A Guide to the World’s Most Comforting Foods of Grief

In an age of distance, we can still connect in the kitchen to mourn, memorialize, and heal.

According to the latest figures from Johns Hopkins University, more than 170,000 people have died from COVID-19 worldwide. The world is mourning a massive loss of life while also grieving the smaller, yet still significant, loss of our old ways of living. Along with our daily routines, social-distancing restrictions have impacted the ways we mourn. Communities can no longer gather in large groups to support the bereaved at traditional wakes, funerals, or shivas.

While we can’t congregate, we can still cook. Around the world, mourners express empathy and self-care through food. From “feeding” the dead with fried dough in Kyrgyzstan to the sweet solace of Amish funeral pie, we use food to process our own grief and to acknowledge the grief of others. Many of these traditions involve the community stepping in to feed those in mourning. Depending on your local laws, you might still be able to provide this consolation: In the United States, the CDC says there is currently no evidence to suggest that COVID-19 can be transmitted through food. So, provided you follow safety precautions for preparation and drop-off, you can leave your friends that casserole.

Even if we’re just cooking for ourselves, food can help us heal during difficult times. In a recent article about pandemic-related grief in The Atlantic, John Dickerson wrote, “Many of us are distracted, enraged, scared, or just doing what we can to manage a full plate of immediate worries. But in this period, we should spare a moment for sorrow and grief.” Here are eight foods that help mourners around the world to heal, reflect, and memorialize in such moments. They hail from kitchens spanning from Jamaica to Iran, from religions ranging from Orthodox Christianity to Judaism. But what they have in common is a comfort provided by ritual and nourishment, by memories and connection. Whatever food provides you comfort in times of grief, spare a moment for a meal.

Funeral Potatoes

While the origins of Utah’s classic casserole are murky, most sources credit its rise in popularity to a women’s organization within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Known as the Relief Society, one of the group’s chief responsibilities was attending to the needs of the bereaved. This, of course, included their meals.

Mourners found themselves comforted by a corn flake–topped combination of shredded or cubed potatoes, cream of chicken (or mushroom) soup, sour cream, butter, and grated cheddar cheese. It’s still served at post-memorial gatherings and church potlucks today. In her 2012 memoir, The Book of Mormon Girl, Joanna Brooks describes the meal as “heart-stopping, lipid-soaked church-dinner comfort food.” But the ingredients weren’t selected simply because they were hearty and delicious; they were pantry staples. In fact, they’re almost always inside an LDS community-member’s pantry, a holdover from the Church’s post-Depression push for maintaining a three-month food supply at all times. As such, funeral potatoes can be prepared at a moment’s notice when someone passes away.

While the dish may have been created for times of sorrow, it’s become a point of pride for Utahns. When Salt Lake City hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics, they developed an official commemorative Olympic pin that featured funeral potatoes.

Those looking to wrap themselves in the warm, crispy, cheesy embrace of funeral potatoes can try this recipe from MormonChurch.com.

Halva

Recipes and spellings for halva vary across the Middle East, Central Asia, and India. Most versions appear in the form of a sweet, dense confection that’s enjoyed year-round. But in Iran, Turkey, and Armenia, halva is also strongly associated with times of mourning. In a Food52 article, journalist Liana Aghajanian recalls, “At the funerals I attended growing up in Iran, wading through a sea of black outfits with the distinct smell of frankincense in my nose, I’d search through the crowd for my aunts and the glistening, aluminum foil–wrapped treasure they carried on a tray.” Aghajanian, whose family is Armenian, consumed halva as part of a memorial lunch known as hokeh-jash, which translates to “soul-meal.”

On her blog Turmeric and Saffron, Persian chef Azita Mehran describes the process of making and sharing funeral halva as “both therapeutic and somewhat healing.” Mehran’s version includes rose water, itself a venerated funeral food that is sprinkled over graves.

If you have rose water, try Mehran’s recipe. If you don’t, Aghajanian’s recipe for halva requires just sugar, water, flour, and butter. Sometimes the sweetest solace comes in the simplest forms.

Koliva

Wheat is a longstanding symbol of both death and everlasting life. In many cultures, the personification of Death holds a scythe for “reaping” souls like wheat at the harvest. But as the fallen grain of a dead plant can generate future crops, Christians believe wheat also represents eternal life. For Orthodox Christians in the Balkans, these dual meanings mingle in a sweet, subtly nutty dish that honors the dead.

When the bereaved arrive at an Orthodox Christian funeral, they come bearing koliva. Particularly prevalent in Greece, the dish is built around unprocessed kernels of wheat, otherwise known as wheat berries. Just preparing the berries makes for a time-consuming tribute, taking two days to soak, cook, drain, and dry the kernels. During this time, relatives are supposed to pray and think of the deceased. To that base, one adds a medley of flavorings that represent the sweetness and abundance of life, including raisins, cinnamon, anise, sesame seeds, pomegranate seeds, ground nuts, and honey. Cooks often add a generous dusting of confectioners’ sugar, then use nuts, Jordan almonds, or dried fruit to form a cross and the initials of the deceased. With a few sprigs of parsley serving as “grass” beneath the cross, the mound evokes the burial site itself.

Despite its sweetness, koliva is a sacred food that’s meant to be eaten solemnly and not for pleasure. In fact, The Washington Post’s recipe notes that its yield of 40 servings is so high because each serving is a mere spoonful that a funeral attendee deposits into a paper bag to respectfully consume after the service. In addition to the funeral, koliva is also prepared for memorials at various intervals after a death, typically after 40 days, six months, and one year.

Mannish Water

Not all mourning rituals are explicitly solemn affairs. In Jamaica, family and friends gather for a Caribbean wake known as the Nine Nights, during which they share stories, dance, play games, and eat. The goal is to encourage the deceased’s spirit, known as a “duppy,” to depart. If the duppy doesn’t leave, it will stay in limbo and become an angry spirit that haunts the living.

The Nine Nights are punctuated by drumming and dancing that offer an energetic contrast to death. This vitality is also conveyed via mannish water, a goat soup with alleged aphrodisiac properties. Recipes vary but generally use a base of a male goat’s head, entrails, and testicles that mingle in a broth of carrots, potatoes, and green bananas. Most cooks add a kick with white rum and some heat courtesy of Scotch bonnet or habanero peppers. At once gamey, savory, and spicy, the soup often gets paired with bammy (a small, cassava-based cake), white “hard-dough” bread, and white rum.

Because of its connection to reproduction and new life, mannish water also appears at celebratory occasions like weddings. If you can track down its ingredients, try this recipe from Jamaican chef Sian Rose. If you can’t get your hands on specific goat parts, Rose says just goat meat will do.

Amish Funeral Pie

While travel restrictions have limited our ability to attend funerals both near and far, journeying great distances to pay respects once dictated the types of food attendees would bring. In the Amish and old-order Mennonite communities of 18th-century Pennsylvania, that meant the spoil-proof sweetness of raisin pie.

The bereaved would be responsible for providing their guests’ meal (which led to the rise of culinary opportunists known as “funeral runners,” who attended services just for a free dinner), but the visitors brought dessert. Raisin pie became a favorite choice, as it traveled well, offered sweet comfort, and used non-seasonal staples. Like funeral potatoes, the pie’s filling relied on common pantry items—raisins, sugar, eggs, flour, salt, and lemon—that could be transformed into a treat at a moment’s notice. Also like its Utahn counterpart, the dessert was such a common sight at post-memorial meals that it earned a new moniker: “funeral pie.”

Although it’s easier to make or purchase fresh-fruit pies today, Pennsylvania-based Amish communities still bake their beloved funeral pie. Its ingredients are likely lurking in your cupboard. Try this modern take from Pennsylvania’s York Dispatch.

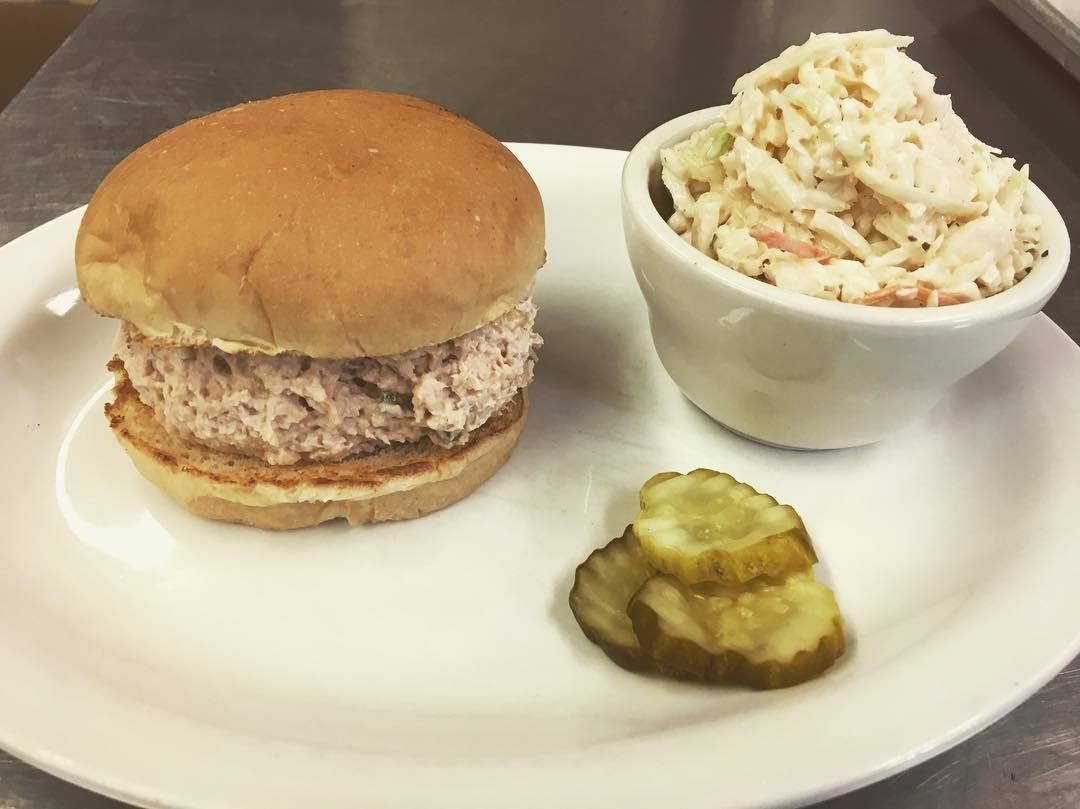

Ham Salad

Some funeral traditions offer solemn, moving moments of connection. Others can lean more toward frivolous status symbols. In late 19th-century England, ham was one such status symbol. Receiving a stylish service came to be known as being “buried with ham,” as not just anyone could afford such meaty extravagance at their funeral tea.

While ham isn’t quite the display of opulence it once was, it’s still prevalent at British and American funerals in baked and cold-cut forms. In the United States’ Upper Midwest, Mid-Atlantic, and Southeast regions, this culinary tradition evolved into the mayo-based delight known as the ham salad. Though some cooks added in the likes of hard-boiled eggs, celery, or onions, the basic recipe for the “salad” used ground ham, mayonnaise, and pickle relish. Slathered between slices of white bread or atop crackers, the cheap, filling spread rose in prominence at post-Depression American funeral luncheons.

Like funeral potatoes, the ham-salad sandwich was a favorite among church-based aid societies who brought it to year-round potlucks and post-memorial gatherings. Try this recipe from the cookbook for The Ladies’ Aid Society of the Evangelical Church of Our Redeemer, based in St. Louis, Missouri.

Lentils, Bread, and Eggs

After returning home from the burial service, Jewish mourners tuck into the seudat havra’ah. According to the Talmud, this “meal of consolation” must be provided for the deceased’s family by friends and neighbors, as the bereaved will be too distracted by their grief to care for themselves. While spreads can vary, several symbolic foods are common. Circular foods—namely, lentils, bagels, and round rolls—represent the cycle of life, which involves not only birth and death, but joy and sadness. Lentils also harken back to the stew Jacob is said to have prepared for his father, Isaac, after the death of his grandfather, Abraham. Eggs, a symbol of new life, typically appear in hard-boiled form, a preparation that doubles as a metaphor for resiliency in the face of tragedy. Both lentils and eggs are also smooth without openings or “mouths,” meant to symbolize the mourners’ sorrow rendering them unable to speak.

Anyone wanting a greater challenge than hard-boiling an egg can try food-history blogger Tori Avey’s recipe that attempts to re-create Jacob’s lentil stew.

Borsok

In the Central Asian country of Kyrgyzstan, honoring the dead involves frying balls of dough into puffy nuggets known as borsok (also spelled boorsok or borsook). The bread is a simple mixture of flour, water, salt, sugar, butter, and yeast that sizzles in oil. But the ritual surrounding its preparation is far more important than flavor or flair.

While some foods on this list are meant to nourish the living, the ritual of preparing and eating borsok is meant to honor and “feed” the deceased. Some believe that as women fry the dough in a kazan (a wok-like frying pan), the resulting smoke carries the cooks’ prayers to heaven and appeases the spirits of the dead. According to the BBC, the name for the ritual of cooking and consuming borsok, jyt chygaruu, even means “releasing the smell.”

When the borsok is ready, it’s scattered in puffy piles across a table. After someone recites verses from the Koran, the family prays for the deceased’s well-being in the afterlife. Then, they eat.

You can try to make borsok at home by following this recipe and photo series from a Peace Corps volunteer who recorded her experience making it with her host family in Kyrgyzstan.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook