Sold: An 1891 Patent by Granville T. Woods, Innovative Black Engineer

Woods was prolific, but was largely forgotten for many years after his death.

Had Granville T. Woods been allowed to focus on his work—and pay less attention to lawsuits—who knows how many more inventions he’d have to his name?

The Black American inventor, born in Ohio in 1856, secured more than 60 patents before he died in 1910, at the age of 53. His output ranged from egg incubators to enhancements for telephones and phonographs, though he is now best known for his work on railway systems and transportation safety. In 2004, during the New York City Subway’s centennial year, commemorative MetroCards stated that Woods “made subway travel possible in New York City when he patented the third-rail system for conducting electric power to railway cars.” The National Inventors Hall of Fame cites the third rail as one of Woods’s greatest achievements, along with the induction telegraph, which enabled moving trains to communicate with stations and prevent crashes.

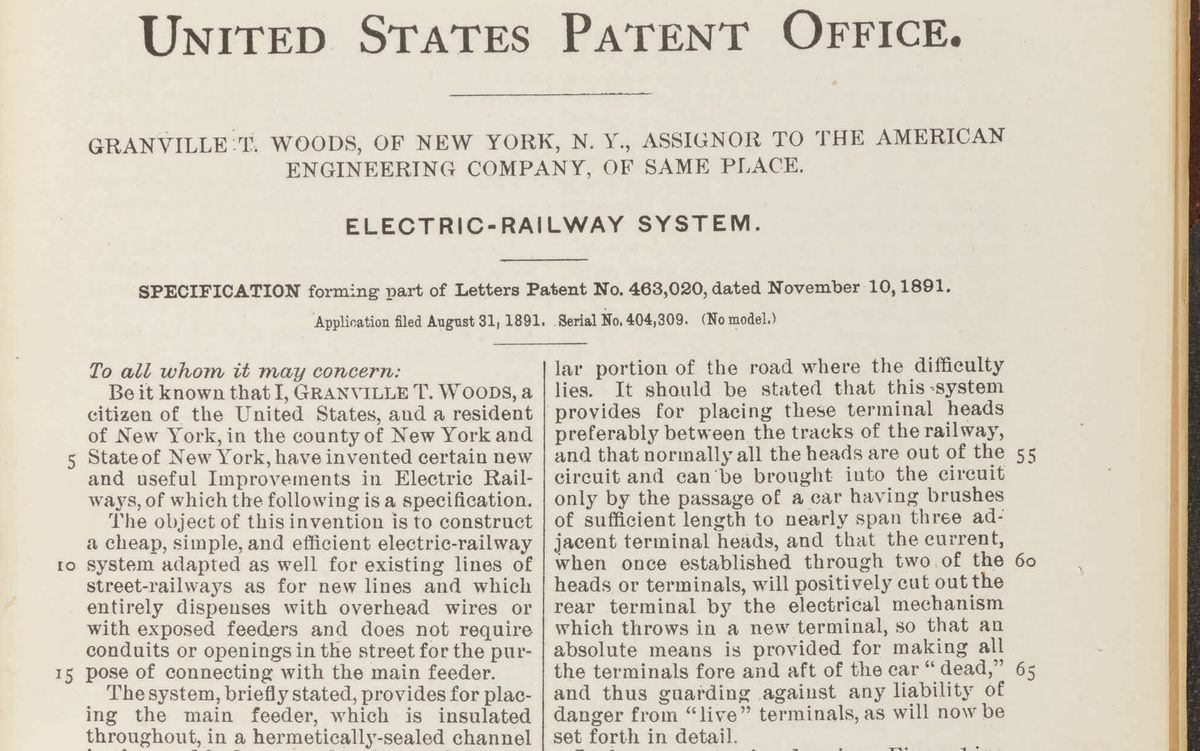

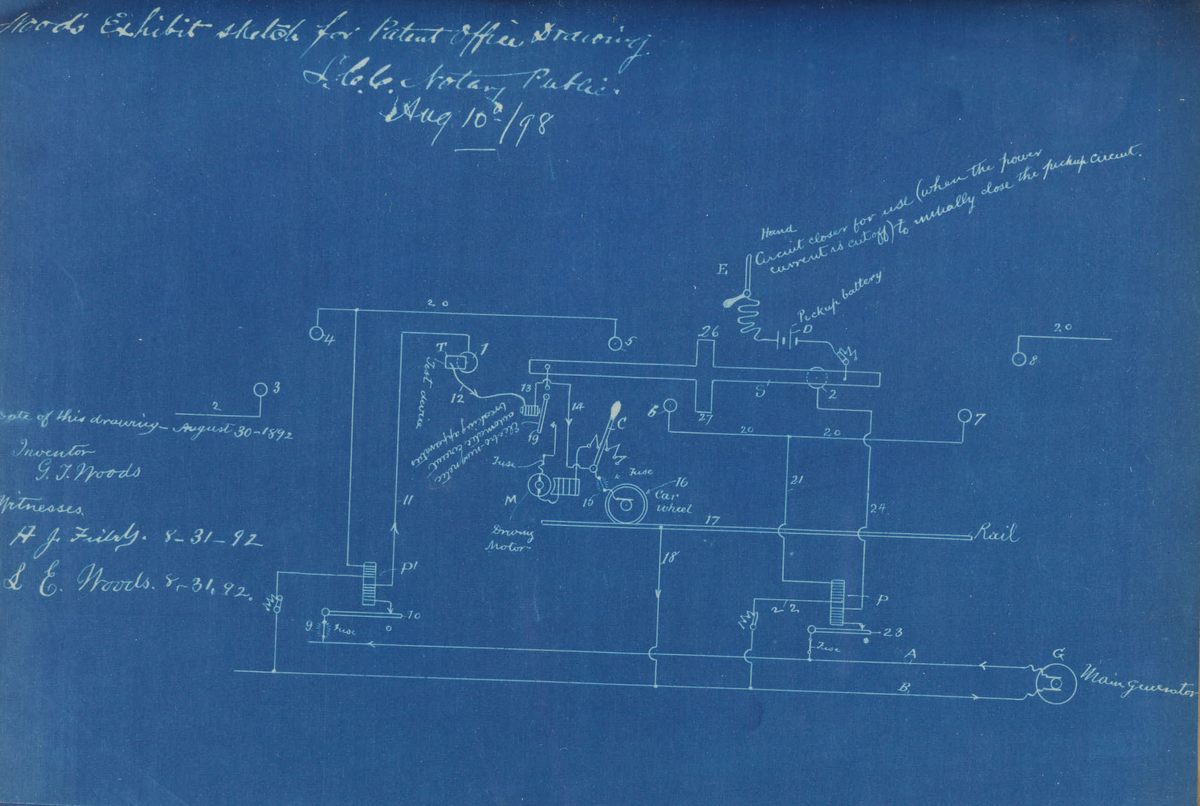

On July 21, 2020, one of Woods’s original patents was sold in Sotheby’s Fine Books and Manuscripts auction, for $3,500. It outlines Woods’s development of an electrical line that is entirely concealed underground—or, as Woods described it in the 1891 patent, “a cheap, simple, and efficient electric-railway system … which entirely dispenses with overhead wires or with exposed feeders and does not require conduits or openings in the street …” The patent was sold alongside other papers from Woods’s life and work, including a blueprint and sketches for another of his many creations. Justin Caldwell, Vice President of Sotheby’s New York, says he’s not aware of any other auctions that have included Woods’s work or papers.

Despite his striking productivity, Woods had a difficult time profiting from his inventions. Rayvon Fouché, a professor of American Studies at Purdue University who studies technology and invention, says it’s a common misunderstanding that patents lead to wealth. More often, competition with other inventors—or a simple lack of commercial interest in the product—prevents innovators from seeing major returns, says Fouché, who is also the author of Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson.

Certainly, Woods faced a great deal of competition, sometimes from the very top of the inventor’s world. In fact, Thomas Edison sued him twice (unsuccessfully, both times). Woods was working in a time of rapid and meaningful innovation in the field of electrical engineering, when it was not uncommon for inventors to quickly license their creations and then move on to their next projects. But Woods was also burdened with some particularly duplicitous collaborators and poorly timed lawsuits. He endured nasty legal proceedings against his business partner, James S. Zerbe, over claims for designs related to electrical locomotion, and fought Zerbe in court for close to a decade. Woods prevailed, says Fouché, but “the moment passed,” he explains, and the patented technology was no longer in vogue by the time the suit wrapped up. (The lots sold by Sotheby’s also include legal documents pertaining to the dispute.)

Beginning during Woods’s lifetime, trade publications and other newspapers took to calling Woods the “Black Edison,” a nickname that reflected the virtual absence of Black Americans in engineering during Reconstruction and the late 19th century. That reality haunted Woods, who, according to a recent belated obituary in The New York Times, often said that he was born in Australia in order to distance himself from the strictures of America’s racial hierarchy. Though Woods found (relatively) more financial success later in life, after selling a series of inventions to the likes of General Electric and George Westinghouse—including an early version of the “dead man’s brake,” which can stop a train with an incapacitated conductor—he was still deprived of the recognition that others in his field enjoyed. In fact, despite working at the top of his field, alongside figures such as Westinghouse, Woods was buried in an unmarked grave in Queens, which only received a stone in 1975.

His life is a lesson not only in science and innovation, but also in the precariousness of legacy. Inventors, says Fouché—both those who enjoy credit and those who are denied it—rarely innovate in isolation. Many brilliant minds work simultaneously on the same problem, and for reasons of prejudice, luck, or law, just a few of them enter the historical record.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook