The Chef Recreating 18th-Century Recipes From a Thrift-Shop Find

Bake an old-timey cake from this handwritten cookbook.

Lucinda Ganderton had the book hidden in the bottom of her shopping trolley. Around two years ago, she had taken a trip from London to Brighton, England, to visit Paul Couchman, a food historian and chef whom she met on Instagram. Ganderton, a textile artist whose family had once owned an antiques auction house, and Couchman, who specializes in 1830s British cookery, connected over a shared love of antique kitchenware. Ganderton was clearing out her house when she found a few objects she thought might spark Couchman’s interest.

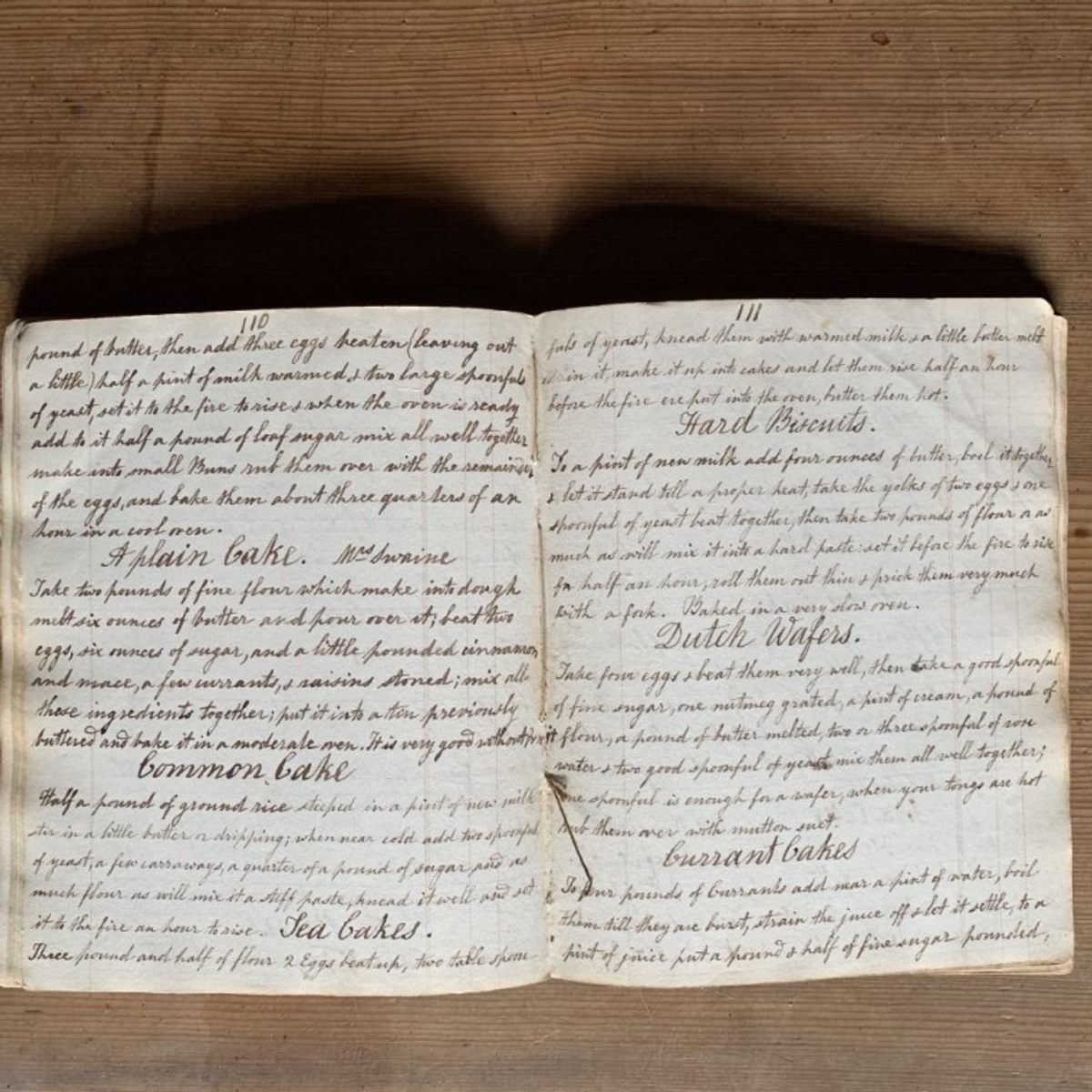

“First time I went down, I took this massive great bag with the jelly moulds,” she says. “I hadn’t told him about the book. I was like, ‘By the way I’ve got this.’ And his face just lit up.” The “this” in question was covered in weatherbeaten leather, its binding grayish and nondescript. But inside was a treasure trove of more than 150 yellowing, rag-paper pages containing dozens of recipes for everything from catsup to plague cures, written out painstakingly in a few different people’s handwriting.

The compilers hadn’t signed their names or specified the book’s place of origin, but they did date some of the entries: one compiler noted 1780; another, in tiny letters on the back inner binding, wrote that the book was finished in 1831. (From the book’s use of rag paper, rather than wood pulp, Couchman could confirm that it dated to before the 1840s.) Ganderton had purchased the book a year before, for 40 pounds in an Oxfam thrift shop. “It was wrapped up in a plastic bag with a label on it that said ‘very old cookery book,’” says Ganderton. “Fair enough. That’s what it was.”

“It’s a mystery, this book. We don’t really know much about it,” says Couchman, radiating enthusiasm. “That makes it more intriguing.”

Couchman, who goes by the name “The Regency Chef,” offers historical dinners and cooking classes out of The Regency Town House, a restored 1820s mansion in Brighton, England. Even before finding the manuscript, he’d been working with recipes from the early 1800s in an attempt to recreate an authentic sensory experience in the home. But he’d mostly worked from modern editions of antique printed cookbooks, or originals he consulted in rare-books libraries.

In contrast, the manuscript offers an intimate portrait of daily life and daily bread from an era when even manuscript cookbooks were still largely confined to the households of the elite. Couchman has already shared recipes from the book on his website and in his online cooking classes. Now he’s raising money to preserve the book, which is literally spineless and at risk of deteriorating from years spent in humid kitchens.

Much like the book, Couchman reached the Regency Town House by chance. He spent the first decade of his adult life as an artist in Amsterdam. When he moved back to England, he stumbled onto the restoration project, which curator Nick Tyson had been leading since the 1980s.

The town house’s name refers to a time period, the Regency, that spans the first couple decades of the 1800s. Politically, it marks the time when King George IV ruled in proxy for an ailing King George III, the monarch against whom American colonists had fought the Revolutionary War. Culturally, it’s defined by opulent artistic, architectural, and culinary styles that incorporate influences from the U.K.’s growing colonial exploitation of Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, as well as the Renaissance and vernacular English art. Brighton was a center of Regency architecture, as evidenced in its famous domed Royal Pavilion.

Tyson aims to make the Town House a physical, sensory escape into the era, rather than just a museum. “We would be able to build a better, stronger, richer picture of Brighton 180 years ago than we otherwise would have,” he says of his decision to lead the restoration. The building itself reflects both the colonial brutality and stylistic gentility of the era: At one point, one of its occupants was head of the East India Company.

Volunteers helped restore an old-fashioned dresser for kitchenware and a “scullery,” or washing-up room. When kitchen restoration was finished, there was one thing missing: a chef. “So one Christmas I started making mince pies,” says Couchman.

The tradition stuck, and Couchman found himself learning how to recreate historical recipes. He has worked on a series of cooking courses and pop-up dinner fundraisers in the town house, where he uses a mix of modern and antique implements to serve guests period-era dishes. Many of the dinners examine the class stratification of English aristocratic households, seating guests in the kitchen and feeding them fare that would have historically been reserved for domestic workers. “I called them ‘Dine like a servant’” events, says Couchman, whose grandparents had worked “in service” within England’s historically rigid class system.

The recipes in the 1830s manuscript, however, are far from humble fare. The book contains recipes—or “receipts,” in the archaic spelling—for salted meats, soups, cheeses, pickles, catsups, puddings, pastries, and sweets, as well as for medicines and household concoctions. Recipes for cakes and pastries, which required sophisticated ovens and expensive spices, indicate the book was used in a wealthy household. So, too, do the recipe quantities, which regularly call for dozens of eggs and pounds of flour, indicating cooking for special occasions.

Manuscript cookbooks such as Couchman’s—that is, cookbooks written out by hand—were usually kept by the lady of an elite household, says Stephen Schmidt, a specialist in manuscript cookbooks. He’s the principal researcher and writer with the Manuscripts Cookbooks Survey, which is building a bibliography of all such pre-1865 American and British works held in the United States. He says most of the surviving manuscript cookbooks are difficult to access, either held with restricted use or without proper cataloguing in libraries and museums, or the property of private collectors. That’s part of why Ganderton’s find was so unexpected.

The manuscripts that do remain reflect the gender and class dynamics of historic households. “Through the mid-19th century, the compilers of these books tended to be fairly privileged, and the reason was that fairly privileged people from the upper-middle class and beyond cooked according to the fashions,” says Schmidt. “Everyone else cooked what their mothers taught them.”

By the 1830s, the lady of an elite British household would likely have been literate. She would have copied receipts from other ladies, occasionally from servants, and from printed cookbooks, often while adding her own notes. Couchman’s manuscript, for example, has a Stilton cheese recipe, which he traced back to a printed Scottish cookbook. The original version uses marigolds for yellow color; the author of Couchman’s manuscript noted that they preferred it without the flowers. The lady of the house wouldn’t have cooked herself, but she may have read the recipes in the book out loud as workers prepared the dishes and made notes about how the recipe turned out. This distance from the actual act of cooking explains the book’s relative lack of food stains.

Other recipes in the manuscript show the playful connection between oral and written cultures. A rhyming recipe for “Mother Eve’s pudding”—a popular bread pudding made with apples and named after the Biblical apple-eater—appears in nursery-style verse. “Oftentimes in recipes they would do them in verses so people could remember them, because they couldn’t read or write,” Couchman says.

Also typical of the time is the manuscript’s mingling of medicinal and culinary recipes. Recipes for curing hams, pickling salmon, and salting tongue mingle with plague cures. “There’s a remedy for toothache, whooping cough, worms,” says Couchman. “Stoppage in the bowels— that’s lovely, isn’t it?” Sometimes it’s hard to distinguish between the medicinal and the culinary, as with a recipe for wine jelly, which the author notes is meant to fortify “weak people.”

While the book is unsigned, bits of the authors’ personalities shine through. An inscription at the beginning, for example, is a somewhat dour reminder to be industrious. “In 40 years, the difference between rising at 6 o’clock instead of eight, supposing the person go to bed at the same time he otherwise would, amounts to 49,000 hours or three years, 121 days and six hours,” the author wrote. (The writer’s math is wrong—it would actually be 29,200 hours—but their jibe at late risers is well taken.)

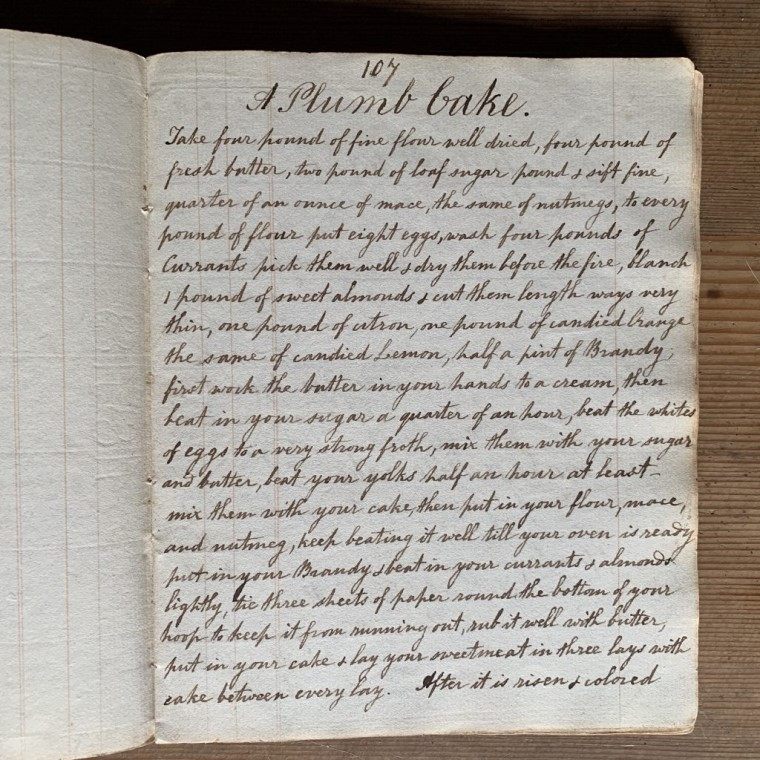

When I talk to Couchman around the winter holidays, his kitchen is rich with suet and spice. He teaches an online course on how to make a traditional English boiled pudding, studded with dried fruit and boiled in a bag; he’s also incorporated the manuscript’s plumb cake and lemon mince pies into his holiday line-up. These recipes are the clear antecedents of traditional English Christmas fare, sharp with candied citrus and liquor, and dense with suet or butter and nuts. The citrus would have come from Italy and Portugal, while the spices and sugar would have come from Britain’s colonial exploitation in the Caribbean and South Asia. Meanwhile, the recipe for piccalilli, a brine-based pickle, is an anglicized imagining of a South Asian pickle, featuring fruit, cucumber, and shallots preserved in ginger, garlic, turmeric, sugar, salt, and white wine.

Not every recipe in the book is pleasing to the modern palate. “I tried one. It was absolutely disgusting,” laughs Ganderton. “It was a chestnut flan, and I don’t think it had any sugar in it.” But if anyone can make 200-year-old fare appealing, she says, it’s Couchman. “He just inspires people,” she says. Couchman, for his part, says that while the piccalilli might be tasty, giving life to the long-forgotten recipes comes with its own relish. “I love showing bits of the book,” he says. “I’ve got it, but it’s meant to be shared.”

A Plumb Cake

Interpreted by Gastro Obscura, based on Paul Couchman’s adaptation of the recipe in his 1830s manuscript cookbook. The cake has a nice, slightly crunchy exterior and a rich, almost pudding-like interior.

For cake

3 cups of flour

2 cups of butter

1 1/4 cups sugar

1/2 teaspoon ground mace

1/2 teaspoon ground nutmeg

6 eggs

2 ¾ cups currants

1 cup flaked almonds

1/2 cup candied grapefruit*

1/2 cup of candied lemon, finely chopped. You can buy them pre-candied or candy your own.

1/2 cup of candied orange, finely chopped. You can buy them pre-candied, or candy your own.

¼ cup brandy

*The original recipe calls for citrons, a lumpy, sharp citrus fruit from which many other citrus fruits were bred. They have a thick rind, and English chefs traditionally candied them for use in desserts. They’re difficult to find in American supermarkets, so I used candied grapefruit to replicate the sharp fruitiness. (English colonizers in Barbados first described grapefruit in 1750; they called it the “forbidden fruit of Barbados.”)

For topping (optional)

Around 10 intact slices of candied lemon, orange, and/or grapefruit, for garnish (optional)

¼ cup butter

½ cup brown sugar, loosely packed

- Preheat the oven to 325 degrees. Grease a seven-inch round cake pan.

- Beat the butter and sugar together until they are light and creamy. Since there isn’t any baking powder in the cake (baking powder wasn’t invented yet), the recipe relies on fluffy butter and beaten egg whites to rise.

- Separate the eggs. Beat the egg whites until they form stiff peaks. In a separate bowl, beat the yolks until they are light and frothy. Use an electric mixer to speed the process up, or beat them by hand for authenticity (and a stellar arm workout).

- Add the beaten egg yolks into the butter and sugar mixture, stirring continuously. If the mixture begins to curdle, add a tablespoon of flour and continue mixing until you’ve incorporated the egg yolk.

- Gently stir the flour, mace, and nutmeg into the egg mixture until incorporated.

Combine the dry ingredients with the butter and sugar. Reina Gattuso for Gastro Obscura - Stir in the currants, brandy, and flaked almonds, still gently.

- Fold the beaten egg whites. Don’t over mix, as this will knock out the air you need to make the cake rise. The batter will be thick; that’s okay.

- It’s not in the original recipe, but if you’d like to create a lovely pattern on the top of your cake, cut up three tablespoons of butter into pea-sized pieces and sprinkle evenly across the bottom of the pan. Spread half a cup of loosely packed brown sugar across the pan with the butter. Then line the bottom of the pan with a layer of candied fruit slices.

- Pour the first half of the batter into the pan. Then cover it with an even layer of chopped candied lemon, orange, and grapefruit.

- Pour the remainder of the batter over the candied fruit. You may have to spread it with a spatula to make sure the batter is even.

The cake should be a rich brown on top. Reina Gattuso for Gastro Obscura - Let the cake bake until a knife inserted in the center comes out clean. This may take an hour and a half to two hours depending on your oven. The top will be a medium-dark brown color and the cake will smell slightly toasty.

- Remove the cake and leave it to cool before you turn it out of the tin. To turn out the cake, hold a plate on top of the tin with two hands; flip holding the tin and cake together. If you chose to add a topping to the bottom of the pan, you should have a lovely pattern of caramelized candied fruit on top.

The outside of the plumb cake is slightly crisp, the inside is dense and fragrant. Reina Gattuso for Gastro Obscura

*Correction: Due to a misreading of historic script, an earlier version of this article incorrectly titled the recipe “Plumb Bake” instead of “Plumb Cake.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook