Unveiling the Mystery of a Royal Wedding Dress Lost for 179 Years

Made famous by ‘The Empress’ on Netflix, Sisi and her missing garment provoked an imperial hunt over centuries.

After Austrian Empress Elisabeth married Emperor Franz Joseph in Vienna in 1854, her wedding dress disappeared. Commonly known as Sisi, the Empress has long been quite the celebrity in Europe. Her rebellious nature has been depicted in films like Corsage and the chart-topping Netflix series The Empress. Yet, despite her popularity, Empress Sisi’s wedding dress has been veiled in secrecy for almost 200 years. Now, thanks to a series of clues, Austrian researcher Dr. Monica Kurzel-Runtscheiner may have solved the ancient sartorial puzzle.

Knowledge of this dress has always been hidden. That’s because journalists, illustrators, or anyone who could chronicle the event were banned from the Imperial wedding. With no confirmed images or detailed descriptions of the gown, the dress became a mystery. One trace remained: a lavish dress train, believed to have been attached to the Empress’ wedding gown. This train is on display in Vienna’s Imperial Carriage Museum, of which Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner is the director.

Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner has been called the “huntress of the lost treasure,” and it’s a nickname she’s taken to. She’s investigated this particular case for years, trawling library archives in search of answers, but without much luck.

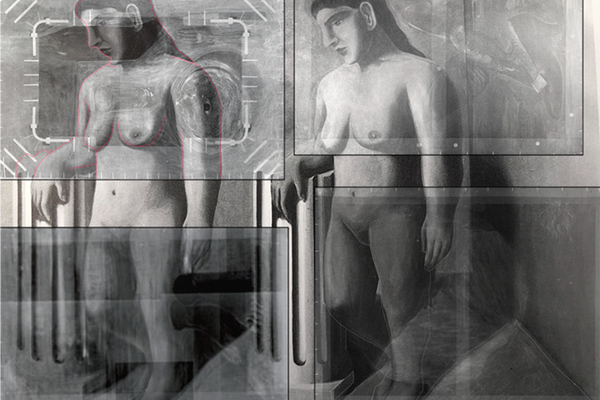

Then, in 2021, a breakthrough arrived. Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner received a tantalizing message. She was contacted by a stranger, Spanish freelance researcher Silvia Santibañez, who told her she’d found an obscure 1857 portrait of Elisabeth at the Silesian Museum in Opava, Czech Republic. In this painting, Sisi is wearing a wedding dress, including the train from the museum in Vienna.

“I was thrilled,” says Dr Kurzel-Runtscheiner. “I finally had proof, other than family tradition, that Sisi actually wore our train at the time of her wedding. Moreover, it showed what the accompanying dress looked like, which previously could only be speculated on.”

Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner spent months decoding this painting, seeking confirmation it truly portrayed Sisi’s vanished dress. The 1857 portrait was unusual for two key reasons. Firstly, it was painted three years after the wedding. Secondly, it was not done by an Imperial court artist, as was tradition, but by a painter named Joseph Neugebauer. This could lead some people to believe the painting was not authentic. “But he shows the dress in such detail that he must have seen it—there is no other [painting, description, or] representation of the dress he could have used,” Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner says.

But Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner didn’t end there—she wanted to make sure everyone could see the dress. So she put together a team.

First, she traveled to the Silesian Museum with photographers, who captured high-resolution images of the 1857 portrait. Then graphic designers at her Vienna museum used those photos, as well as the original dress train, to create a pattern repeat of Sisi’s gown.

“This enabled us to link the pattern visible in the painting to the embroidered structure of the preserved train,” Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner explains.

After months, her team then located someone who could print the pattern onto fabric: a man in Bavaria, Germany, who ran a small printing shop. They sent samples back and forth between Vienna and Bavaria until the fabric print was almost perfect. Then came a major setback.

“The German printer became seriously ill, and it seemed like the project would fail at the last moment,” she says. Though Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner says he has since recovered, she explains, “We owe him a great debt of gratitude for agreeing to print the fabrics for us the weekend before he went to the hospital.”

Next, they took the fabric to a restorer in Vienna, who made—by hand—a full-sized replica of the dress.

The recreated dress, along with the original 1857 portrait of Sisi wearing the dress, are on display at the Imperial Carriage Museum in Vienna until November 5, after which they’ll decide which museum will receive it next. This is the first time the public can see two versions of what she believes may be Sisi’s gown.

All of this has unraveled at a perfect time, according to Maura Hametz, Professor of History at James Madison University in Virginia and co-author of Sisi’s World: The Empress Elisabeth in Memory and Myth. She says Sisi’s tale has entered new levels in the mainstream due to the Netflix drama series focused on her life. The Empress has proved so successful that it was instantly renewed for a second season.

“[This] has attracted significant attention from audiences, particularly in the U.S., who were largely unaware of her,” Professor Hametz says. “The thing about Sisi is the intrigue—the glamor and enduring charisma of the empress—and the dress embodies this fascination.”

Sisi’s recreated wedding dress is “the most accurate reconstruction of the original gown based upon the limited visual resources available,” according to Olivia Gruber Florek, Associate Professor of Art History at Delaware County Community College and author of The Celebrity Monarch: Empress Elisabeth and the Modern Female Portrait.

Taking the sleuthing even further, Florek says researchers can now use clues within the 1857 portrait to try to identify the gown’s designer and the source of its materials. “Wedding gowns are often an opportunity to promote national industries—Queen Victoria’s gown was only made from British materials, for example—so there may be records of its production,” said Florek.

Despite all this, Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner won’t yet promise her work is finished. Her next move is to visit monasteries in Hungary and Bavaria to examine artifacts said to be linked to the wedding gown. For now, Sisi’s riddle persists. “The probability is 50%,” says Dr. Kurzel-Runtscheiner about the likelihood that the garment she recreated is the Empress’s missing dress. “If I was sure, I wouldn’t call it a mystery dress.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook