Eat Like Vikings and Other Ancient Seafarers

Options included lutefisk, porridge, and a surprisingly tasty salsa.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE JULY 15, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

When Christopher Columbus bumbled his way into the Bahamas in 1492, his crew must have been relieved—if only for a break from leathery salted beef and hardtack biscuits softened in water-flavored wine. On a later voyage, Columbus’s son Ferdinand wrote, “What with the heat and dampness, our ship biscuit had become so wormy that, God help me, I saw many who waited for darkness to eat porridge made of it, that they might not see the maggots.”

In 1519, when Ferdinand Magellan vowed to circumnavigate the Earth on a two-year voyage with five ships and 239 men, he set forth with 2,626 kilos of aged bacon, 1,547 liters of dried beans, 1,293 kilos of cheese, 140 barrels of anchovies, 207 kilos of dried fish, and 73 kilos of rice, plus three live pigs and six live cows. The survivors came back with reports of eating rats.

Throughout human history, ships have often been the driving force of exploration, warfare, immigration, and trade. And everyone, from ancient Roman galley rowers to Viking marauders, had to eat. We’ve come a long way from pots of gruel to cruise ships that serve 30,000 meals a day.

The options over the millennia have ranged from grim to downright luxurious—Chartreuse jelly, anyone?—and tell us a lot about their respective time periods. What was on the menus had an enormous impact on how far voyagers could travel—and how many would live to tell the tale.

Gastro Obscura spoke with Simon Spalding, the author of Food at Sea: Shipboard Cuisine from Ancient to Modern Times about the evolution of onboard dining.

Q&A With Simon Spalding

Let’s start with the good. What historical ship’s recipes turned out to be surprisingly tasty

In the 13th-century Catalan-Aragonese fleet, the men received biscotti—ship’s biscuits. They were the ancestors of our modern biscotti, even if they were not quite as tasty as the ones that we dip in coffee today.

Their hot food was salsa, which is different from the salsa that we have in Mexican restaurants today. It’s quite an old word in the Mediterranean for some stuff all cooked together.

The ingredients included garbanzo beans and onions and a tiny bit of meat. That was one of the surprises, that what galley rowers were eating in the mid-13th century was something I thought was quite tasty.

What was one of the worst examples you came across?

There was an 18th-century French ship’s cookbook that included recipes for bills, rats, and seabirds. Those were described as desperation recipes.

If you had absolutely nothing to eat, you could maybe keep your crew alive with these. And while I did test most of the recipes in my book, I did not test my recipes for rat and seagull.

I also wrote about how terrible the food situation was for immigrant ships in the mid-19th century, where they were expected to bring their own food. By the time of the great famine in Ireland, these ships stocked cornmeal, which the Irish called yellow meal, for them to cook into mush.

So each family has to vie with other ones for access to one stove that’s lashed to the deck that they could only use in daylight hours and fair weather. If they had no other food, that would have meant for the, say, five weeks for passage from Ireland to the United States, they were eating nothing but cornmeal.

When did crossing the Atlantic start to get less hellish?

Moving forward to, say, 1910, things are much better. For one thing, steam engines become more efficient. By the 1880s, you have steam ships carrying immigrants where all the food is being prepared centrally, it’s being served, it’s included in the price of their ticket.

What about when you get to more luxurious ocean liners like the Titanic?

The Titanic is handy because it’s been so well documented. I thought it was interesting because the first- and second-class meals were all coming out of the same galley. The soup, for example, would be the same broth for both classes. They’d just have something more expensive floating in the first-class version.

But the more profitable part of the business [of these kinds of ocean liners] was carrying third-class passengers because there were more of them.

It was interesting for me to find, looking at the White Star Line that owned the Titanic, their third-class offerings include a lot of very hearty fare, but you can see there’s a different orientation.

For example, the meal cards were written in English, German, Swedish, and Finnish, whereas the second-class menus are all in English. First-class menus are in English with many French words in them.

Something else I found interesting was this meal card that said that kosher meals were available on request. Consider that after 1900, you’ve got pogroms going on throughout the Russian Empire. So you’ve got lots of Ashkenazi Jewish people who are desperate to get out of where they’re living, and many of them, as we know from American history, end up traveling by steamer and arriving in Ellis Island.

What do we know about some of the earliest seafarers?

A lot of our information about the ancient world comes from shipwrecks. There’s evidence of people transporting goods in the Stone Age and we have dugout vessels from that early as well.

So that first model where people are traveling in a dugout canoe, you can be pretty sure any food they’re eating is food that they brought with them.

There’s the model that most people are familiar with, which is where you actually have cooking facilities onboard. In the Mediterranean, they developed onboard cooking facilities much, much earlier, at least by 600.

Then there’s another model, which is very important to understand if you’re looking at the ancient world. In northern Europe, there are a lot of islands where there’s no trees growing, so in some cases they’re even bringing firewood with them. And they’re going ashore to do their cooking. Looking at Homer’s Odyssey, it looks like that’s what they were doing.

Is that what, say, the Vikings were doing?

People ask, “Were they cooking on these Viking ships?” Well, an open wooden boat with tarred rigging is highly inflammable.

There’s no evidence of onboard cooking at all. So you’re dependent on driftwood or firewood that you carry with you in order to be able to go ashore and make a fire.

One thing that they cooked was a kind of porridge or barley meal, which doesn’t sound very exciting, but if you’ve been eating cold food for days and days, a bowl of hot barley meal porridge would have been a treat.

What was the onboard Viking porridge alternative?

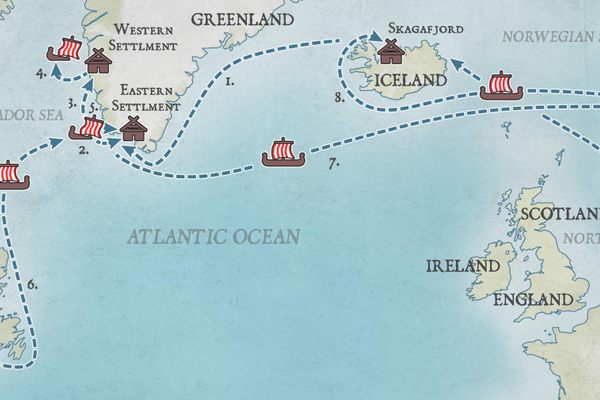

Lutefisk starts off as stockfish, or air-dried cod, which was a product of Iceland after the Vikings had settled it already.

When these medieval Scandinavians settled in Iceland, they had this wonderful confluence of resources. They’re in the middle of the North Atlantic, surrounded by cod, which is a virtually fat-free fish, which makes it a good candidate for preservation.

I went to Iceland once in January of 1988. My travel agent asked if I’d lost my mind. When the wind blows from the north, you can tell it’s coming right off the polar ice cap, and it’s just penetrating, cold wind.

Hilmar Hauksson, my host at the time, said with this broad, Icelandic smile, “The only thing between us and the North Pole is wind.”

But that was a resource for the early Scandinavian settlers of Iceland, because what they could do was take cod and hang the filets in drying sheds.

That became a staple for all of Europe. All of Christian Europe ate fish on Fridays. Just as Greenland became the source for walrus ivory, Iceland became the source for stockfish. Their whole economy was based on the export of this one item.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook