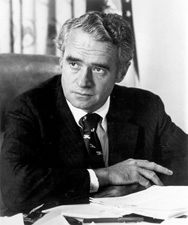

Thomas Eagleton. (Photo: Public domain)

A far trickier problem, however, are the actual ballots. And it’s that process, separate from the nominating process, where time is running out. In the U.S., each individual state controls the election process, from making and printing ballots, to counting votes on Election Day, to certifying election results.

Election law in the U.S. is a 50-state patchwork. From voting machines to filing deadlines, each state has different rules. And it’s the printed ballots—and even early voting that has already begun—that concern party officials should Trump quit. The closer it gets to the November election, the more state ballots will have Trump’s name on them, as state deadlines for certifying nominees’ names have come and gone.

It’s already impossible, in fact, to keep Trump off all 50. Most state deadlines to certify names for the ballot passed in September or early October, meaning that even if Trump quits today you’ll still be able to vote for him in many states.

The Electoral College provides additional sources of potential mayhem. Electors in most states are party officials, loyalists who have pledged to vote for their party’s nominee should they win a majority of that state’s votes. But should state party officials rebel, the national party would have little recourse to stop it. State parties could, in theory, nominate a different candidate for president, or make their electors unpledged, meaning that they are obligated to vote for no one.

George Wallace, left, attempting to block the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963. (Photo: Public domain)

This has happened only a handful of times in modern political history, most recently in 1964, when George Wallace, a Democrat from Alabama, ran against the incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson. That year, Democratic party officials in Alabama opted to make their electors unpledged, and Johnson’s name simply didn’t appear on ballots across the state. Instead, voters chose between Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee, and the unpledged electors, in effect handing the state to Goldwater, though Johnson won the election handily.

The system is designed to handle sudden jolts, in other words, even if the jolt is often a sign of a broader dysfunction within the country or a particular campaign. The results rarely turn out well.

When Eagleton stepped down in 1972 he was replaced by Sargent Shriver, an in-law of the Kennedys and the father of Maria Shriver. McGovern and Shriver went on to lose in November to the incumbent President Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, in what was then the biggest landslide in modern political history.

Update, 10/8: This story has been revised to reflect new developments.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook