Hand-Drawn Maps That Jump Into the Geopolitical Fray

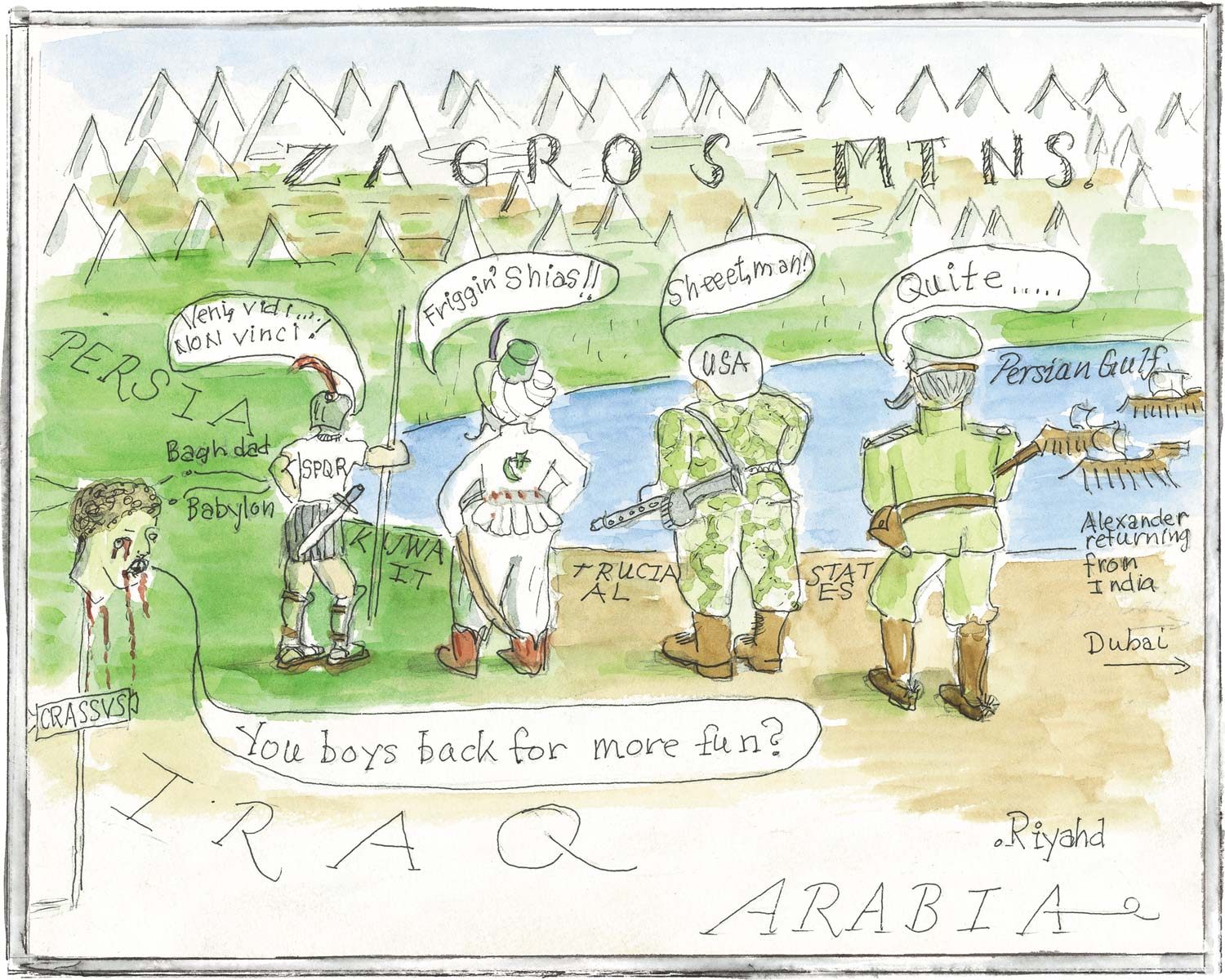

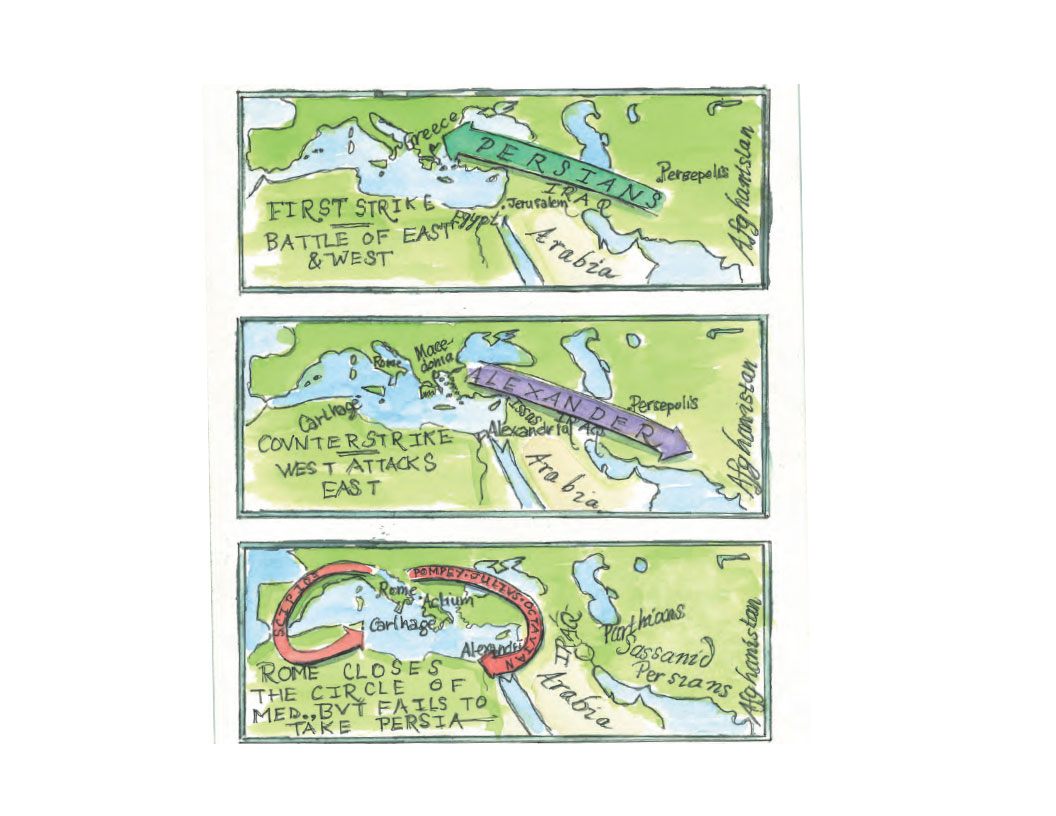

One of Danforth’s cartoons, which shows different groups through history who all fought in Iraq. (Image: Ted Danforth)

What better way to understand and explain geopolitics than through maps?

The Eastern Question, a new book filled with hand-sketched maps and cartoons about history and international relations, rests upon the idea that both are woven of repeating patterns, and that no war is an isolated event.

The book’s author is Ted Danforth, a letterpress “scholar-printer” whose deep appreciation for political history and the written word is evident in the highly detailed and ambitious production. Danforth, looking through a geopolitical lens, tries to capture three millennia of human history with the help of 108 maps, drawings, and political cartoons.

“As the West declines relatively and the East rises, seemingly new questions are asked that are in fact old ones. The current conflicts in the Middle East are present-day manifestations of geopolitical dynamics that have been active in the historical process from the beginning,” writes Danforth. (Image: Ted Danforth)

Danforth’s idea for the book was spurred by the attacks of September 11, 2001. As subsequent events unfolded, “I saw that what might seem to be the multitudinous and arbitrary events of history…are manifestations of dynamics that go back to the beginning of recorded time,” he writes. Danforth spent the next 14 years “reading, thinking, positing things, organizing things, then trying to figure out what is going on here,” he says.

The book’s title, “eastern question” comes from a 19th century term that alluded to the inevitable fall of the Ottoman Empire, a collapse whose repercussions are still being felt today. The sketches are relatively simple, but they aim to portray complex concepts that set the course of history.

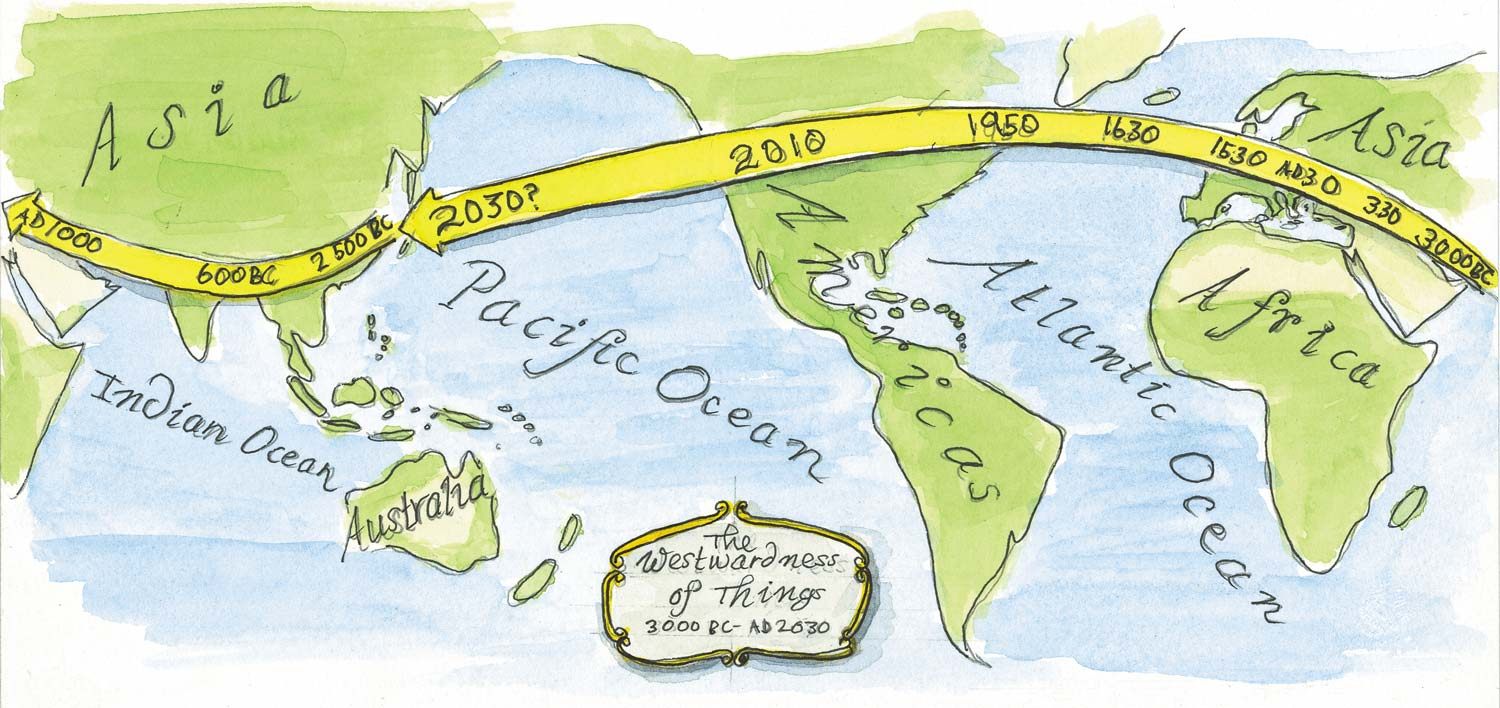

A map that paints a picture of areas that are “desert” and others that are “sown.” (Image: Ted Danforth)

The above map of “Desert & Sown” illustrates the world’s prime agricultural regions, determined by earth’s climatology. With European conquest of the world, Danforth explains, areas of greater agricultural strength conquered weaker ones. There is now a reverse trend of migration from the desert to more cultivated regions, and as more and more people today move across borders, the desert is enfolded within greener landscapes. The “non-integrating gap” is the band of deserts and mountains that cut the world in half, dividing the “Known World of the ancients”–the Greeks and Romans–from Africa, India, and China. The Silk Road ran through this gap, linking these two “world systems,” controlled by the Persians, then Turks, Mongols, and finally the Ottomans.

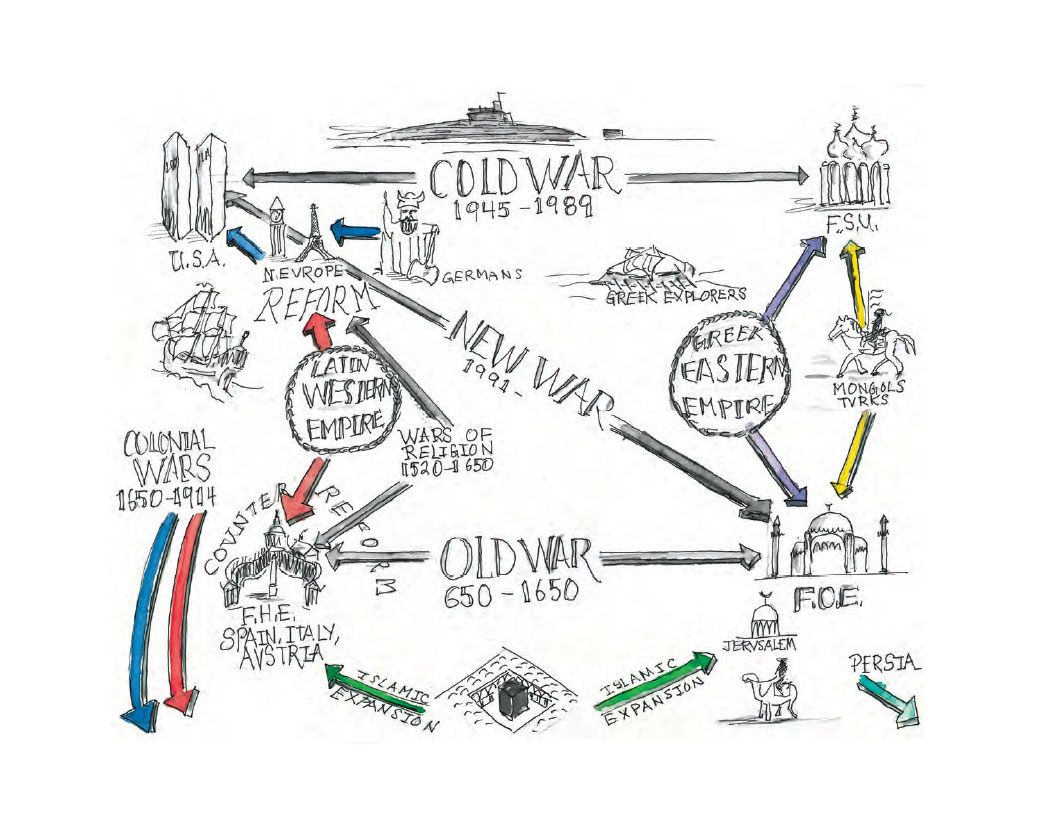

The book features six major players: the Mongol (later Russian) Empire, the Catholic Latin West, the Eastern Empire, the Northern Europeans, the Shia Persians, and the Sunnis. The perspective is distinctly Western, though. For example, the East is described as being “where the trouble comes from.” (Danforth points out that you couldn’t say that trouble comes from the east if you’re in the east; for the West, “trouble” refers to steady streams of Eastern invaders such as the Mongols and Turks.)

Places like South America, Africa, and most of Asia remain silent and on the periphery of history–a result, Danforth says, of having to limit the scope of the project. That said, he thinks it would be interesting to approach the same concept from a different lens, a place where the North, or South, or West is instead where ”trouble comes from.”

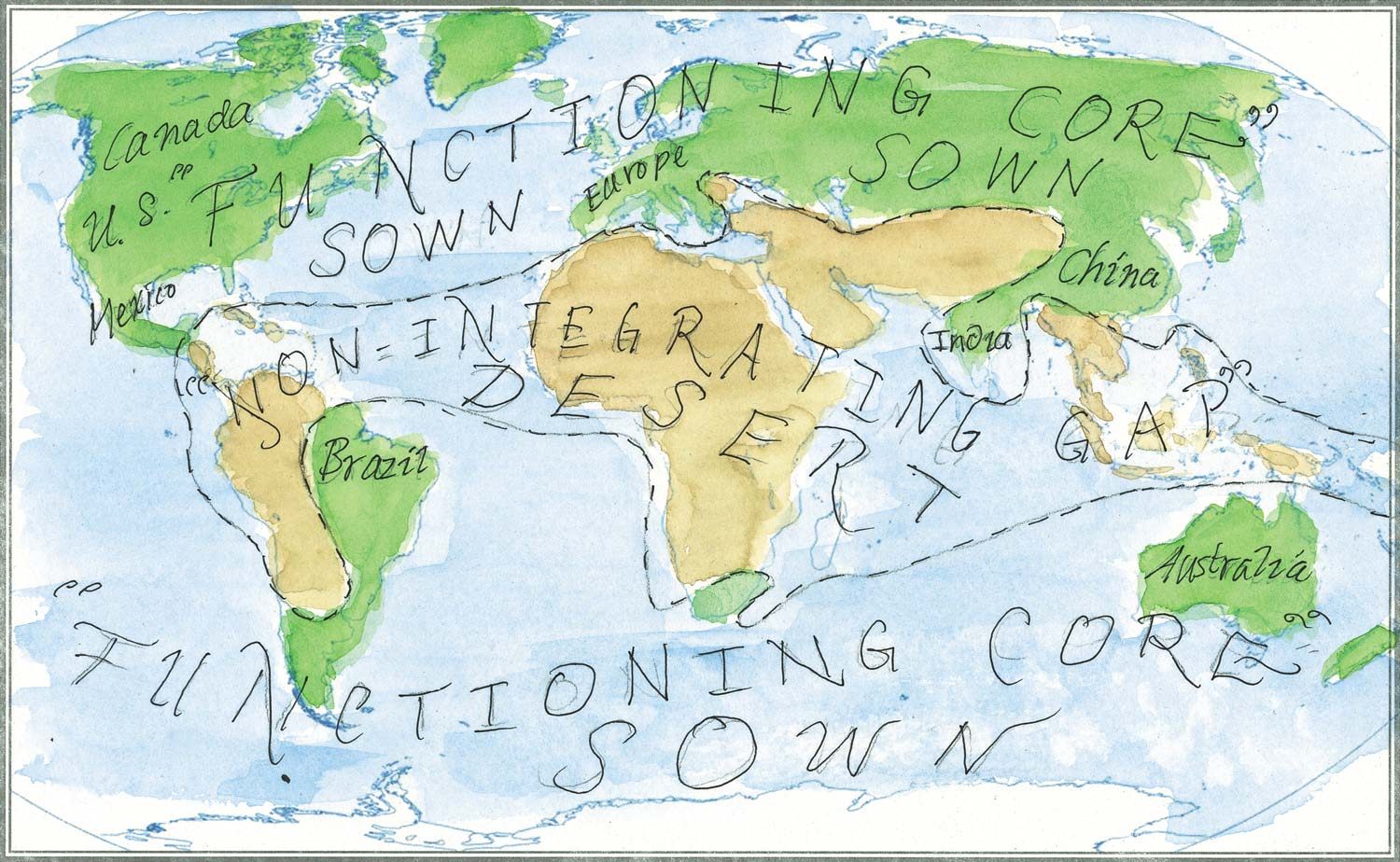

A flow chart of sorts illustrating relationships between different wars. (Image: Ted Danforth)

The Eastern Question is not exactly casual bedtime reading. Danforth throws around a lot of big words and even bigger concepts: democracy, tyranny, freedom, stability, chaos, boundaries, failed states. Properly understanding the inseparability of history and geography through all of these maps requires mental energy and an alert mind.

Danforth, however, says that people should read and flip through the book quickly. “It’s meant to give people a framework for their own knowledge or future knowledge,” he says. He’s really trying to provide a big view of the world, world history, and the larger dynamics that have been active from early on.

History and geopolitics: There is a lot going on. (Image: Ted Danforth)

As for predicting the future, Danforth says he tries to avoid that. “How reliable are the predictions of meteorologists? I’m trying to look at these dynamics as natural phenomena.” Weather forecasts are never guaranteed, but they do anticipate certain patterns.

History, politics, warfare—it all reduces down to an eternal, atlas-proven truth: Location is everything.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook