The Dinner That Kicked Off the First Dinosaur Craze

One of the world’s first life-size dinosaur models was the venue.

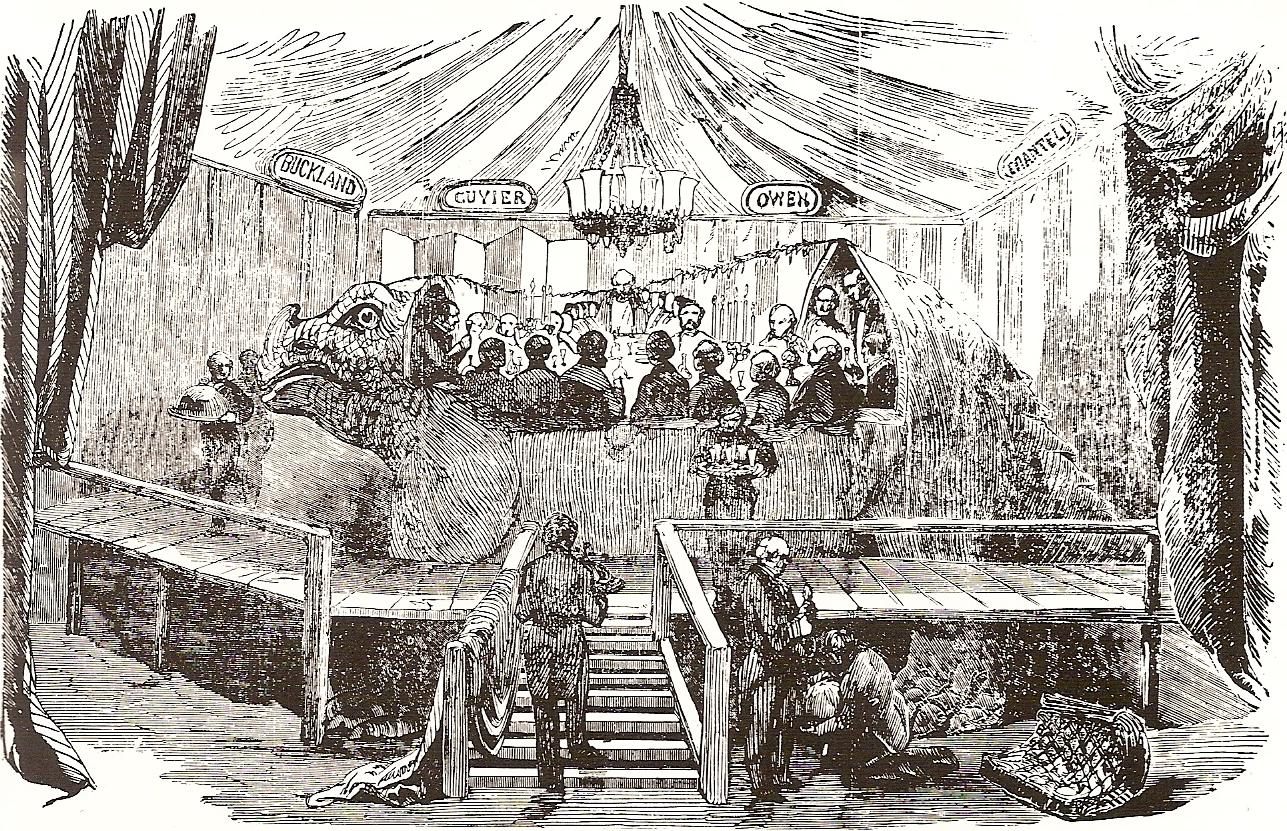

On New Year’s Eve in 1853, a group of scientists, businessmen, and newspapermen sat down to dinner inside a life-size iguanodon model. It was one of the first reconstructions of a dinosaur ever made, and the dinner was a publicity stunt that helped launch an incredibly successful craze: our obsession with dinosaurs.

By the time of the dinner, scientists had found and studied fossils for millennia. But dinosaurs didn’t yet have today’s grip on the public imagination. Even the word “dinosaur” was new—invented by one of the dinner’s attendees in 1842.

Richard Owen was a paleontology pioneer and the dinner’s guest of honor. Trained as a doctor, he spent much of his career researching fossils. He also advised artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins on the design of 33 concrete dinosaur models, including a certain iguanodon. The Crystal Palace Company had commissioned the statues to accompany the reopening of the Crystal Palace, a massive structure of glass, steel, and iron that had been erected for an international exhibition and then laboriously moved nine miles away.

The British public had seen prints and drawings of dinosaurs, but not full-sized replicas. The Crystal Palace Company made a savvy bet that the models would draw a crowd to the Crystal Palace. The dinner in the iguanodon, hosted by Waterhouse Hawkins, was part of this effort. The iguanodon model was thirty feet long, and guests lined its open back cavity. Reports varied as to how many people could fit inside, and whether or not the dinner took place in the dinosaur statue itself, or in the mold that the concrete was poured into. Either way, it helped garner interest in the dinosaur-filled re-opening.

In a drawing published in the Illustrated London News a week later, the iguanodon is surrounded by a tall stage that helped guests and waiters climb inside. Guests enjoyed seven lavish courses, starting with mock turtle, hare, or vegetable soup. The main course options included mutton cutlets with tomato, partridge stew, curried rabbit, and filets of sole with mayonnaise. The scientists must have had iguanodon-sized sweet tooths, as waiters served French pastries, jellies, puddings, fresh fruit, and nuts for dessert.

The dinner was a success, drawing media attention and stoking excitement for the reopening. Punch, a famous humor magazine at the time, joked that if the guests had lived in the era of dinosaurs, they likely would have ended up as dinner themselves.

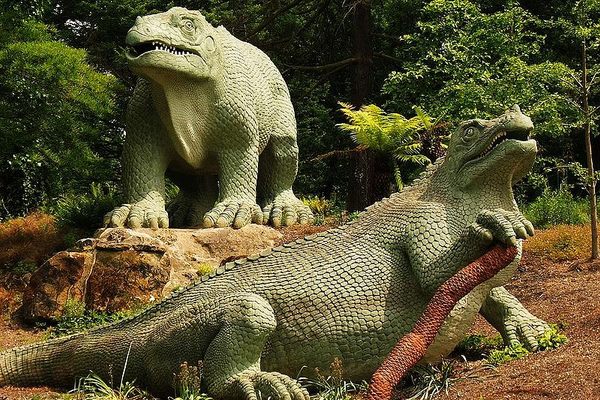

The two iguanodons as well as the megalosaurus, plesiosaurs, and others were a smash hit. The public snapped up posters and figurines depicting the models, and over the next half-century, more than a million people a year went to gaze at the dinosaurs. As dinosaurs leapt off the page and into real life and a theme-park atmosphere, paleontology went from a stuffy, academic topic to a subject of fascination.

Though you can still see the famous iguanodon model at Crystal Palace Park, it likely doesn’t resemble an actual iguanodon. One of Owen’s academic rivals, Gideon Mantell (or, as legend has it, his wife) actually discovered the iguanodon, and his studies correctly determined that it was partially bipedal.

Mantell refused to advise Waterhouse Hawkins on the models, though, due to ill health and wariness over the commercial nature of the project. Owen, who believed the iguanodon to be a rhino-like quadrupedal creature, was tapped instead. Mantell died in 1853, missing the dinner entirely. But without his work, there would have been no iguanodon to serve as a party venue, and perhaps no dinosaur craze either.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook