How a Coffee Blend Defined an Era of Israeli Politics

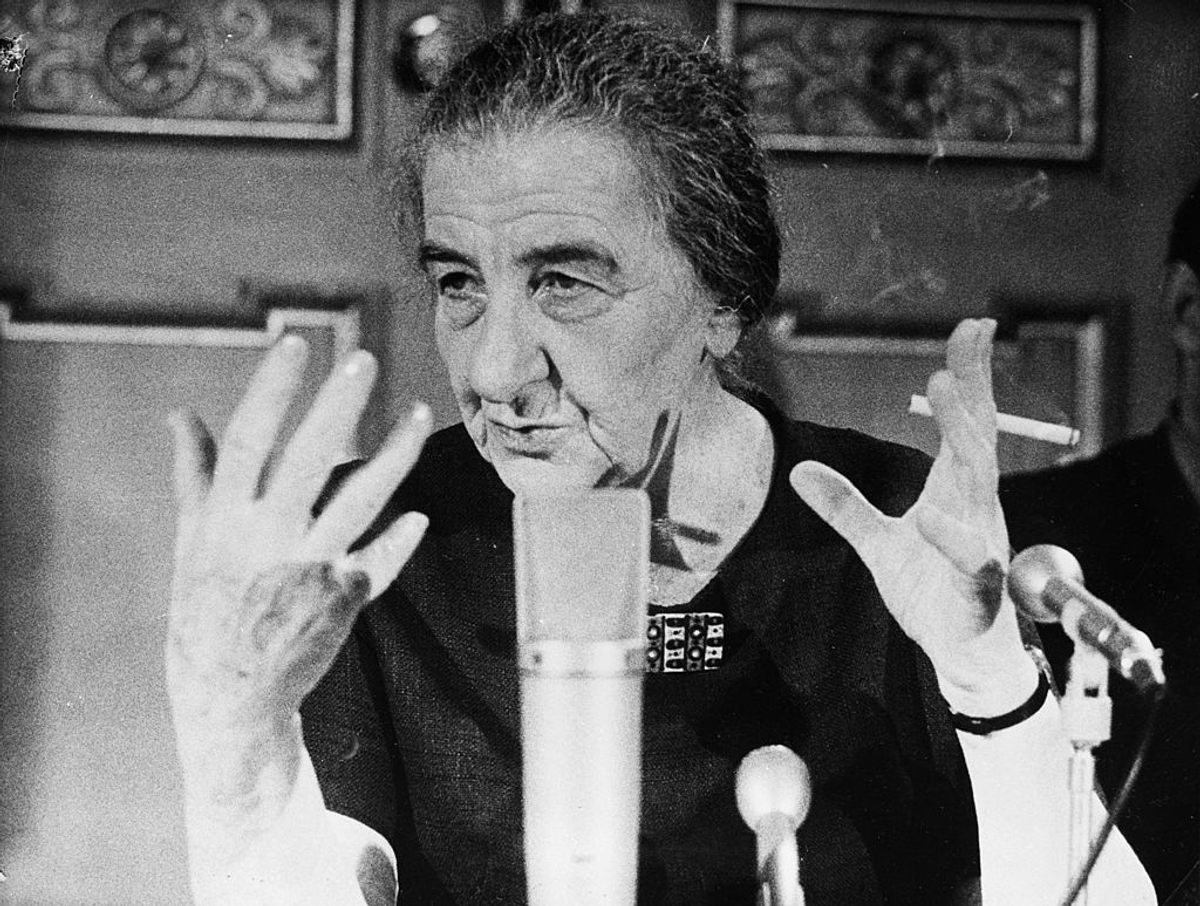

Israel’s only female prime minister favored a potent roast that carries her name.

Aaron and Mura Cohen once roasted and sold many coffee blends in their now-shuttered shop. But when they retired, a little over a decade ago, there was one recipe they couldn’t let disappear. For years they’d custom-made it for a local of their north Tel Aviv neighborhood, a loyal customer whose kitchen was, for a time, an Israeli political headquarters. Now named after this bygone regular, the couple sought someone to carry on their proprietary method for roasting coffee à la Golda Meir—Israel’s first, and to date, only female prime minister.

“They used to make her the coffee blend that she liked,” explains Uri Rafaelli, whose family has owned and run the Atlas Coffee shop in Tel Aviv’s Levinsky Market for 45 years. “After [Aaron and Mura] didn’t have energy to roast, we would roast it for them. And after they didn’t have energy to sell it either, and closed their shop completely, they gave us permission to sell it and use the Golda name.”

Meir’s coffee was more than the average morning pick-me-up. According to her biographer, Elinor Burkett, “drinking coffee in Golda’s kitchen [remained] an Israeli political institution.” From the time Meir served as a cabinet minister in the 1950s and throughout her five-year term as prime minister from 1969 to 1974, an inner circle often huddled in her green Formica kitchen to talk policy—likely over a cup of black coffee. Meir’s favorite brew was sipped by heads of state, decision makers, and foreign dignitaries.

“It’s a very strong coffee,” Rafaelli describes. “Bitter, and it has a bit of a special aroma.” He hesitates to add that the blend’s acidity recalls the blunt personality of its famous drinker, as well as her reputation as an Iron Lady.

As prime minister, when Meir was frustrated that her cabinet couldn’t accomplish anything during meetings on Sundays (the first day of the Israeli work week), she started her own weekly tradition. A select group dubbed Golda’s “Kitchen Cabinet” gathered around the countertops of her Tel Aviv home at 8 HaBaron Hirsch Street on Saturday evenings to make important decisions in advance. “It was a mark of honor to be invited to meetings in Golda’s kitchen,” veteran politician Lova Eliav told food journalist Ofer Vardi. “It showed that you were important.”

But not everyone was pleased with this arrangement. Those uninvited to Meir’s kitchen felt out of the loop come Sunday morning. “We demand to be fully involved at all levels, including Golda’s Kitchen Cabinet,” protested members of the opposing party in a 1972 meeting. Meir’s response? “There is a limit to the number of people my kitchen will hold.”

Meir’s kitchen was roomier during the rest of the week. She started her grueling days there alone, with a 7 a.m. breakfast of coffee, toast, and hard-boiled eggs. Her morning cup was the first of an alleged dozen coffees she drank daily while acting as prime minister, a habit fueled by the two kettles constantly brewing on her stovetop.

“For me the recurrent picture from those days is of Golda hunched over the kitchen table, forever stacked with heaps of papers: files, budgets and construction plans, reports, drafts of the National Insurance Law she saw through the [Israeli Parliament] and successions of documents of all sorts and shapes, all neatly arranged,” recalled her son, Menahem Meir, in his memoir about his mother. “Reading glasses perched on her nose, ashtray overflowing and a fresh pack of cigarettes at the ready, a cup of coffee forgotten and cooling at arm’s reach.”

Meir was a notorious chain smoker, known for burning through three packs of no-filter Chesterfields every day. That was partly just her habit, but also surely a way to cope with the stressful events that took place during her term. She was prime minister during the Munich massacre, when Israeli athletes were taken hostage and killed during the 1972 Munich Olympics, as well as during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. A diet of nicotine and caffeine helped her get through those episodes.

With time, questions have been raised about the appropriateness of identifying Israel’s only woman prime minister with her quaint kitchen quarters. Linking her with the matronly tasks of cooking and serving may have been a way to knock this female politician down a peg in the male-dominated realm of Israeli politics. “At the end of the day—even with all of her political life and her important and central role as prime minister—they still associated her with the kitchen,” says Vardi, who researched Meir as part of his weekly column about Israeli leaders and their food habits.

“I’m not sure if that term, Kitchen Cabinet, would ever be applied to a male politician,” Vardi adds. “Today it wouldn’t be politically correct. I don’t think that today, for example, somebody would link Merkel in Germany with her kitchen. Or Hillary Clinton, or women leaders in general. Margaret Thatcher wasn’t connected with her kitchen. It was just a different time, for better and for worse.”

Meir’s famous kitchen, the one where the Saturday evening meetings took place, was in a modest duplex home that she shared with her son in north Tel Aviv. A nearby park is named Golda’s Garden, and a plaque notes that Meir lived there from 1959 to 1978, a period that encompasses her term as prime minister plus the few years before her death.

The Jerusalem home where she lived during the week, while acting as prime minister, was used by three heads of state including herself. It opened a few years ago as a museum devoted to Levi Eshkol, who preceded Meir as prime minister. The kitchen at the museum was restored to look period-appropriate, but isn’t a precise reproduction of how it looked when Meir resided there.

“This really isn’t the original kitchen and isn’t even an exact replica of it, so it’s hard to say that this is Golda’s kitchen,” explains Shavit Ben Arie, director of the Levi Eshkol Museum and author of a book about female members of Israeli parliament. “Golda doesn’t actually have any center or place that commemorates her, to date.” In fact, in Meir’s own will requested that no monuments be erected in her honor after her death.

Thus, despite lobbying by some of Meir’s descendants, there is currently no museum, library, or even politically incorrect kitchen commemorating her. Given her complicated legacy, it may be a while until she gets one. But for around $9 a pound, you can buy coffee roasted exactly to the Iron Lady’s specifications at 49 Levinsky Street in Tel Aviv, and attempt to drink the potent (and somewhat burnt) brew at your own kitchen counter. “People come especially to buy Golda coffee,” notes Rafaelli. “Clients from [her neighborhood] who used to buy it there, and people who heard about it and come especially to buy it.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook