The Giant Frog Farms of the 1930s Were a Giant Failure

The get-rich-quick scheme couldn’t fill the world’s appetite for frogs’ legs.

The American Frog Canning Company had a pitch for people struggling to make a living in the 1930s, when jobs were scarce and money tight. The company promised a good market and a steady source of income. It was simple enough, the company promised. All you need is a small pond and a few pairs of “breeders” in order to …

Frog farming was “perhaps America’s most needed, yet least developed industry,” wrote Albert Broel, founder of the American Frog Canning Company and author of Frog Raising for Pleasure and Profit. With wild populations dwindling, the demand for frog meat was greater than its supply. The market for it had the potential to grow as exponentially as a new stock of frogs could.

Those few pairs of breeders, Broel explained, would produce tens of thousands of tadpoles, and it would take just this one generation to provide a frog farmer with a ready crop. At $5 a dozen (about $100 in today’s dollars), frogs could turn into a fortune. And people leapt at the opportunity. They wrote to Broel for copies of his frog-raising handbook, paid for a full course of frog-based learning, and ordered their breeders to start their own farms.

From his base outside of New Orleans, Broel became America’s leading frog canner and promoter of frog culture. In one family portrait, he stands, stout and round-headed, on his cannery’s steps, in a well-tailored white suit. On the step below is his notably taller wife, and the couple is proudly flanked by two white statues of giant frogs, which reportedly had light-up eyes that blinked red in the night.

“I think his story is absolutely amazing,” says his daughter, Bonnie Broel, who keeps a collection of frog memorabilia in her Victorian mansion in New Orleans. “He came to this country and started a brand new business that no one had ever heard of, with nothing.”

Broel was a canny survivor, a descendant of Eastern European nobility, a practitioner of holistic medicine, a real-estate investor, and one of the few people who ever managed to make money from frogs. Because, while starting a frog farm was easy enough, raising frogs to market means fighting nature—and losing.

According to the story he told, Albert Broel started his frog business because of his mother. In one version, she had stomach trouble as a young woman. In another she stopped eating meat at 80, doctor’s orders. “As far back as I can remember, my mother used to say: —‘Son, if you want to make a success in life—Raise Frogs,” Broel wrote.

It wasn’t his first choice of profession. After settling in Detroit with a degree in naprapathy, a holistic wellness field focused on connective tissues, Broel opened a medical practice, married, and bought an apartment building. After being chased out of the medical profession for operating without a proper license, he followed his mother’s apocryphal advice. He started growing frogs at a large scale, on a 100-acre farm in Ohio, and experimenting with canning frog meat. With the money he made, in 1933 he moved his family to Louisiana, in search of a better climate for frog farming.

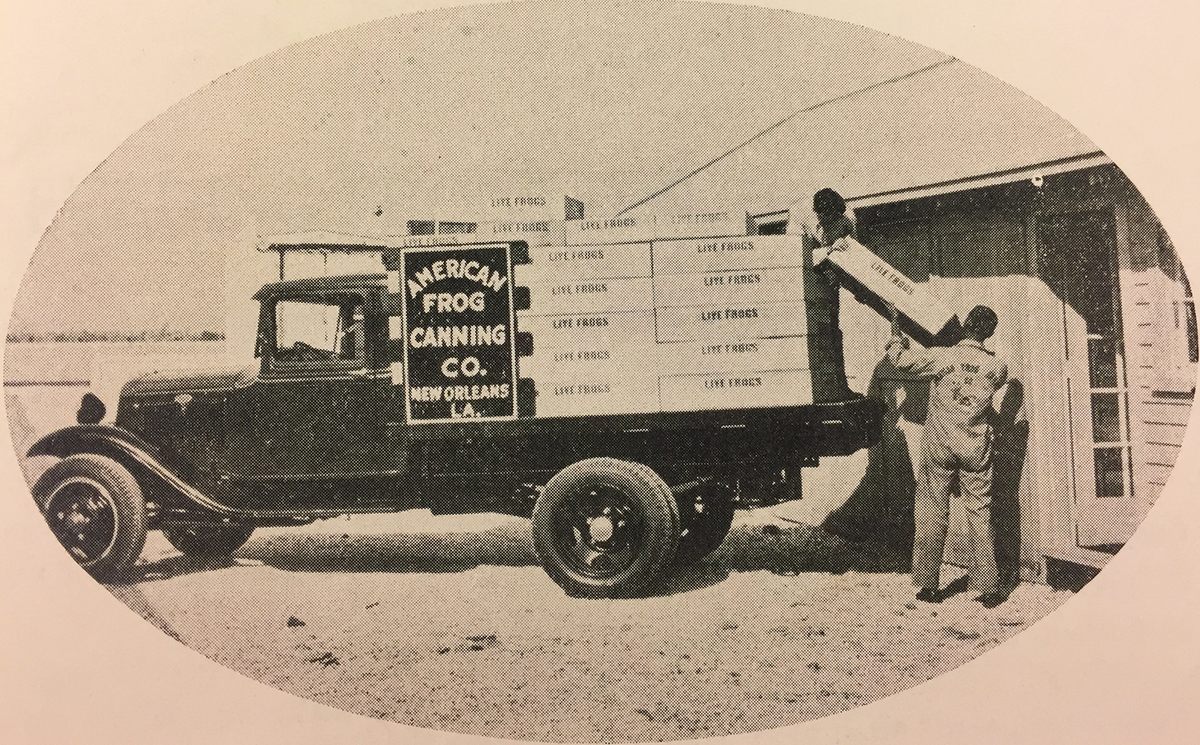

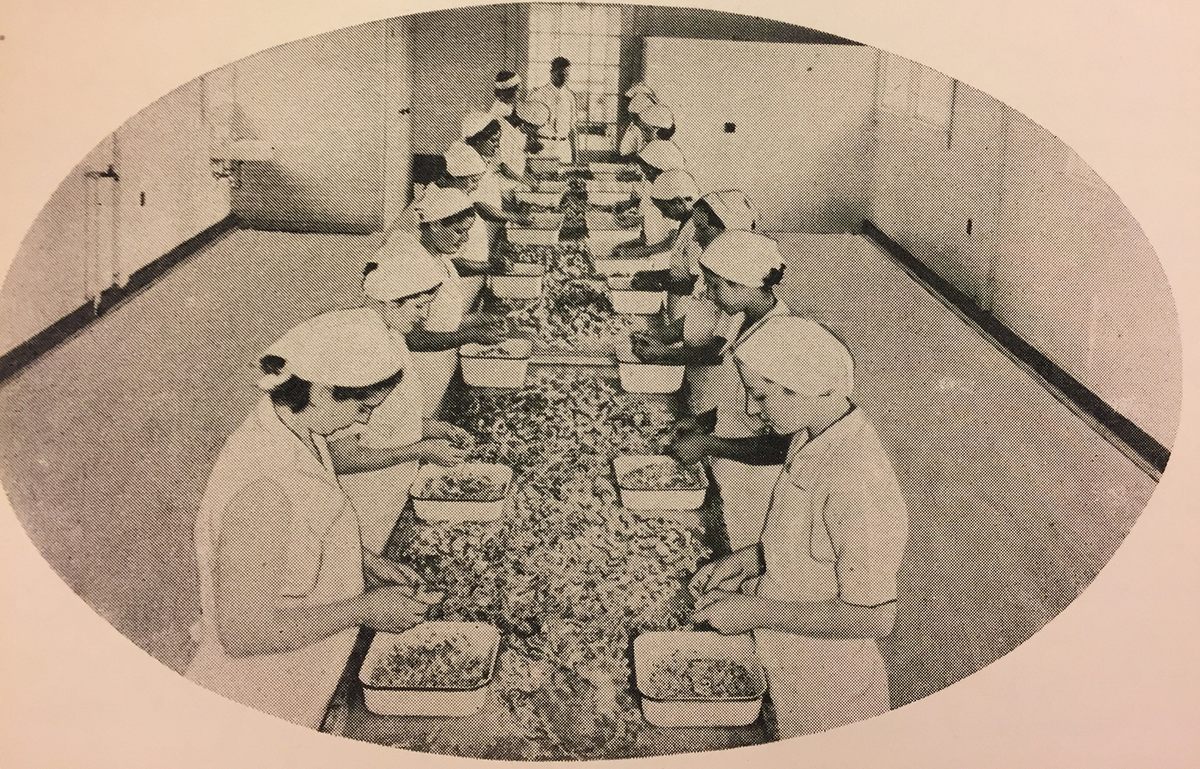

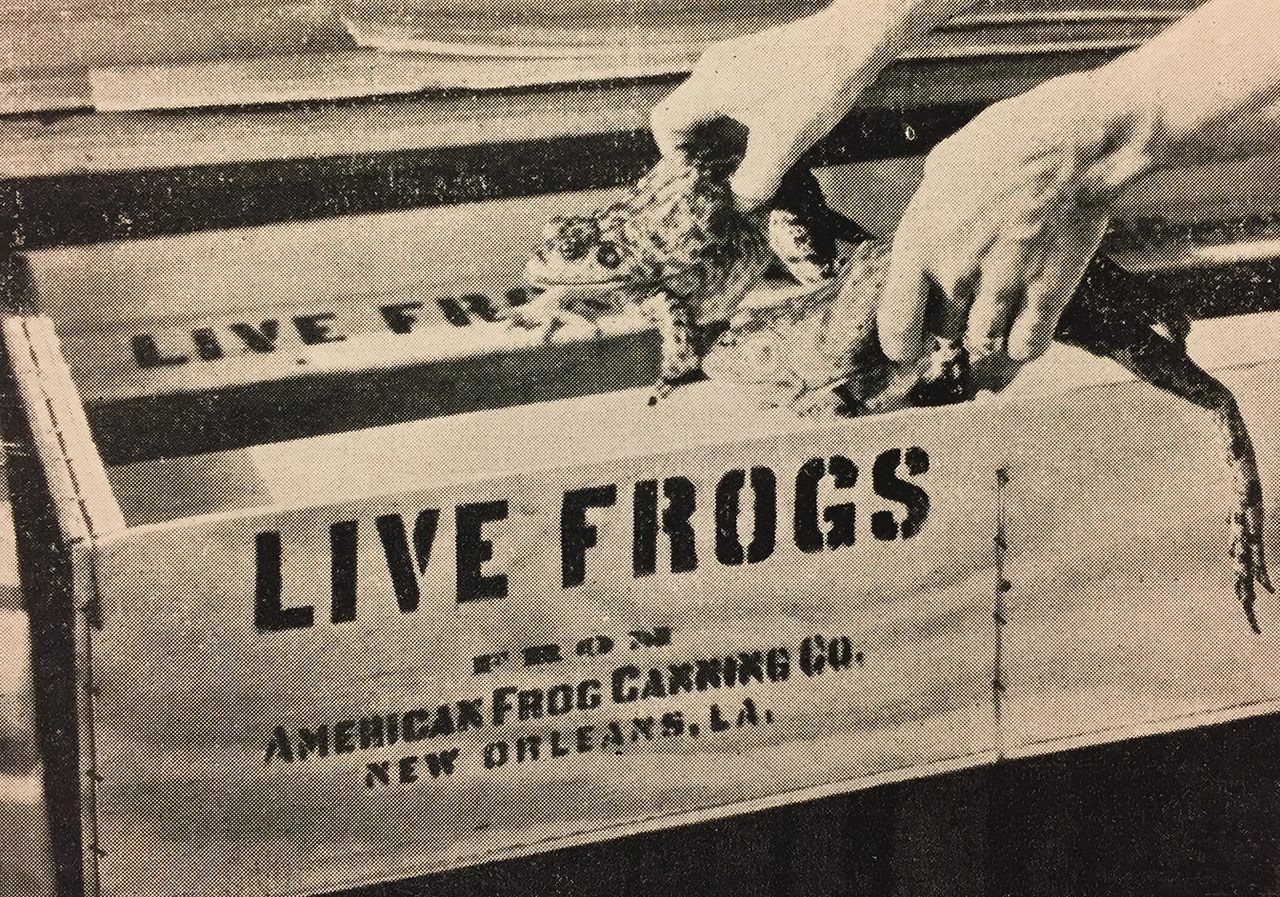

Soon, his business there was growing so rapidly that, he wrote, “my own frog farm and the supply of wild frogs brought in by hunters could not possibly keep the plant in operation.” He started running ads, like the one above, and soon frogs were being delivered to the factory from all over the country.

Broel was on the leading edge of what The New Yorker once called “the frog-farm craze of the thirties.” Newspapers across the country mentioned of the numerous letters they’d received asking for more information about raising frogs, and shared stories about frog entrepreneurs, from “society women” in Tennessee to a Japanese frog-raiser in Los Angeles. After Louisiana, Florida had perhaps the next most ambitious frog-farming operations. One, Southern Industries Inc., offered shares to northern investors in order to expand more quickly.

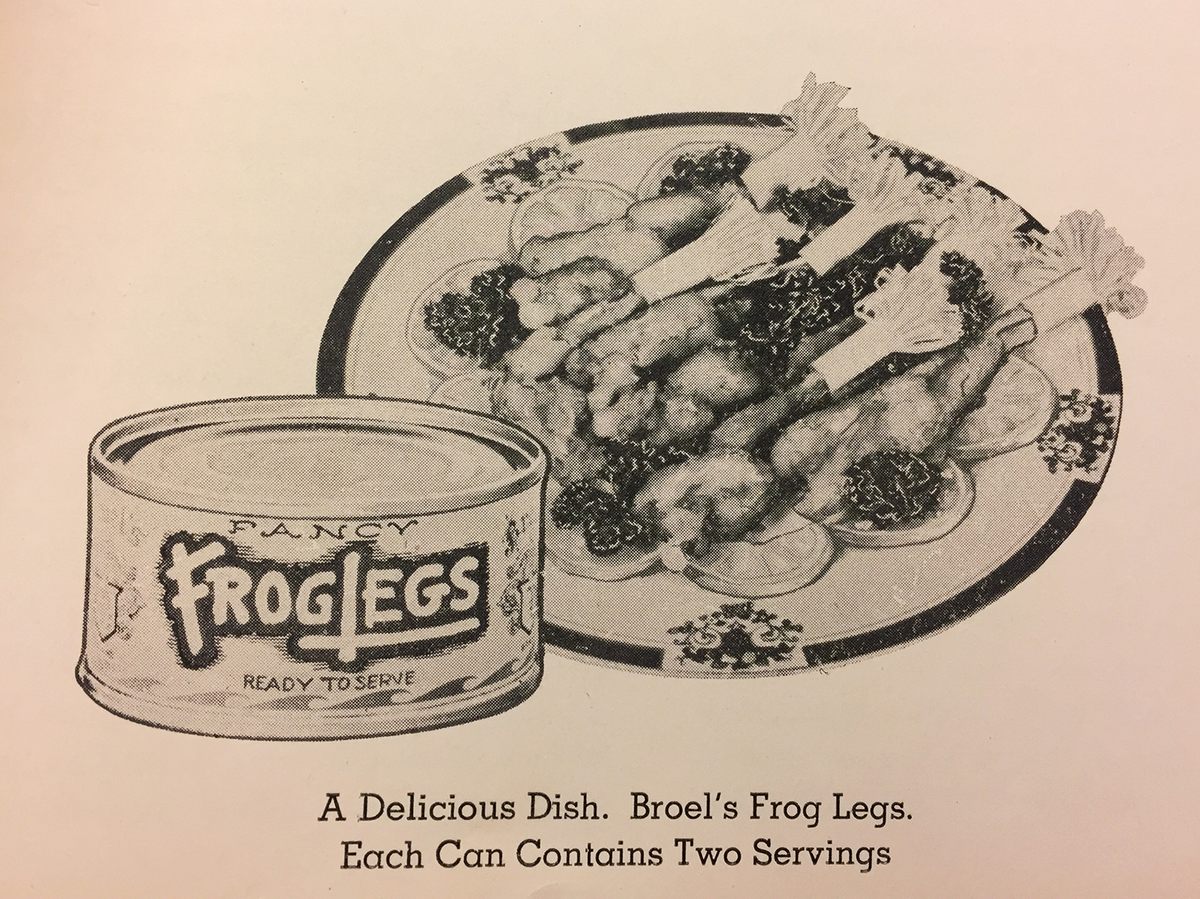

Among all these frog-minded people, Broel was a giant, “the nation’s largest individual producer of frog legs,” the Central Press reported, and a genius promoter of his product. He canned frog legs and “frog à la king,” and dreamed up recipes for Giant Frog Gumbo, American Giant Bullfrog Pie, Barbecued Giant Bullfrog Sandwiches, Giant Bullfrog Omelet, Giant Bullfrog Pineapple Salad, and more.

As the craze grew, though, so did skepticism about the frog business. The industry, the Los Angeles Times wrote, was “somewhat ephemeral.” A Midwest paper compared it to rabbit farming, another get-rich-quick scheme meant to harness the reproductive potential of small food animals. In 1933, the USDA released a bulletin on frog farming that warned, “Within the past fifteen years the bureau has received thousands of inquiries concerning frog raising, but to the present time it has heard of only about three persons or institutions claiming any degree of success.”

That was a far cry from what Broel’s ads and other promotions promised, and in the mid-1930s, the U.S. Postal Service indicted him for mail fraud. “Frog Breeders Leap with Cash,” one newspaper gleefully reported. Broel and a partner had “hopped to New Orleans,” as another reporter put it, after cashing $15,000 worth of checks for instructional brochures.

One of the most egregious claims he’d published was that in 13 years, a man could make $360 billion growing frogs. “I assume it is needless to tell you that I made no such statement,” Broel wrote to one Ohio paper. Someone else had made the calculation, and Broel hadn’t meant to endorse its truth. It was “simply published as I publish all other things of interest to people engage in the frog business,” he wrote. “I think you will agree with me that such a statement is so ridiculous upon its face that it could not seriously influence the judgment of anyone deliberating as to whether or not he should engage in frog raising.”

But people had bought into the hype. Around the same time, one of the other frog-farm success stories, Southern Industries, was facing lawsuits from its investors, who had been promised big returns. After one year, they had still received no money, and demanded to know “why they had received no dividends on their investment in pairs of frogs.”

One of the major points Broel made in his case for frog farming is that frogs are delicious. In the wild, “everyone” wants to eat frogs, he wrote: snakes, birds, lizards, fish, even hedgehogs. And that intense pressure from predators is the reason for their incredible rates of procreation. A single frog has to lay 10,000 to 20,000 eggs just to have a few of its offspring survive. Tadpoles are born to be disposable.

That’s one of the first problems facing a frog farmer. Most of those potentially profitable, would-be frogs die before reaching marketable size. Fungal diseases can wipe out thousands of frogs in a single season. And as the frogs grow, they have to be protected from hungry predators of all kinds—starting with their own parents. If frog farmers don’t whisk tadpoles away to separate ponds, hungry adult frogs will make meals of them.

Frogs eat a lot, and yet another challenge is keeping adult frogs fed. It takes about one pound of food to grow one-third of a pound of frog meat. Frogs have only one requirement for their meals, but it’s one that makes keeping them on farms very hard. Whatever they eat, whether insects, tiny crabs, or crawfish, has to be moving. “Production of live feed becomes a full-time activity in any frog farming operation,” one government pamphlet warns.

All this work has to go on for years before a frog farmer sees any profit. Whereas chickens, for example, can be raised and slaughtered in months, bullfrogs take two to three years to reach marketable size.

Even Broel didn’t depend on farmed frogs to feed his canning business. “We buy frogs!” announced a sign outside the company headquarters. Many of his suppliers weren’t farmers at all, but frog hunters who waded into the swamps of Louisiana, where it could be possible to catch 100 frogs in a few hours.

Frog hunting was so popular that the state’s population of wild frogs was declining, though. In his book, Broel used this as a selling point for potential frog farmers, but ultimately it proved the demise of his business. By the end of the 1930s, Louisiana had passed a law restricting the hunting of frogs in the high season, April and May. Cut off from a supply of wild frogs—a void that farming could not fill—Broel shut his canning company down.

“That’s really what put Daddy out of business,” says Bonnie Broel. “I know that he was not able to get enough frogs to maintain the business, even with the demand there was for it.”

The American dream of frog farming didn’t die with the craze of the 1930s, though. Even after shutting down the canning factory, Broel kept selling “breeder” frogs. He didn’t grow them anymore, says Bonnie Broel, but rather worked more as a frog middleman.

“We knew if there were brown bags in the fridge, there were frogs in there,” kept in a state of hibernation, she says. “If I couldn’t take a bath, there were frogs in the bathtub, and he would be feeding them live goldfish.”

Decades later, during the 1970s and ’80s, the back-to-the-land movement bred another generation of would-be frog farmers, led by Leonard Slabaugh, owner of Missouri’s Slabaugh Frog Farms. “Supermarket chains and wholesale outlets buy ‘em in enormous quantities. Big restaurants want ‘em shipped out on ice. People come by here and pick ‘em up by the buckets full,” Slabaugh told a reporter for Mother Earth News. “Why, the market is growing continuously all the time.”

Among all the misleading hype of frog farming, this was a core truth. All over the world, people love to eat frogs, and by the end of the last decade, the international market in frog meat was worth about $40 million.

Starting the 1980s, frog farming started growing in Europe, Brazil, and Southeast Asia. Research has improved techniques for raising frogs in artificial ponds, keeping them disease-free, and even convincing them to eat feed pellets or dead insects. (These techniques often involve mechanical swishing of dead insects in water, so that they appear alive.)

And yet, most frog meat sold around the world today still comes from wild populations, which are being hunted down at alarming rates. By 1980, France had so few frogs left that it banned commercial harvesting altogether. After that, India and Bangladesh became the main sources of frog meat for export—until the populations there shrank and new regulations grew.

Now Indonesia is one of the world’s main suppliers of frog meat, and scientists suspect the population there is in danger, too. One recent study found that out of more than 200 samples of commercially available frog meat, only one matched the frog species listed on the label, a commonly sold species, indicating that perhaps this species’ populations had crashed and hunters had moved on to others.

Another group of scientists found that about 200 million frogs are being exported each year, predominantly from Indonesia and China to the European Union and the United States. Factoring in local consumption, a rough estimate puts the number of frogs being taken from the wild each year at around a billion.

As India and Bangladesh discovered, this scale of harvesting leads to larger ecological impacts. Take away frogs’ enormous appetite for live insects, and bug populations boom. Those two countries restricted frog hunting in part because they foresaw a pest problem of plague-like proportions.

“If you look at frogs as a commodity, their dollar value is pretty small,” says Ian Warkentin, one of the biologists who has studied frog markets. “But if you look at the ecological role they are playing, to financially replace all those creatures that are eating insects, it has value that’s way beyond its commercial potential.”

Commercial farming always involves a type of artifice, since it tries to corral and improve upon the foods found out in the wild world. Successful crops are not necessarily the tastiest or the most desirable, but are often the plants and animals that bend most readily to our will, at a profit. Frogs have resisted that sort of control, but our taste for them is strong enough that we still go after them. If anyone does eventually figure out an efficient new way to raise giant frogs for pleasure and profit, perhaps they will finally claim the fortune that Broel imagined.

We’re launching a food section! Gastro Obscura will cover the world’s most wondrous food and drink. Sign up for our weekly email to get an early look.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook