Every January, This City in Ecuador Fills With Dancing Devils

Diablada de Píllaro is a rebellious but festive answer to a much older tradition begun by Spanish colonizers.

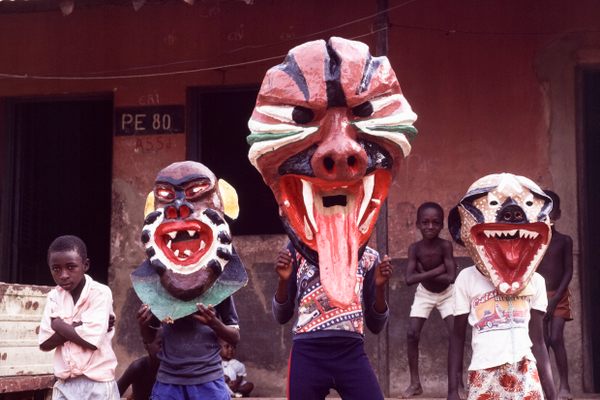

Nestled in Ecuador’s High Andes, more than 9,000 feet above sea level, beside apple orchards and potato fields, is the small city of Píllaro. For most of the year, the sleepy mountain town acts as a quiet backdrop to Llanganates National Park’s stunning mountain vistas. But for the first six days in January every year, devils roam Píllaro’s streets. A live band, featuring trumpets and drums, announces their arrival in the town’s crowded streets. The devils tease and mock as they go, scaring away children with their hand-painted, boldly colored masks. Line dancers known as bailarines de línea follow, wearing beautiful dresses and mesh masks with delicate features. After the parade, the devils return to their homes outside the city to eat their fill of a whole roasted pig and liberal libations. That is, until it’s time for them to march again on Píllaro.

Known as Diablada de Píllaro, this festival has a strong rebellious character. While its origins are under some debate, it’s generally believed to have started under the hacienda system, during the 16th-20th centuries, when European colonizers forced local people to work on their large estates. In one version of events, wealthy landowners in Píllaro ushered in the new year with lavish balls before taking their revelry to the streets, where Indigenous men acted as “bouncers” clearing their way. Eventually, the story goes, the local men began dressing as devils to make their job a little easier.

In post-colonial Ecuador, Diablada’s devil character became increasingly popular as a symbol of rebellion not only against Spanish colonizers but also against the Catholic Church. The parade also includes other characters, such as the fair-skinned, blue-eyed bailarines. In their wire mesh masks and crisp white shirts, the bailarines represent the hacienda system’s wealthy landowners. There’s also the capariche, a person historically from the lower class who was tasked with sweeping the streets for the procession.

All Diablada de Píllaro participants come from rural farming communities outside the city, another subtle expression of rebellion. Founded in 1570 by Spaniard Don Antonio de Clavijo, Píllaro was an early symbol of European expansion in the region. Today, villages surrounding Píllaro, such as Tunguipamba, form mingas—loosely translated from Quechua as a group or collective—to represent their communities loudly and boldly in the city streets during the festival, essentially asserting their right to be in Píllaro, says Colombia-based photographer Yader Guzman, who photographed the festival earlier this month.

“Small little towns have such rich history and rich traditions that a lot of times go overlooked,” says Guzman, who added that even within Ecuador, many people have never heard of the Diablada. But for the people in and around Píllaro, everyone knows that when they hear trumpets in January it can mean only one thing—devils are coming.

Here’s a devil’s-eye view of Diablada de Píllaro.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook