The Sad Tale of the ‘Flying Tailor’

Franz Reichelt’s devotion to developing a parachute suit led to his dramatic death.

Poor Franz Reichelt. He had one dream: to create a working parachute suit. But as he tragically found, when you’re a tailor with nothing more than early 20th-century technology at your disposal, even a straightforward dream can turn deadly.

The history of the parachute goes back centuries, with inventors mainly focusing on improving and perfecting variations of the same life-saving fabric canopies we still use today. Reichelt, however, saw a different path. Born in Austria, Reichelt moved to Paris in 1898, at the age of 19. A tailor by trade, he opened a successful dressmaking business in the center of the city that catered to Austrians visiting Paris. But by the early 20th century, he’d begun to dream of a more utilitarian garment.

The world of aviation was being tested and expanded at a steady clip around the turn of the 20th century, leading to such milestones as the Wright brothers’ famous first flight in 1903. Amid all that adventurous experimentation came a number of tragic accidents, like the death of Germany’s “Glider King” in 1896, and the case of Thomas Selfridge, the first person to die in a powered-plane crash in 1908. Reichelt got it in his head to do something to help improve the safety of these early aviators. Thus was born his vision of the parachute suit.

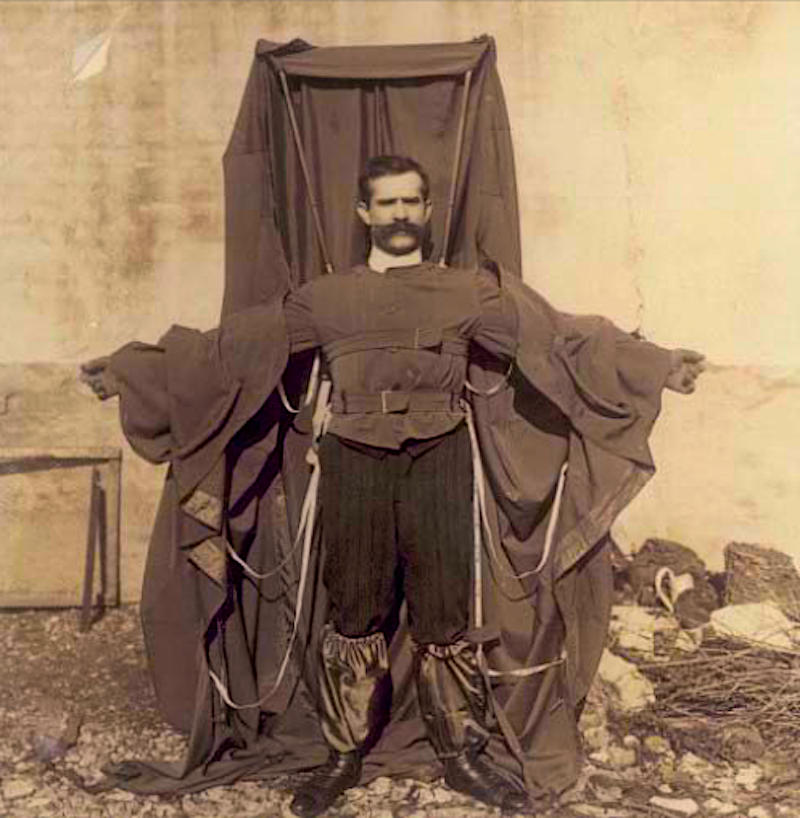

Like all parachutes, his idea relied on the increasing the surface area of a falling person in an attempt to slow their descent, but instead of being attached to an overhead canopy, his parachute would be integrated into the flight suit itself.

The beauty of Reichelt’s potential suit was that it would be lightweight, and not hinder the wearer’s movement. Not unlike a shaggy version of the daredevil wingsuits we have today, Reichelt’s suit had a number of extra panels and flaps that would deploy as a person was in freefall. Or at least that was the idea.

Reichelt’s experiments with the parachute suit began around the summer of 1910. He saw some early success with a winged suit that supposedly carried a weighted dummy from the fifth floor to the ground with a gentle landing. However, subsequent suit designs failed to prove his concept, as more dummies thrown from the roof of his dress shop crashed down into the courtyard in what would have been a fatal drop for a real person. According to a story in the French daily paper, Le Matin, published in 1912, Reichelt even presented his idea to the country’s leading aviation organization of the day, Aéro-Club de France. Roughly translated from the article, they told him: “The surface of your device is too weak, you will break your neck.”

Determined to prove that his parachute suit would work, Reichelt continued to refine and test his design. He even began to test the suits himself in 1911, with one jump from a window over 26 feet off the ground resulting in a broken leg. Even with multiple failures, Reichelt remained convinced of his suit’s efficacy, reasoning the only problem was that the drop distance was too short for the flaps to deploy properly.

A reward had been offered through the Aéro-Club de France for anyone that could develop a superior parachute design, which Reichelt was convinced he had. In 1912, he arranged to stage a highly publicized demonstration of his suit in which he would jump off the first deck of the Eiffel Tower, over 180 feet up.

Even back then, the authorities weren’t too keen on letting a someone leap from a landmark in an experimental parachute, so Reichelt obtained permission to perform his demonstration on the understanding that it would not be him, but another mannequin, in the suit. This, however, was never his plan.

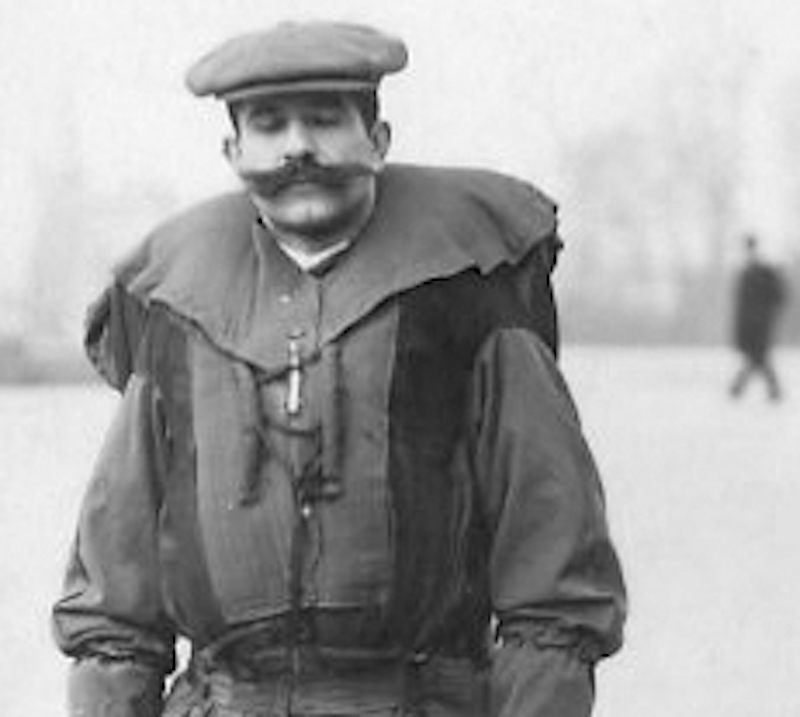

The event took place on Sunday, February 4, 1912. Reichelt arrived at the Eiffel Tower on that chilly morning already wearing his parachute suit, peacocking for the 30-some writers, photographers, and other press who had gathered for the demonstration.

After showing off his suit a little bit, Reichelt ascended to the first stage of the tower, finally making it clear to all assembled that he planned to make the jump himself, convinced that the weight of his body and added height would make the suit work correctly. His friends and attendants tried to dissuade him from jumping, or to call the event off due to the wind and cold. But Reichelt was immovable. As can be seen in a grainy period recording of the event, Reichelt climbed on a stool placed on a table to raise him over the guardrail, and prepared to jump. He stood poised on the rail for over 40 excruciating seconds, before diving off the edge.

Reichelt’s suit failed to deploy correctly, seeming to wrap and tangle around him, turning him into a torpedo. He plummeted straight down and perished instantly. This was also caught on film. (The British Pathé film archive has posted the footage online—before watching, note that it includes the moment of impact.)

The next day, a number of French newspapers reported on the grim event, describing the gut-sinking moment when onlookers knew something was wrong, and the mangled mess of brown cloth and broken bones left in the aftermath. According to a 1912 article in Popular Mechanics, “Reichelt dropped like a stone.”

Today, Reichelt’s story is usually presented as a sort of punchline about the hubris of inventors, earning him the nickname, the “Flying Tailor.” His story appears in books with titles like The Darwin Awards, The Little Book of Big F*#k Ups, and The Mammoth Book of Losers. However, even though it might seem foolish in hindsight, if Reichelt’s invention had worked, his story would likely be heralded as a tale of bravery in the name of innovation.

Before jumping to his death, Reichelt shouted, “See you soon!” Unfortunately gravity had other plans.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook