Biologists Threw a Fluorescent Frog Rave in the Amazon, for Science

Turns out many of the frogs glow, maybe to communicate.

The Amazon rainforest is full of color—and not just the enveloping green of palms, shrubs, and vines. From scarlet macaws to yellow eyelash vipers to pink river dolphins to countless flowers, it’s bursting with other hues, too. And that vibrancy somehow seems to continue after the sun goes down, if you have the right eyes to see it.

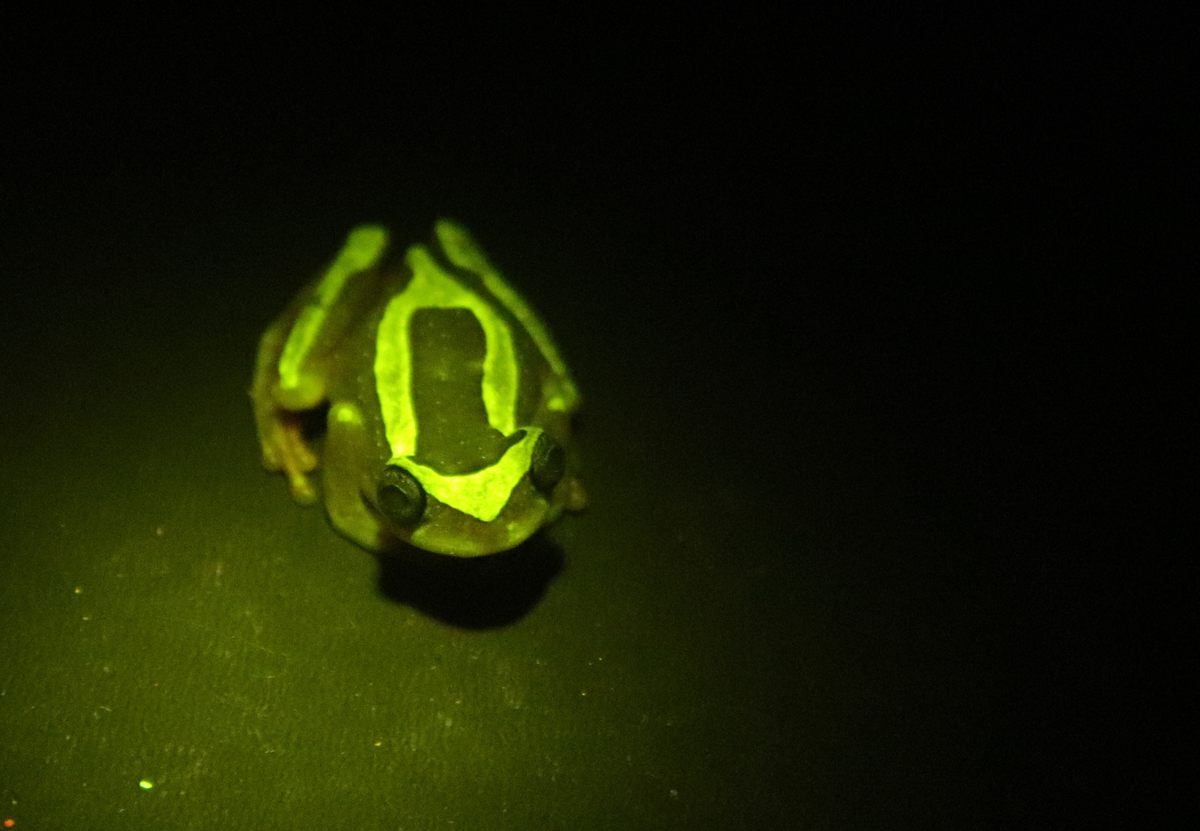

During the dwindling hours of daylight, according to a new study, certain frogs may actually glow to communicate. These frogs don’t shine on their own like bioluminescent fireflies, but they biofluoresce. This means that they absorb light at one wavelength, or color, and shoot it back out at a longer wavelength. Against a dark backdrop, this gives them a dim glow. Using a colorful array of lights—from violet to cyan to green—researchers from Florida, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia tested what wavelengths made frogs stand out. They found that more frogs give off such evening light displays than previously thought. The paper, released as a preprint at bioRxiv.org, has more than tripled the number of frog species tested for biofluorescence, adding 151 species of frogs and toads in total.

Each day, the team discovered more species that biofluoresce, says lead author Courtney Whitcher, a doctoral candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at Florida State University in Tallahassee. “We’re living in a glowing fluorescent world that’s just waiting to be discovered.” Every single species they studied showed some level of fluorescence.

The closest we humans get to this glowing, psychedelic world is when we step under a black light. Our teeth and fingernails, as well as many bodily fluids, absorb ultraviolet light and reemit it at a different wavelength, causing them to shine brightly. Just because parts of us can fluoresce doesn’t mean they’re doing so for any particular purpose. The same is true for many other fluorescing elements in the natural world, from glowing fur to feathers, says visual ecologist Michael Bok at Lund University in Sweden, who was not involved in the study. “There’s a lot of meaningless fluorescence in the world,” he says. But that doesn’t appear to be the case for these rainforest frogs.. Their skin absorbs ambient blue light and bounces it back as an eerie green glow—which their eyes are sensitive enough to pick up.

“Courtney’s extraordinary fieldwork allows us to demonstrate that amphibians’ sensory world is quite different—they have capabilities that we humans can only dream of,” says coauthor Santiago Ron, a biologist from Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

Like humans, frogs have rods and cones in their eyes. Rods help us see dim light, and cones help us see bright light and colors. Unlike humans and all other terrestrial vertebrates, amphibians have two types of rods, which let them discriminate between colors in near-dark conditions. Some rods are attuned to blue light—which dominates the evening—and even more are sensitive to green light, which allows them to sense even subtle glowing green. So it stands to reason that, if many of these frogs can see green glows that other creatures can’t, then maybe they’re making green glows as a way to signal one another, or at least declare their presence to each other.

Biofluorescence in frogs is a relatively new discovery. The phenomenon was first spotted in the polka-dot tree frog of South America in 2017, and by complete accident. Researcher Julián Faivovich and his colleagues at the Natural Sciences Museum in Buenos Aires, Argentina, shined a UV light on a frog to look at some tissue samples and were shocked to see its whole body fluorescing. Before this new study, some 42 frog species had been tested for fluorescence, with about half exhibiting it. But those studies only used one or two different light sources (often ultraviolet and violet), says Whitcher. The new study enlisted five wavelength ranges that more accurately represent the light available at twilight. With this novel approach, they were able to identify fluorescence in many new species, and six previously dismissed as non-glowing.

Whitcher and the South American research team spent 10 weeks, from March to May 2022, sampling 528 individual frogs across Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil. Their evenings involved scouring trees, leaves, and pools for subjects. The frogs they caught were then whisked to a local research station for long nights of rave lights. Until the wee hours of the morning, researchers donned filtered goggles—to help block out added light sources and better see fluorescent markings—and peered at frogs under a series of fancy flashlights, using filtered cameras and wavelength-reading instruments to record their findings.

“They were long days,” says Whitcher, “but they were a lot of fun and full of discovery as well.”

Every one of the 151 species they found showed some level of fluorescence—from glowing back markings to belly splotches to entire faces and limbs. Some barely glowed, while others reemitted almost all the light they absorbed. They found that frog skin absorbs the bountiful blue of dusk and sends it back out to match the sensitivity of those green-sensitive rods in their eyes. It’s a vision double-whammy. And it takes place in a way that matches frogs’ activity and ecology, and the physiology of their eyes. Researchers can’t hop to any definitive conclusions, but this suggests that fluorescence may allow frogs to communicate with each other, says Whitcher. While frogs are very vocal communicators, this may serve as a secondary means of being in touch, she adds.

Amartya Tashi Mitra, a doctoral student who studies lenses and eye development in insects at the University of Cincinnati, says that the evidence is convincing. “It also seems that the species that they found to fluoresce seem to be things like tree frogs with really big eyes,” he says. “It’s quite likely that those species are using their vision to perform complex tasks like signaling. They didn’t find this kind of fluorescence in aquatic species, which have much smaller eyes and live in murky waters, so it does seem that this is something that evolved by a sensory drive to serve a very specific purpose.”

And because they tested a range of wavelengths, there were other intriguing observations. They saw that some frog skin also fluoresces orange, sometimes in addition to or instead of green. But frog eyes aren’t well adapted to seeing this wavelength. This fluorescence, they propose, could be for a different target audience, such as predators. The orange could suggest they’re poisonous, or help camouflage them in the leaves around them, which biofluoresce red due to their chlorophyll, says Whitcher.

Bok says he is generally skeptical about the role fluorescence actively plays in animals’ lives, but that this research stands out. “This paper is an example of actually trying to examine these fluorescent patterns in the context of natural light and the observer’s visual system, which is the correct starting point,” he says. “They’re coming at it from the right angle. I’d be very happy and excited if there was a case where it’s actually being used. That’d be a neat thing to discover.

“There is a chance that these frogs are actually using fluorescent signals in a narrow window at twilight when the natural light conditions are very specific, but we still need to see evidence, not just that their eyes can detect the fluorescence, but also that the animals care, and alter their behavior based on the fluorescent cues,” he adds.

Whitcher is continuing to look into that. In the study, she noticed that most strongly fluorescing body parts were often the undersides and throat, which are used in communication and can be especially important for attracting mates. Now, she’s testing what difference fluorescence makes in the mates that females choose. We’ll see who gets glowing reviews.

There is so much left to learn about the secret lives of frogs, Whitcher says. “There’s over 7,000 frog species known currently, so we still know just a minuscule amount of what this fluorescent pattern looks like across all of the frog species that are known,” she says.

To help, Whitcher has enlisted the public. In July 2020 she launched Finding Fluorescence, a citizen science project where people can take black lights into their own backyards and record which organisms biofluoresce. So far there have been 36 observations uploaded, with almost every one completely new to science. “Not only is it a fun activity to take a blacklight out into your backyard and get to look at cool glowing things, but that can legitimately help scientists make new discoveries,” says Whitcher. “We’re living in this glowing world that anyone has the ability to discover.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook