A Chinese Fishing Village Regains Its Rightful Place in California History

A shipwreck brought Chinese immigrants to the Monterey area. Discrimination forced them to start over.

When Gerry Low-Sabado first visited Whalers Cabin in the 1990s, shortly after it became a cultural history museum, she had no idea that she was a direct descendant of the Chinese fishermen who had built it. Located in Point Lobos, a scenic coastal reserve just south of Monterey, California, the 150-year-old shack held artifacts from the fishing and whaling clans that inhabited the reserve through the turn of the 20th century: first the Chinese, then the Japanese and Portuguese.

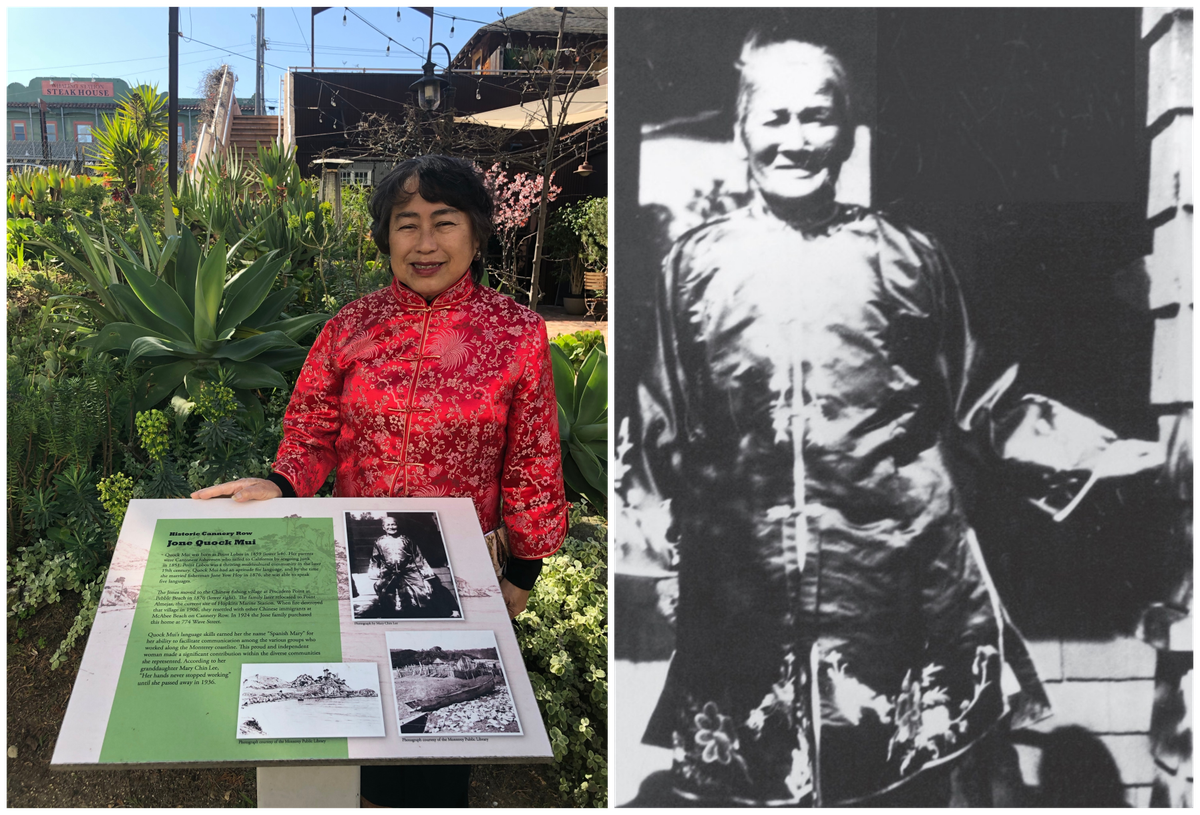

At the time, Low-Sabado was only vaguely familiar with the state’s immigrant fishing history. But a jolt of recognition ran through her when she saw a black-and-white photograph of an elderly Chinese woman. She didn’t know who the woman was, but the house in the background looked like her mother’s childhood home, about 8 miles away in the Cannery Row neighborhood of Monterey. After asking her relatives, Low-Sabado learned that her aunt, Mary Chin Lee, had taken the photo in the 1920s, and that the woman’s name is Quock Mui.

For Low-Sabado and her siblings, the discovery uphended every notion they’d held about their identity. She grew up thinking she was just like white children she knew, and shared their obsession with the Beatles and the Beach Boys. “I couldn’t believe I grew up not knowing who my great-grandparents were,” she says.

Around the same time, the historian Sandy Lydon was interviewing descendants for the second edition of Chinese Gold, his book on 19th-century Chinese history in Monterey Bay. Through the museum, he found Lee and her extended family, including Low-Sabado. Meeting them, he says, changed everything. With their help, he was able to identify old photographs, piece together family lines, and determine that the Quock matriarch was actually the first Chinese girl born in Point Lobos, in 1859. “Mary was our window,” Lydon says. “It’s through her that Gerry rediscovered her roots.”

When Low-Sabado retired after 26 years as a childcare worker, she realized that her newfound family history could give her a new mission. “I felt that I had to try and give a face to their struggles, hopes, and successes,” she says. She launched a campaign, starting in the cabin: Quock’s photo had been misattributed, and Low-Sabado spent years convincing museum and park staff to inscribe her aunt’s name underneath. “That name you see is not just a name,” she says. “That’s five years of my struggle.”

On a recent afternoon in February, Low-Sabado, now 70, walks down a narrow, oak-lined path toward Whalers Cabin. She’s dressed in a traditional red tang suit and a pair of UGG boots. In a small handbag, she’s packed a stack of business cards—a constant companion on her visits to Point Lobos. Her aim is not to promote herself, she says, but to tell the story of California through her ancestors.

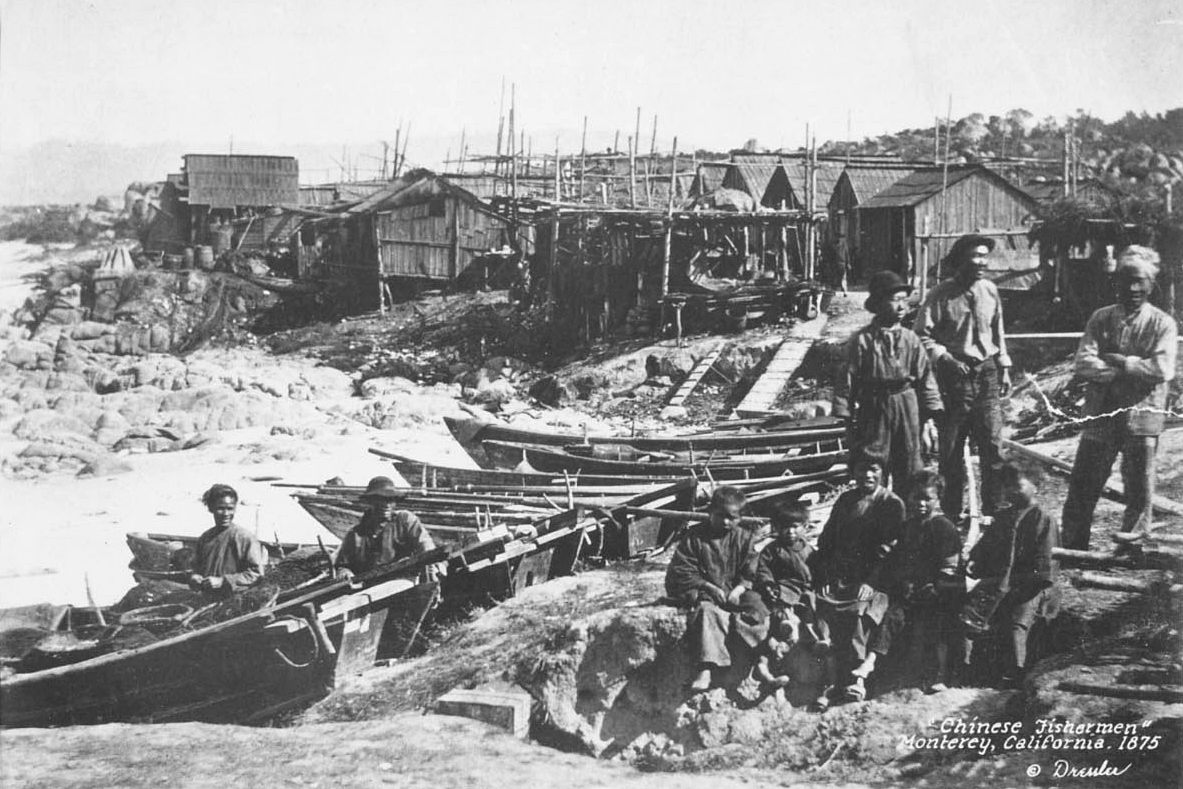

In 1851, a group of indigent Chinese fishermen from the Pearl River Delta were shipwrecked on Whalers Cove, a rocky beach surrounded by low-lying trees. As some of California’s earliest Chinese immigrants, they saw potential in the cove’s rich marine habitats and stayed to establish the first Chinese fishing village in the state.

For Low-Sabado, a fifth-generation descendant of those voyagers, the windswept cypresses and sculptural bluffs of Point Lobos are an ancestral home. Her eyes light up as she sees a couple by the cabin. “You see the photo?” she asks them, pointing at a framed, black-and-white portrait on the wall of an elderly woman. “I’m her great-granddaughter!”

Quock, she tells them with a wide smile, spoke five languages and became the liaison between different ethnic groups, adopting the nickname Spanish Mary. After a 15-minute primer on her great-grandmother’s life, she retrieves a card from her bag and encourages the couple to read more online.

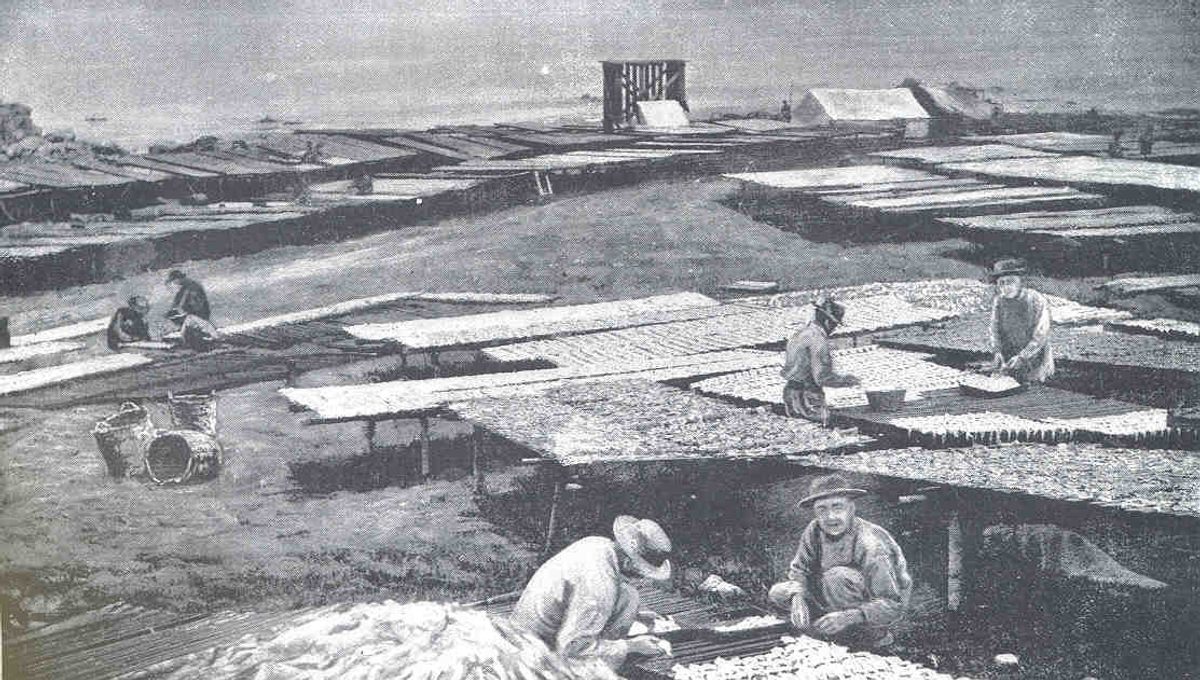

In the 1870s, the Quock clan relocated from Point Lobos to Point Alones, in Pacific Grove—then the largest, most diverse Chinese settlement in the country, with over 500 residents. (Today, it’s occupied by one of Stanford’s research labs, the Hopkins Marine Station.) Point Alones was home to more families than any other Chinatown in California, including San Francisco, according to U.S. Census records. Day and night, clans like the Quocks chased bounties of the Pacific in flat-bottomed Chinese sampan boats. Within 20 years, they developed the state’s commercial fishing industry, annually exporting millions of pounds of abalone, shrimp, and squid.

Quickly, though, their success inspired envy and anger from non-Chinese residents and elected officials, according to Lydon’s research and newspaper accounts. Competitors reportedly cut the nets of Chinese fishermen and barred them from fishing during the day. These local incidents mirrored nationwide trends: In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, blocking immigration by an entire ethnic group. Countless Chinese immigrants, including some with ties to Point Alones, were detained or deported at Angel Island, just a hundred miles north in San Francisco Bay.

Then, in 1906, a suspicious fire decimated the village, driving out its inhabitants and burying their legacy. “Hundreds of spectators cheered the fire as it roared through Chinatown,” Lydon wrote in Chinese Gold. “Many of the white spectators joined in looting. Vandals broke into stores and dwellings not touched by fire and carted contents away.”

Low-Sabado believes that Chinese-American elders kept mum about their roots in part because of the racism they endured. When she was growing up, decades after the incident, her grandparents distanced themselves and their children from their Chinese heritage. “I think they were just afraid,” Low-Sabado says. Some may have feared that they would be sent back to China.

In 2007, Bryn Williams, then a Stanford archaeologist based at the Hopkins Marine Station, invited Low-Sabado and other descendants to excavate the site for remnants of the village. “The history of immigration is an incredibly important part of US history,” Williams says. “The perspectives that descendants like Gerry can bring builds valuable knowledge of the past.” Low-Sabado helped salvage thousands of ceramic shards, a shoe, a mostly intact Chinese teacup, and fish vertebrae. It amazed her that relics of her ancestors’ lives still drifted ashore more than a century after the fire.

During the dig, Low-Sabado discovered that her great-grandfather*, Quock Tuck Lee, was one of the last villagers to leave. In fact, he even tried to rebuild his home before the landowner, the Pacific Improvement Company, forced him out. “It reminded me that my family’s been here longer than people who feel they have a right to discriminate against us,” she says.

Inspired by her great-grandfather, she spent the next seven years persuading city officials and Stanford University to expedite a long-stalled project: a plaque that commemorates the contributions of Point Alones residents. She rallied support from a host of prominent social justice organizations, including the ACLU of Monterey County and the National Coalition Building Institute. In 2014, a plaque was finally unveiled on a boulder near Hopkins, featuring a photograph and short biography of her great-grandfather. “It’s my biggest accomplishment,” she says, without hesitation. Sandy Lydon, the historian, was invited* to the unveiling ceremony, though he did not attend. “Gerry put Point Alones on the map, literally,” he says.

In 1924, 18 years after the fire, the Quock family bought a house on Cannery Row in Monterey, where they lived among Italian sardine handlers. A replica of Spanish Mary’s photograph now hangs in Studio Cafe, a boutique tea and coffee shop that stands there today. (It was once called Quock Mui Tea Room.)

Low-Sabado orders an organic jasmine tea and sits in the courtyard. Taking a sip, she looks pensively around at the place where three generations of her family lived. In raising awareness about their existence, she admits, she sometimes feels a bit like a tattletale. “I’m always wondering, ‘Who am I to tell this story if my ancestors didn’t?’” she says. “It’s a real push-pull for me.”

But a sense of duty outweighs her uncertainty. She and Lydon both describe the accidental discovery of the photograph—and the subsequent connections—as fortunate, even fated. “Some of us believe it’s not just luck,” Lydon says. “We’re being assisted by those ancestors who saw that we got to the right place at the right time.”

The cities of Pacific Grove and Monterey have installed signposts acknowledging its Chinese fishing history. But these markers haven’t created a public consciousness in the way that Chinese contributions to railroads and gold mines have. Recently, some descendants have advocated for more concrete and political ways of restoring their forebears’ legacy.

Nancy Wang, a great-grandniece of Spanish Mary, wrote a play about the fishermen who were shipwrecked at Whalers Cove. She wants to incorporate a version of the story into the city’s elementary school curriculum. “People keep thinking we’re foreigners,” she says. “We need to teach our children that we helped build this country.”

Russell Jeong, a fifth-generation descendant and an Asian American Studies professor at San Francisco State University, says that institutions need to be held responsible—starting with his alma mater, Stanford, which built Hopkins atop his family’s demolished home. “I want Stanford to apologize for its record of discrimination,” he says. “I want Stanford students to recognize that their privilege is built on the labor and land of people of color.”

Low-Sabado, for her part, is focused on planning her 11th Walk of Remembrance, an annual commemorative march to the Point Alones village. At her age, she says, she needs to pick her battles, whether that means handing out business cards to strangers or sharing her story to students around the Bay Area. “Sometimes, it’s another young generation that will pick up my cause,” she says.

* Correction: An earlier version of this story identified Quock Tuck Lee as the grandfather of Gerry Low-Sabado. He was her great-grandfather. It also stated that Sandy Lydon attended a 2014 unveiling ceremony. He was invited to the ceremony but did not attend.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook