From Shark Tanks to the Deep Sea: A Day in the Life of a Monterey Bay Aquarist

What it’s like to care for fascinating animals at an aquarium on the edge of the Pacific.

What do you want to be when you grow up? When you’re little, your answers to this question may have skewed toward the fantastic: queen, dinosaur, marine biologist. But Briana Fodor is living the dream; she actually grew up and became a marine biologist, working as Senior Aquarist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California.

“An aquarist is someone who is responsible for taking care of the fish and invertebrates at the aquarium,” Fodor explains – it’s another word for an aquarium keeper. In her job, she monitors animals’ health, cleans their exhibits, and feeds them, which can include diving into their tanks. Which would mean one thing if she would be diving into a tank of octopuses or cute little clownfish. But the afternoon I spoke to her, Fodor would be helping with the aquarium’s hammerhead sharks.

Scalloped hammerhead sharks have a head that looks like, well, a hammer, with one eye located on each end. Because of their heads’ broad shape, hammerhead sharks are more easily able to sense prey like stingrays that are buried in the sand. (They also eat squid, crustaceans, and fish.) You might think Fodor would dread working with sharks, but actually, she says, “they usually are the more skittish of the animals at the aquarium.” If you’re planning to swim off the coast of California, maybe even in one of the coastal lagoons where hammerhead sharks are pupped, fear not: scalloped hammerheads are not generally aggressive towards humans. Their mouths are so small, how would a person even fit?

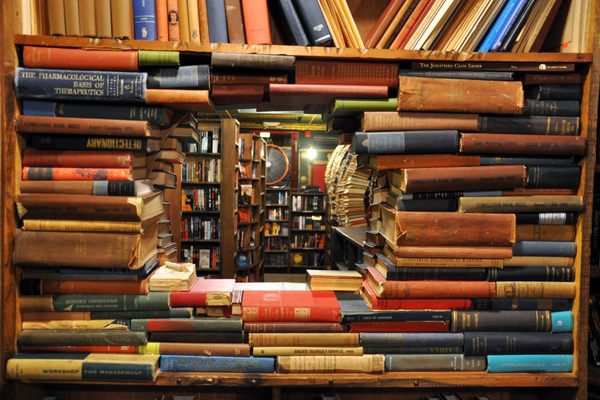

Fodor’s days as an aquarist generally start the same way. She takes care of the exhibits she’s responsible for, feeding the animals and cleaning their tanks. “We even vacuum the gravel to help clean,” she says. There are a lot of exhibits to take care of at Monterey Bay: the aquarium has over 200 exhibits, with 75,000 different animals from 801 distinct species. It has African penguins, which live along the coast of South Africa and so are used to central California-style weather. It has giant green anemones, which are a color of neon green most often seen on Nickelodeon slime, a color that comes from the anemone’s symbiotic relationship with microalgae. The aquarium has sea otters, sea urchins, and sea turtles; stingrays and bat rays; and so, so, so many kinds of jellyfish.

After her morning caring for her assigned tanks, Fodor rotates through teams of aquarists helping out on larger exhibits. On the day we spoke, she was working in the Monterey Bay Habitats tank, a 90-foot-long tank with walls 3-4 inches thick, holding 350,000 gallons of water. The hourglass-shaped tank was designed to give sharks room to glide and turn, and the sharks represented range from the broadnose sevengill shark (up to 10 feet long, eats other sharks) to the Pacific angel shark (spends its days buried in the sand). That morning, though, Fodor was working with a different massive fish.

“I was diving with our giant sea bass this morning,” she says, “getting completely ignored by them.” Giant sea bass are massive, growing up to 7.5 feet long and weighing as much as 557 pounds, making them the largest nearshore bony fish found in California’s coastal waters. But giant sea bass are also gentle and even like to have their chins scratched during feedings. They look lumpy and endearing, like if a rock became sentient and also, somehow, adorable.

The aquarists “target-train” the giant sea bass to make them more comfortable with people in the water, which is helpful whenever they need a procedure. Each of the three giant sea bass in the aquarium has its own assigned target, held by an aquarist who dives into the tank. “We’ll reward [the giant sea bass] if they do what we’re asking, which is usually just to come to the target.” Often they’ll do this near a stretcher made of blue tarp and white poles, to habituate the giant sea bass to the device, which is used to remove them from the water when needed, such as a recent operation to see how much the sea bass weighed.

“Today I had one of our sea bass who has a gray triangle that he comes to. I totally got snubbed today,” Fodor says. Her assigned sea bass just swam by and looked at her. “He knows I have the food. He was just like –” here Fodor mimes the fish’s skeptical glance. “‘Okay.’ Kept going, and that was the end of the session.”

Why did the sea bass ignore her? Part of it has to do with the fact that the Monterey Bay Aquarium is uniquely situated on the edge of the Pacific Ocean, with an outdoor tidepool exhibit, and viewing decks where you can watch animals out on the open water. The aquarium has open-system tanks that pull nearly one billion gallons of seawater per year into its tanks. This means that whatever the temperature is in Monterey Bay, the tanks in the aquarium will be affected. “The Bay’s been a little colder,” Fodor says, “so that water’s coming in, so that means our exhibits are a little colder, too.” And when the water is colder, the animals don’t eat as much. “So today, [the giant sea bass] were not feeling it.”

Fodor’s work isn’t limited to the tanks inside the aquarium; its location on the Pacific means she’s also on the field diving team that works in the ocean. There, the team does surveys, helps with restoration work, and collects specimens for the aquarium. “Local species,” she explains, “just so we are able to show all of our guests all the really cool animals that are just off our back deck of the aquarium.” Most often, they collect marine invertebrates like sponges, barnacles, and mussels. (The orange puffball sponge, for example, looks like a Nerf ball that was left out in the rain too long.) Occasionally the diving team collects fish as well, but Fodor says the fish thrive at the aquarium, meaning they do not often need to be replenished. “And we have some people on-site who are doing really cool work with aquaculturing fish.” In layman’s terms, this means the aquarium raises its own fish.

All of the diving she does is part of what inspired Fodor to become an aquarist in the first place. “I started doing a lot of field work in college as a dive assistant,” she says. She considered going to grad school, but quickly learned she hated how much of the time she was stuck at a computer, analyzing data. “So I was able to intern after college at an aquarium, and I realized I could combine – and get paid for – diving, but also then be able to use a lot of the hands-on skills and just the knowledge I’ve gained over the years from marine biology.”

And for that interest in marine biology, she has the Monterey Bay Aquarium to thank. She’s from the Los Angeles area, and grew up coming to the aquarium as a kid. Her family would come up the coast, tide pooling a couple hours south of Monterey in Pismo Beach, “and I would always beg [my parents], ‘Can we go up to the aquarium just for the day?’ And so I vividly remember coming here as a little kid.’” Fodor worked at a different aquarium for years, but in a full circle moment was hired by the Monterey Bay Aquarium a couple years ago

With all of her knowledge and years of experience, does she have a favorite animal to work with? No, she says. “I always tell people my favorite animal can change daily.” For today, at least, it’s a fish that had been growing in one of the behind-the-scenes tanks, a cabezon. (Meaning “large head” in Spanish, a cabezon is a blotchy, 3-foot-long fish found on the rocky shore of the Pacific all the way from Baja California to Southeast Alaska. A cabezon will eat, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium website, “whatever fits in its mouth.”) Speaking about her favorite fish, Fodor says, “He’s just super cute and personable, and we just moved him in to one of the exhibits.” So it’s not even a favorite species, it’s a favorite individual fish? “Oh yeah,” Fodor laughs. “That’s usually what it turns into now. It’s like, OK, this guy. He just has that personality.”

This post was sponsored by Visit California. Learn More.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook