How to Make an Alien Planet on Earth

For a short film about another world, the landscape designer Bas Smets created a dark, scientifically accurate terrain.

In Vila Nova de Famalicão, Portugal, just outside an unassuming house, sits a seemingly ordinary piece of land. A stand of mature eucalyptus trees towers over smaller, shrubby growth. Wild green plants blanket the ground. A grassy hill rises over a dry streambed, which winds its way through a cleared-out patch.

Look closely, though, and you’ll see signs of a previous iteration of this area. Tufts of jet-black grass poke through the ground cover. The dirt is mixed with ashes. Diamond dust glitters in the streambed. For four days in 2011, the land here served as the backdrop of the artist Philippe Parreno’s short film C.H.Z. (Continuously Habitable Zones). Years later, it’s still recuperating from a massive costume change.

The set-dressing project, known as “Landscape for a planet with two dwarf suns,” was created by Bas Smets, a landscape designer from Brussels. According to the architectural historian Marc Treib’s recent history of the project, Parreno and Smets met by chance, in a jazz bar sometime in the mid-2000s. What started as a conversation about the difference between “land” and “landscape” soon became a collaboration. In 2011, Parreno asked Smets for his help making a film about an alien planet, in which the “where” overtook the “who” or “what” and became the story’s main focus.

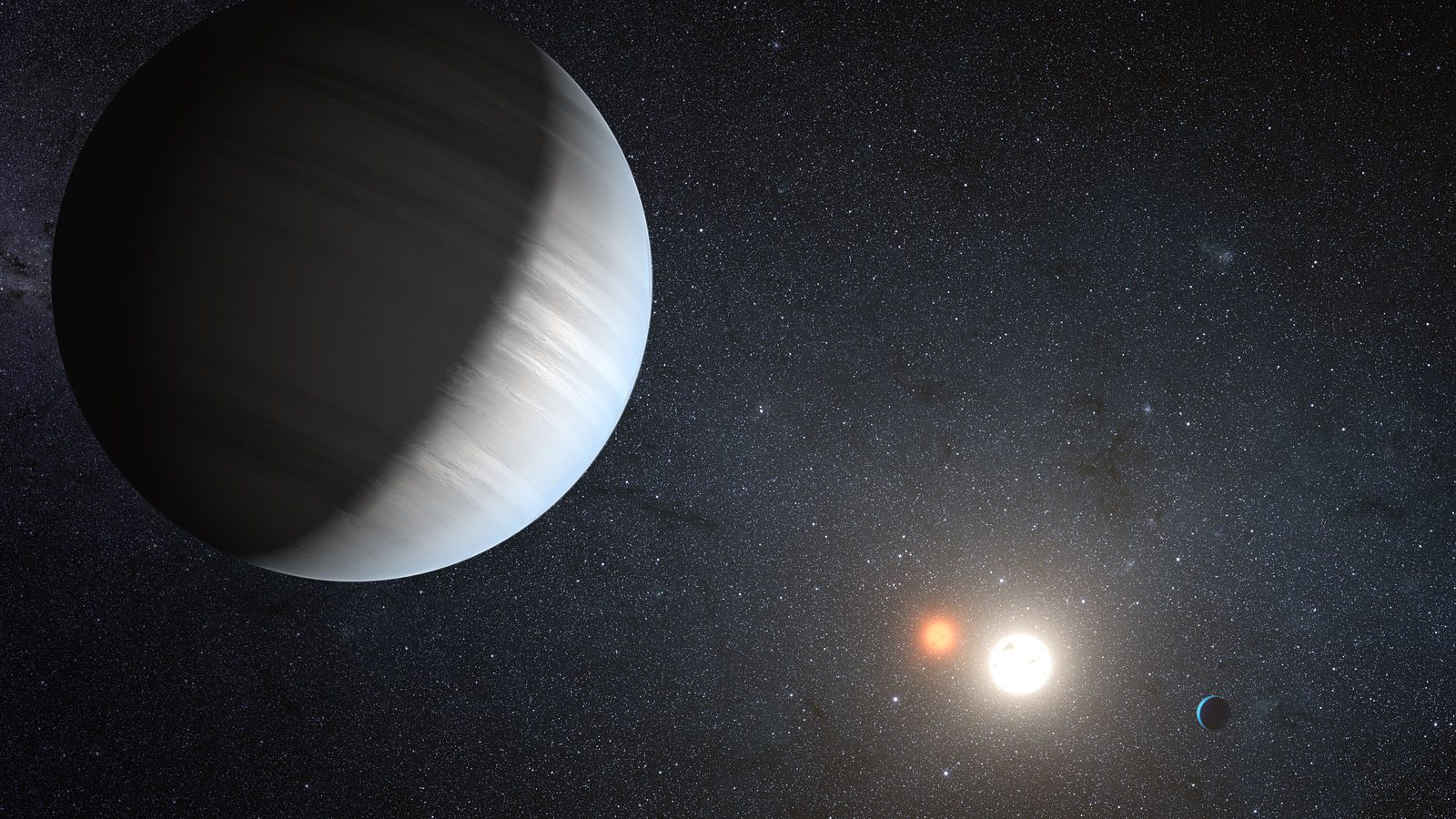

Parreno’s film explores a planet in the Continually Habitable Zone, NASA’s term for an area of a solar system where the existence of life is theoretically possible. Planets within such a zone are far enough from their nearest star to avoid blistering surface temperatures, but close enough to not be permanently frozen. Recent discoveries have shown that such conditions are possible not only for planets that orbit a single sun, but for those with two or even three central stars.

Many such binary stars are red dwarfs, smaller and cooler than our own, which is a yellow dwarf. Our sun’s light appears white to us because it contains wavelengths of all different colors, from red to purple. Scientists think that plants on our planet appear green because bacteria snagged that wavelength early for their own photosynthetic endeavors. Plants then evolved to reflect the green section of the spectrum, and absorb the rest.

A red dwarf, or even two, would provide less light overall, and some researchers have speculated that plants on such planets would evolve to perform “hyperphotosynthesis,” absorbing the entire visible spectrum. Instead of green, they would appear black. For his film, Parreno asked Smets to build a landscape inspired by this kind of alien realism.

After considering a few different land parcels, Smets settled on a private garden in Vila Nova de Famalicao, which had been offered up by its owners, a couple of art collectors who wanted to see what he’d do with it. He then brainstormed and sketched potential extraterrestrial landscape elements—a “burnt hill,” “black plants,” trees with exposed roots—and went about constructing them with materials available on Earth. First, he and his team cleared a patch of land of much of its original vegetation. Then, as the local fire brigade watched, they burned what was left, until the ground itself was a smoked, tarry black.

Next came a streambed, carved sinuously through the middle of the land parcel, and left bone dry. Smets filled this with slabs of black slate, chunks of obsidian, and broken glass. For an intergalactic version of a grassy hill, he terraced a slope and replanted it with black mondo grass, a droopy, deep purple turf plant that grows dark, glossy berries.

He covered other patches of ground with black hollyhocks, orchids, and bugleweed. In the middle of one forested spot, Smets dug a large hollow, and lined it with eucalyptus roots left over from earlier cuttings, as if a massive tree had recently been pulled out of the earth. When the cameras started rolling, Smets’s crew added atmospheric elements—diamond dust blown over the creek bed, and smoke and foam released just above the charred ground.

You’d be hard-pressed to find an existing landscape with these elements. Still, Smets made sure that “the filmic landscape… represent[ed] its own coherent ecology,” says Treib. In the film, with the help of editing, cinematography, lights, and special lenses, viewers see a complete space, almost like an extraterrestrial hiking destination. They’re taken along a glittering “mineral river,” the glass and diamond dust enhanced by floodlights overhead, and given a glimpse up over a black-grassed terrace, where one of two suns rises overhead.

The darkness is disconcerting “only when related to the earth of our own planet,” Treib says. “Can we instead imagine a planet whose territory has always been black… its black stones and crystalline glass the norm rather than the product of some apocalypse?”

These days, the small apocalyptic actions of the film crew are quickly being reversed. “Nature, to a large degree, has had its way” with the site, says Treib, who visited in late 2014. Green plants dot the dry river, shooting up between the chunks of slate. Undergrowth has returned to the eucalyptus forest. The mondo grass, more at home in slightly cooler climates, has largely ceded its space to native vegetation. Despite the landscape’s initial commitment to its role, its star turn is now barely apparent—unless, that is, you know to keep an eye out for the occasional black flower, or to watch for the sun’s rays glinting off broken glass.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook