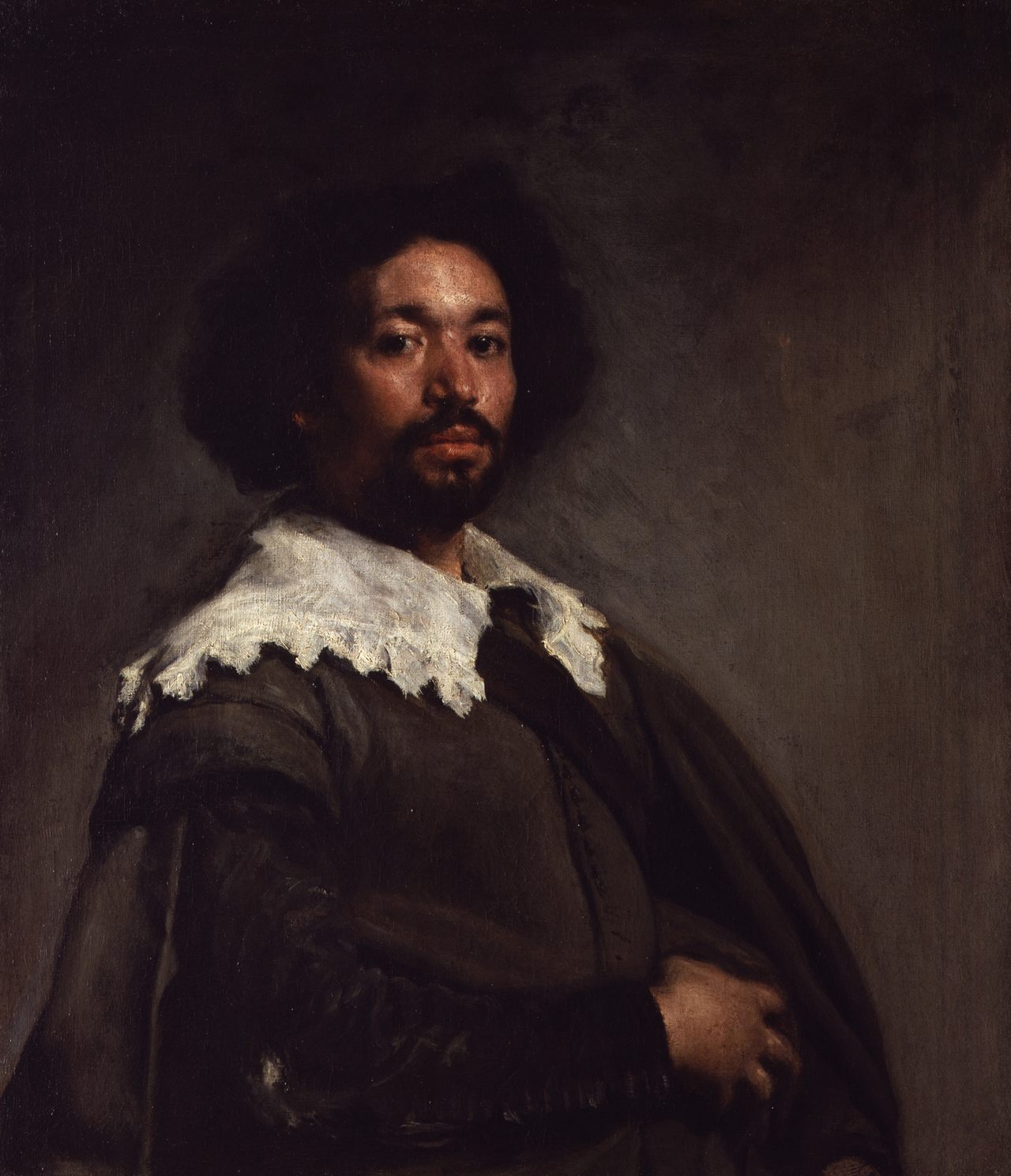

This Was One of the Most Famous Faces of the 17th Century

But we’re only starting to learn the facts of artist Juan de Pareja’s life.

In 1971, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art announced its triumphant acquisition of a masterpiece by the 17th-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. Purchased at auction from a British aristocrat for $5.5 million (roughly $40 million today), the luminous, life-sized Portrait of Juan de Pareja had long been admired for the way the Baroque superstar captured his sitter’s quiet nobility in a few deft brushstrokes. It was said that when Velázquez unveiled the painting beside its flesh-and-blood subject, people couldn’t tell which face was more real.

But while Portrait of Juan de Pareja may be one of Western art’s most captivating canvases, Pareja himself has turned out to be even more intriguing. Enslaved by Velázquez for decades, Pareja was also a talented artist in his own right, one whose story complicates what we know about Spain’s Golden Age and the very history of painting. And that story is finally being told by the Met with a new exhibition, Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter.

Over the five decades since it first went on view in New York, Velázquez’s portrait of Pareja has remained a consistent crowd-pleaser. But by 2019, when curator David Pullins arrived at the Met, the time felt right for a reappraisal.

“I think there was definitely the sense that this painting needed to have its moment of attention,” says Pullins, who co-curated the show with Vanessa K. Valdés, a professor of Spanish and Portuguese at New York’s City College. “But it was always going to be a question of on whom the attention landed.”

In its rough outlines, Pareja’s story has long been known: Born into slavery around 1608, most likely in Spain, he is connected with the Velázquez household in historical documents from the 1630s, although it’s unclear whether Velázquez purchased or inherited him. In any case, for a successful Spanish artist to own slaves was not uncommon, especially in Seville, where as many as 15 percent of residents were enslaved or recently freed, most (but not all) of them of African descent.

Pareja would have worked in Velázquez’ studio, preparing canvases, grinding pigments, cleaning brushes—and apparently honing his own artistic eye. By 1648, the ambitious Velázquez had become a favorite of King Philip IV, who sent the painter to Rome with orders to acquire artwork and plaster casts of classical sculptures to bring back to Madrid. Velázquez took the opportunity to tour Italy, and he brought Pareja with him, along the way painting his slave’s famous portrait. The canvas was included in an important 1650 exhibition at Rome’s Pantheon, where—according to the Flemish painter Andreas Schmidt—it stole the show: “[I]n the opinion of all the painters of different nations everything else looked like painting, this alone looked like truth.”

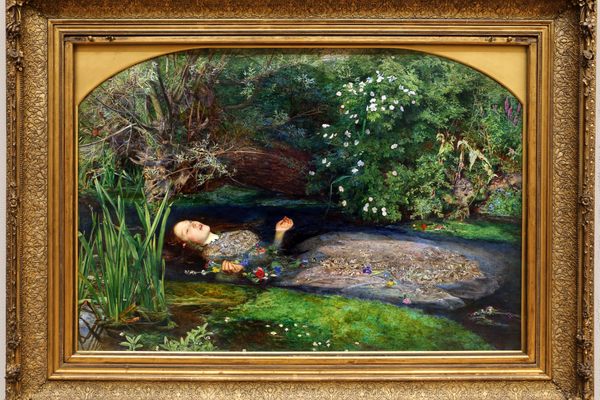

The portrait also seems to have won celebrity for Pareja, which may have contributed to his change in fortune: Nine months after painting his portrait, Velázquez signed papers that promised Pareja his freedom in four years. Pareja lived another two decades, during which he made his own living painting court portraits and religious scenes, including The Calling of Saint Matthew (1661), which includes a full-length self-portrait of the artist staring boldly at the viewer. On loan from the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, it takes pride of place at the Met’s new show.

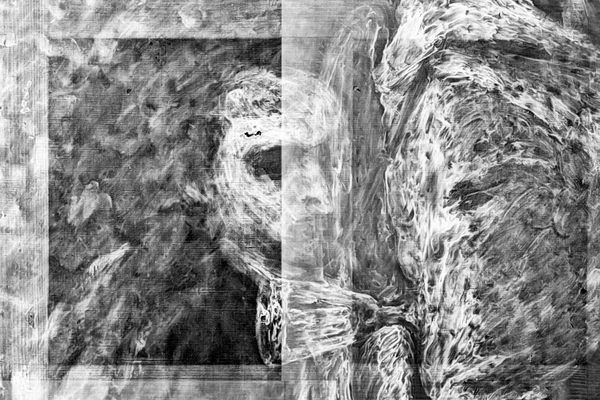

Assembling the exhibition, which features loaned canvases by Pareja and his contemporaries along with historical artifacts that include Pareja’s actual manumission papers, was a challenge. But adding context proved at least as difficult.

“Accepting ambiguity is par for the course where it comes to working on peoples of African descent, particularly in the early modern period,” Valdés explains. “For those of us who work in this field, we accept that there’s much that is not known, and we are actively reconstituting people’s lives and the cultures and the societies in which they lived.”

Pullins and Valdés wound up relying heavily on long overlooked scholarship by Arturo Schomburg, the historian and Harlem Renaissance figure, who traveled to Seville in 1926 to research Pareja and his milieu. (“These are questions that have been asked before,” Pullins notes. “They just were not being asked in this building.”) Still, much of what had been written on the artist over the centuries has proved dubious, as patchy documentation provided fertile ground for legend-making.

“A lot of just completely fantastical, made-up information was circulating about him,” Pullins says, noting that one biographer claimed without evidence that Pareja died in a duel. Even after pruning the mythology away, the exhibition and its accompanying essays do not represent the definitive report, he cautions. “We’ll have to wait for people to pick up the various breadcrumbs that we hoped we’ve left.”

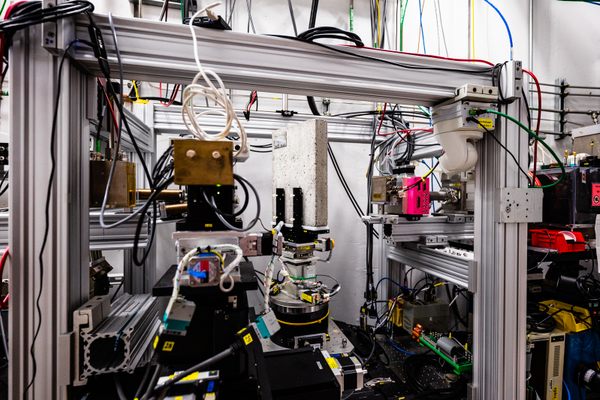

Among the details that remain for future curators and historians to discover are the whereabouts of several Pareja paintings known only from various text references over the centuries, including a miniature version of Pareja’s The Calling of Saint Matthew, reportedly painted on copper.

“We’re in a position now at the Met where we have wonderful support from donors and the institution as a whole to go around to obscure towns and have any work by Pareja photographed in high resolution, in color,” Pullins says. “I think it’s inevitable that from this certain works will turn up.”

The exhibition, in that sense, is the first serious step toward reconstituting an artist’s body of work. But it’s also a step toward creating a more expansive canon of Western art, one that doesn’t discard an icon like Velázquez, but which also acknowledges the full humanity of a man, and fellow artist, whom he both enslaved in life and immortalized on canvas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook