We’re Hardly Using Any of Our Fossils

The vast majority are languishing in museum storage. Is it time to dig them up all over again?

Imagine: The year is 1918, and you’re walking on the beach in California when you stub your toe. You look down to see what you’ve hit, and you notice that it’s not an ordinary rock—it’s a fossil, perhaps some sort of prehistoric snail. You dig it up, clean it off, carefully write down where and when you found it, and donate it to your local museum, as you have been taught. This is to be your contribution to history, to the scientific record. In your most hopeful moments, you picture your fossil providing vital information to a scientist, or on careful display in a glass case, delighting visiting children.

Now fast forward a century. Your specimen is neither changing minds nor on display. Instead, it’s hidden away in a drawer in an offsite storage facility, along with your handwritten index card. No one has looked at it in decades. In a way, it needs to be dug up all over again.

According to a recent study, such is the fate of nearly all the fossils ever found. “There are enormous amounts of data sitting in various museum collections,” says Peter Roopnarine, the curator of geology at the California Academy of Sciences and one of the authors of the paper, which was published last month in Biology Letters. “Our picture of what’s going on is based on whatever small fraction we manage to study, and publish upon.”

For the study, Roopnarine and his co-authors quantified this fraction across nine different institutions in California, Washington and Oregon. They calculated that of all the specimens housed in these collections, more than 95 percent are from locations that have never been written about. Extrapolating their findings globally, they predict that “perhaps only 3–4% of recorded fossil localities are currently accounted for” in published literature.

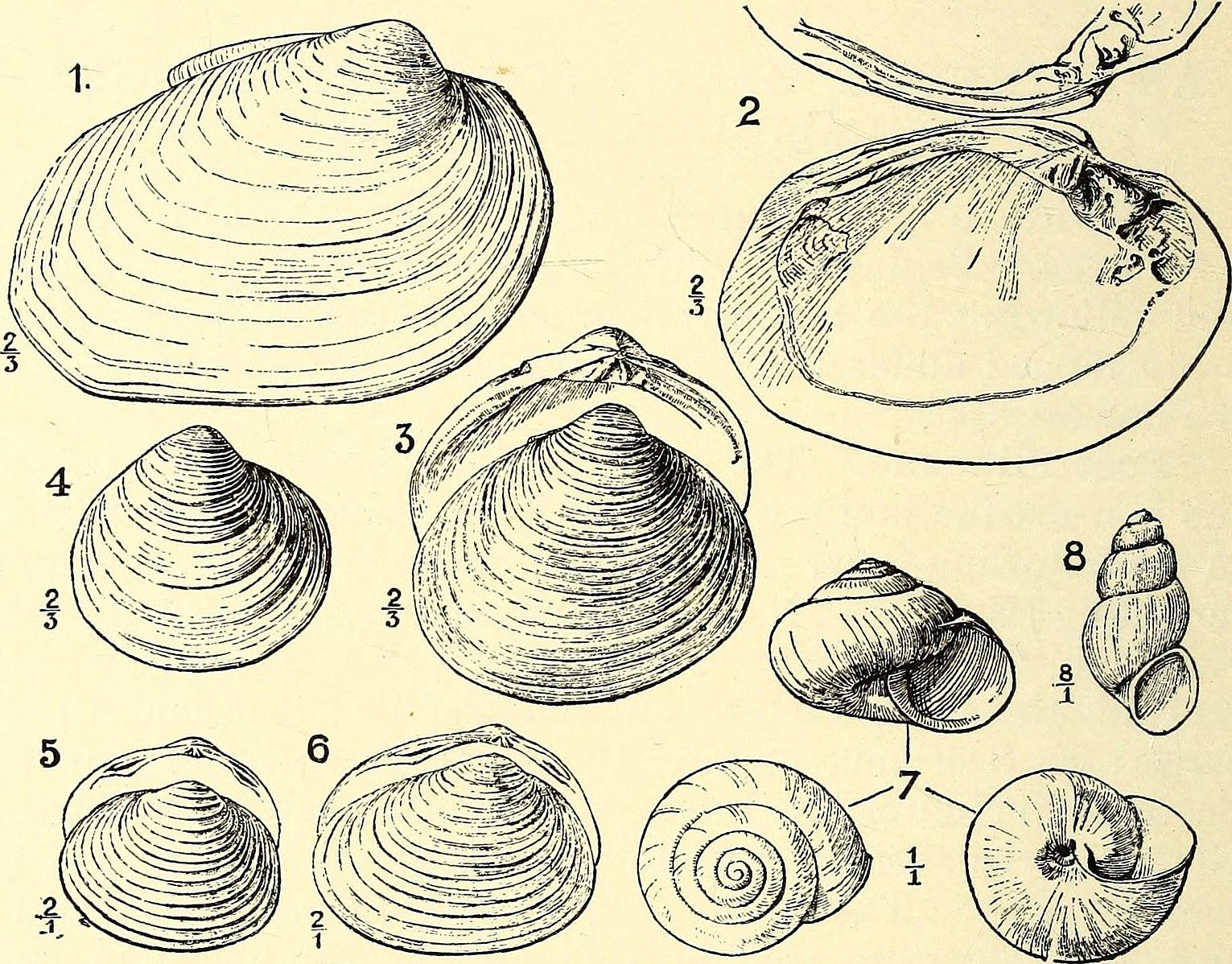

In the process, they also set out to change that, committing themselves to digitally documenting a particular subset of all of their specimens: Marine invertebrates found in the Eastern Pacific that are 66 million years old or younger. Each crab, clam, cockle and cowrie is getting its age, identity, and location put online, and some are being photographed and scanned as well. The resulting database—called Eastern Pacific Invertebrate Communities of the Cenozoic, or EPICC—is growing every day.

Petrified ocean critters may seem like a strange candidate for digitization, but there are many reasons to put them online. One is that it helps researchers get a more comprehensive idea of whatever it is they’re trying to study. As the new paper details, for past generations, taking any kind of long view required painstakingly compiling information by hand. It’s probably no accident that the geologist John Phillips—who, in 1841, made the first published attempt at a geological time scale—began his career in the discipline by organizing museum fossil collections.

In the 1980s, Roopnarine says, paleobiologists began undertaking even more in-depth literature reviews. It was at that point, he says, that “we began to discover ways to approach questions we hadn’t before.” In 1982, for example, two geologists trawled through nearly 400 papers and databases of marine fossils, and managed to pinpoint the five mass extinction events Earth has experienced since life first formed. “The advantages of accessing big data became very obvious,” says Roopnarine.

Online databases like EPICC make this kind of thing even easier. The compilers’ goal is to “allow any researcher to be able to reconstruct the history of this region from whatever perspective they’re coming from,” and study anything from food webs to species movements to the effects of climate change, Roopnarine says.

Another reason is to hedge against disasters. The loss of a specimen is tragic no matter what, but if you have information about it—its species and location, or even better, a photograph or scan—“at least we know what existed,” says Roopnarine. After Brazil’s Museu Nacional burned down in early September, several groups put out calls for images, scans, or 3D models that people might have taken of its holdings. A large number of its natural history documents are also available online, previously digitized by the museum.

Institutions in the American West are particularly aware of this danger, says Roopnarine: “We are absolutely paranoid about fire here.” The California Academy of Sciences burned down in 1906, after the San Francisco earthquake. Before the blaze, it had housed the second-largest natural history collection in the country; by the time the flames snuffed out, it had lost 25,000 taxidermied birds, most of its entomology and herpetology holdings, and its entire library. (Alice Eastwood, the curator of botany, saved over a thousand plant specimens by bundling them together and lowering them from the sixth floor to the ground with ropes.)

“If the tragedy in Rio tells us anything, it’s that you never have a good forecast of how much time you have to do this. And we need to do it sooner rather than later,” says Roopnarine. “Unless you make these efforts to distribute [data], to back it up… this story’s going to be told over and over.”

Last but not least, you simply find neat things. “Every now and then we come across a gem of a specimen,” says Roopnarine of getting his own department’s fossils in order. The other day, they found the shell of a predatory snail that had been eaten by one of its peers. Inside was a fossilized hermit crab, who had taken up residence there. “I don’t know what the deep scientific value of that is going to be,” he says, “except it’s awfully cool.” Somewhere, maybe, its discoverer is smiling.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook