The Biology Teacher Resurrecting Germany’s 500-Year-Old Mite Cheese

At this charming farm, quirk meets quark to make a unique cheese.

In the mostly rural Burgenlandkreis county, just southwest of Leipzig in Germany, a tradition of making cheese using millions of live mites dates back at least 500 years. Today, there is only one commercial maker of Milbenkäse left: Würchwitzer Milbenkäse Manufaktur, a two-man operation founded in 2006 by Helmut Pöschel, a retired biology teacher, and Christian Schmelzer, a theologian.

“After the Wall came down, there were only a small number of people left producing mite cheese. Helmut then kept it going from his mom and grandma, and tried to make it a bit more popular,” Schmelzer says, “but it was also a bit [of] a joke, like ‘Look what we are eating, such strange things.’”

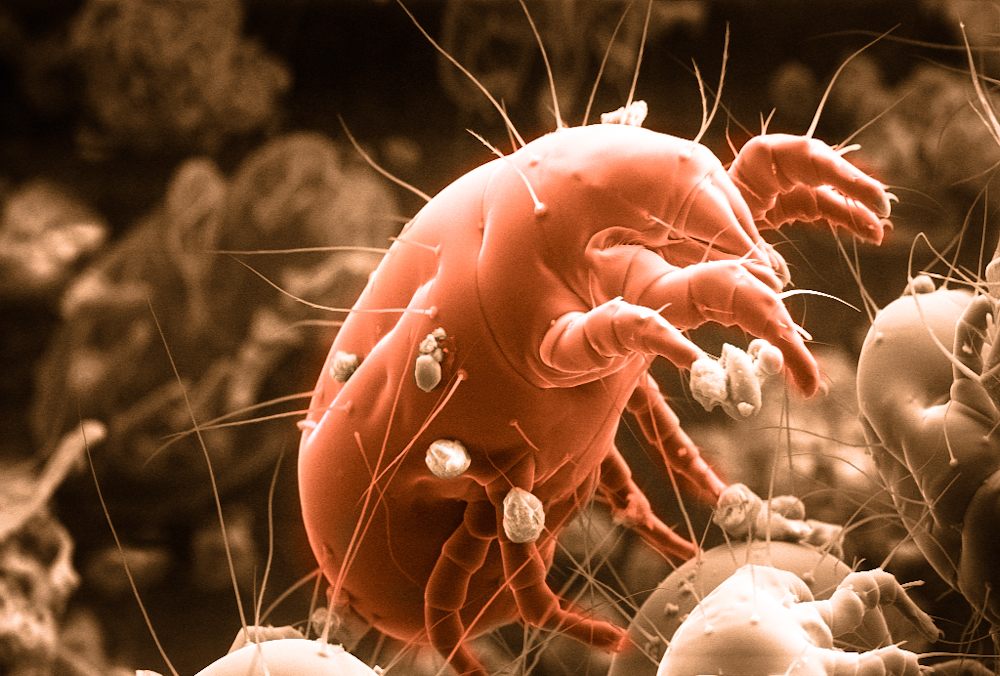

For those unfamiliar with Milbenkäse, the “strange” aspect is the rind, which isn’t a rind at all, but 50,000 or so live mites who were instrumental in transforming a log of quark or curd into this unusual specialty. Given both its limited availability and the fact that it’s coated in tiny arachnids, the cheese isn’t widely consumed, but among chefs and laypeople who know it and love it, Milbenkäse is typically eaten cut into thin rounds and spread on top of buttered rye bread, and pairs well with wine, beer, or cocoa.

If mite-coated dairy isn’t to your taste, you share an aversion with the leadership of the former German Democratic Republic. After surviving World War II, this regional specialty nearly disappeared under the GDR, which banned the production and distribution of live-mite food products. What survived was a dwindling pool of farmers and grandmothers making the cheese in wooden boxes at home for private consumption, “producing it like you’re doing your own sourdough,” Schmelzer explains. In the village of Würchwitz, Pöschel’s mother had kept her strain of mites going. Pöschel brought them to his biology classroom, for his students to observe through a microscope (at .5 millimeter, Tyrophagus casei L. is visible with light magnification), while also making cheese “in the private sphere, with the old women of my village,” he says.* He made the leap into commercial production after a chance meeting 20 years ago with Schmelzer, a teenager who was curious about Milbenkäse, and whose grandfather taught at the same school as Pöschel.

At Pöschel’s farm, hundreds of millions of mites reside in untreated wooden ammunition boxes, where they’re kept in their preferred living conditions: dark, cool, and humid. Pöschel and Schmelzer place rolls of dried quark and curd in the boxes, which the mites begin to eat. In the course of feasting, they secrete digestive enzymes that ripen the dairy into cheese.

Today, Pöschel is 79, retired from teaching (a contemporary Renaissance man, he still tends to one of his other métiers, a film studio making short comedic films), and spends around five hours a day feeding the mites, tending to their temperature and humidity levels, and fielding guests at the one-room Milbenkäse Museum, where he receives by-appointment-only visitors almost daily. Schmelzer, age 38, commutes between Würchwitz and Berlin, where he has a communications firm that works with the city’s churches and Protestant schools.

Schmelzer calls mite cheese–making a hobby, albeit one that’s demanding enough, as the only business around, that he sometimes enlists his parents and his husband to help with the 1,000 or so annual orders. Business could be even more brisk, but they aren’t permitted to ship anywhere except the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland. Under E.U. regulations, the sale of food products that contain live animals like mites is permitted, but not all countries are as open-minded.

Schmelzer’s mother also harvests the elderflower that comprises part of the classic Milbenkäse-Roll. The modestly pungent hard cheese is made with skimmed quark rolled with caraway seeds, the same way it was prepared during Martin Luther’s time (the original Protestant’s hometown of Eisleben is about 25 miles from Burgenlandkreis). A faint lemon aroma doesn’t come from the dairy but the mites, who emit a defensive secretion containing neral, which is also an essential component of lemon oil.

There’s a waggish spirit to the cheesemakers’ enterprise. Pöschel explains that he got his nickname, Humus, from his own biology teacher, because “when we went on nature excursions, I was always digging in the dirt,” looking for bugs in the humus layer of topsoil. He and Schmelzer discuss their mites as if they were beloved, if persnickety, colleagues. “We have the most employees in all of Germany,” Schmelzer says, and those employees will eat only organic dairy. When their tiny colleagues suddenly refuse to eat a batch of quark, the cheesemakers have to find a new supplier. “It’s really a bit of a game to keep the mites happy,” says Schmelzer.

Off-duty, the mites’ wooden boxes are filled with nutritious rye flour to tide them over before their next quark-feeding session. If they’re too hungry when a log of dried quark or disc of curd is placed in their box, “they will eat the whole cheese,” Schmelzer says. “And you don’t want that. They can eat fifty percent, but not the whole thing.” He and Pöschel also have to carefully dry the quark before rolling it into little logs. “When it’s too dry, the mites don’t want to eat it. When it’s too wet, they will stick, and then you have to scrape them off,” he explains. And woe betide anyone who handles the mites and fails to thoroughly clean their fingernails afterward—the trapped critters will eat those, too.

The dairy’s Milbenkäse-Rolle is the most traditional form of mite cheese, but Schmelzer and Pöschel also make two variations. Himmelsscheibe, their mildest offering, is named after a Bronze Age plate discovered in the town of Nebra, about 44 miles (70 kilometers) away. Dotted throughout with caraway seeds, and formed into large, flat discs, the cheese resembles the astronomical phenomena depicted on the bronze antiquity. The name Himmelsscheibe also translates to “slice of heaven,” and apparently the mites agree: Made from a mix of cow and goat curd from a nearby dairy, the cheese was originally just mite-breeding material, because they reproduce where they eat. “I would say they breed on anything, but they breed better on this because they love to eat it,” Schmelzer says. “They never say no to it. And then we said, ‘Oh that also tastes really nice, so let’s sell it.’”

Lastly, made from sour-milk quark and caraway seeds, with a stronger, more bitter flavor than dairy’s other two cheeses, the hockey puck–shaped Himmelskomet was also named as a celestial tribute, to the smaller, comet-like star depicted on the Himmelsscheibe itself.

Schmelzer and Pöschel may be keenly aware of their mites’ needs and preferences, but until the 1800s, people didn’t know the mites existed at all. “During the Medieval Ages, they understood, When I put quark into a box with bread flour and leave it there for two or three months, this little cheese I made out of curd stays fresh. What they didn’t understand was that there were mites living there in the flour,” says Schmelzer. The earliest known written reference to mite cheese dates back to an early 16th-century inheritance agreement, which made a particular stipulation for the deceased’s widow, allotting her 12 pieces of so-called bread-flour cheese every two weeks.

Having rescued this tradition from near-oblivion, today the cheesemakers know more about Milbenkäse than anyone. But they frequently share that knowledge, and their mites, with researchers from universities and pharmaceutical companies around the world (one area of study is examining whether eating cheese mites may alleviate allergies to their relative, the dust mite). Pöschel has played host to a slew of international visitors over the years, as mite researchers often obtain their specimens like anybody else: by going to see him on his farm, having a beer or a glass of wine, and buying some cheese. As a result of this exchange of knowledge (and specimens), the mites now have an entire book devoted to them, by Satoshi Shimano, a Japanese professor and researcher.

At home in Würchwitz, Pöschel erected a mite cheese monument on a village green, with a special hole where he can insert a lump of the cheese, which he mostly does when he has visitors, in order to impart its fragrance. He says that the region is “very proud” of the cheese’s comeback, and now hosts an annual mite cheese festival in June, which typically attracts around 1,000 visitors. Pöschel says he’s having fun doing his part to save an old tradition, joking that he’s “infected” many of his neighbors to keep Milbenkäse going in the surrounding villages.

“It makes me proud, knowing the tradition will outlive me.”

* Pöschel’s responses have been translated from German.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook