Zooming in on the Microbiome of Some da Vinci Masterpieces

A new study found plenty of bacteria, fungi, and insect remains, but nothing to be alarmed about.

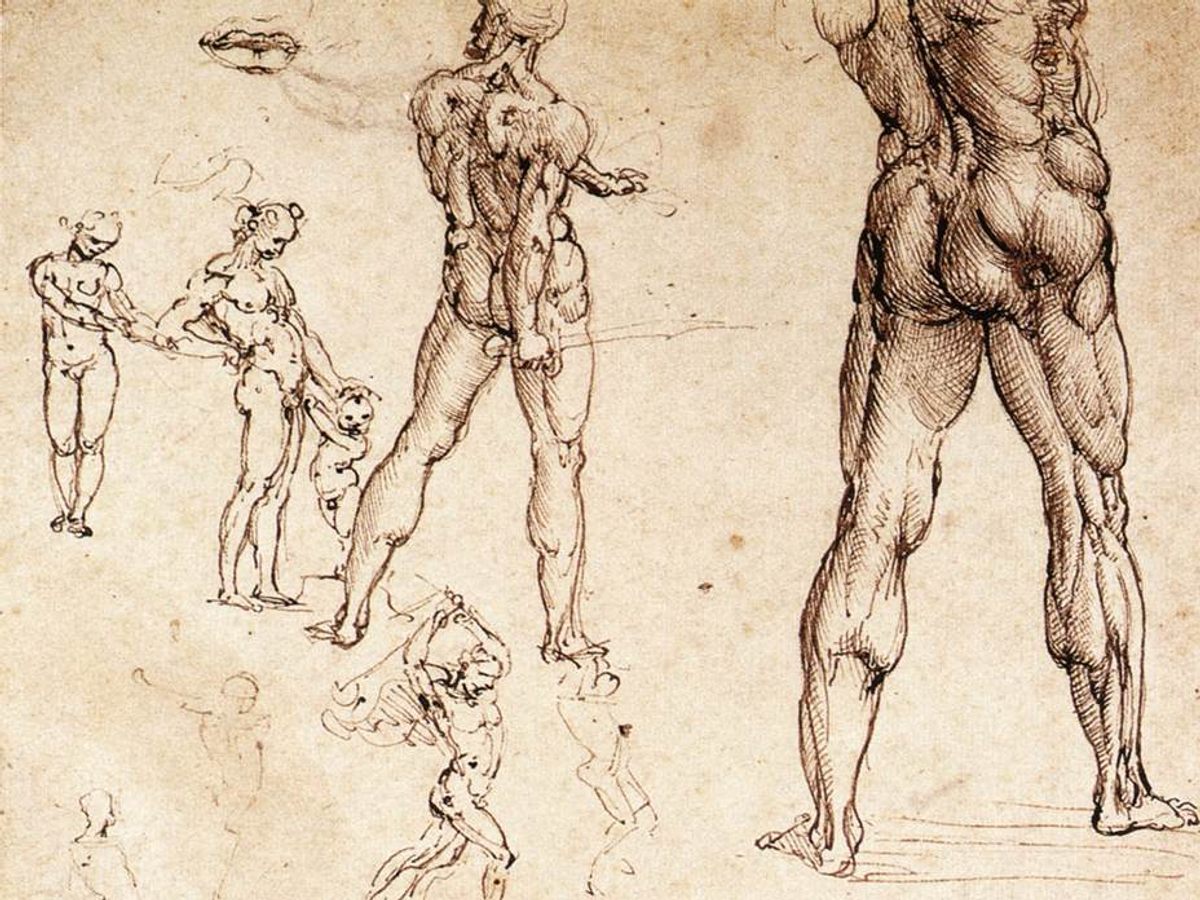

An artistic masterpiece may be timeless, but that doesn’t protect it from time itself. Dust, fungi, bacteria, human DNA: All these and more accumulate, microscopically and sometimes more, on the surfaces of artworks when they’re stored, displayed, or moved outside of ideal conservation conditions. Many works now safely encased in museums still bear scars from centuries of this kind of exposure, even if it is not visible to the naked eye.

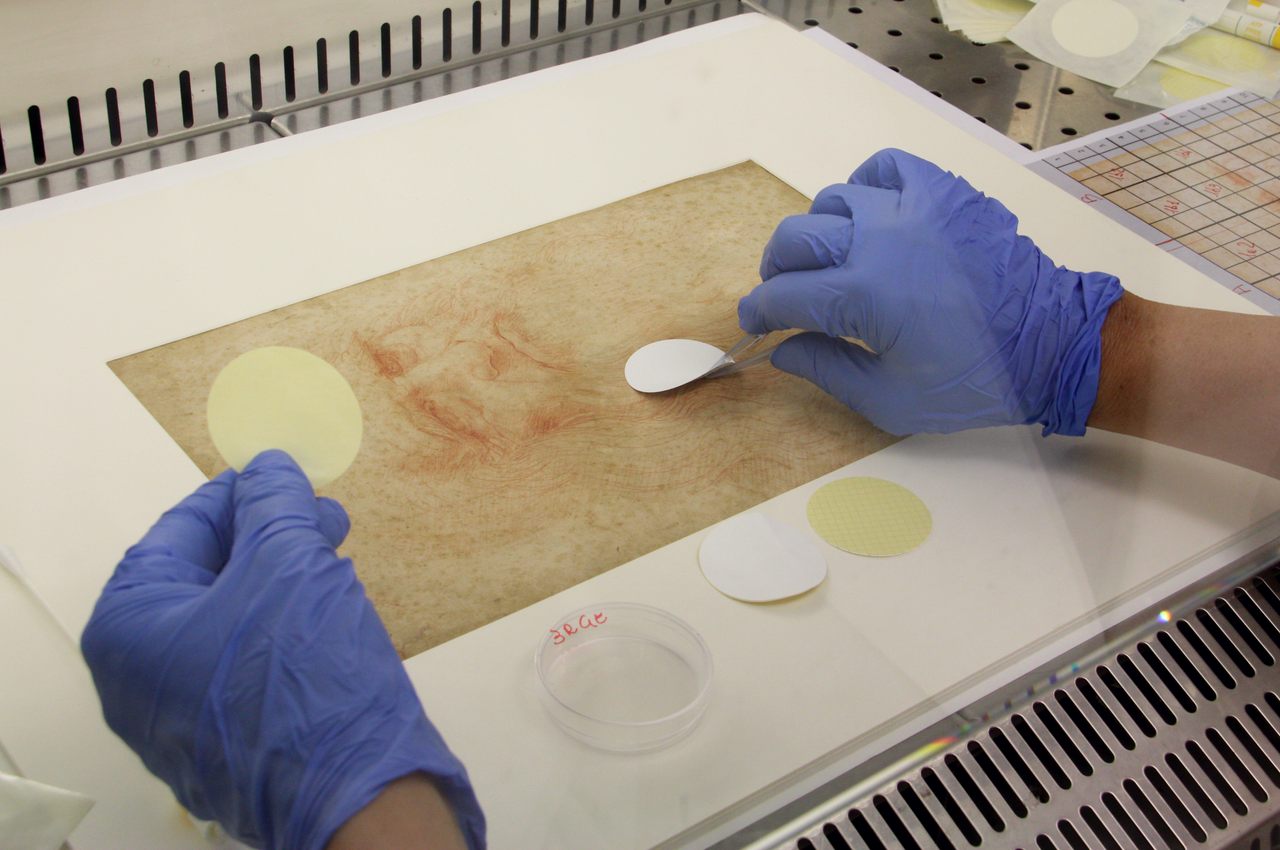

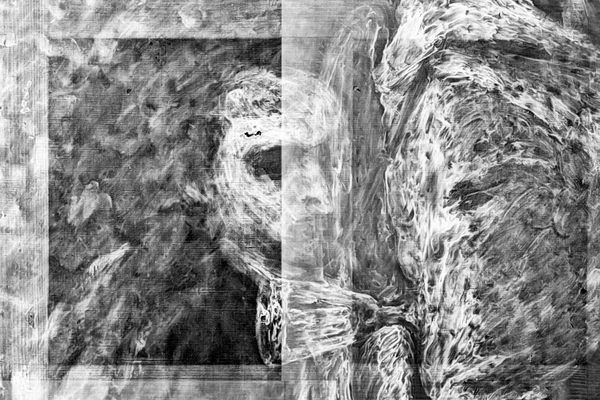

A new study, published in November 2020 in Frontiers in Microbiology, put seven original drawings by Leonardo da Vinci under the microscope to find out what’s clinging to them. Uncovering these drawings’ respective microbiomes, or resident populations of microscopic organisms, can help researchers establish an artistic “bioarchive” to complement other historical records of these and other artworks.

The findings are interesting, if not particularly worrisome for conservators and art lovers. The drawings, from the Royal Library of Turin and Rome’s Corsinian Library, show no visible signs of damage aside from “foxing”—the spotty, brown discoloration typical of aged paper. There were, however, surprises. Researchers note that the “results show a surprising dominance of bacteria over fungi,” despite earlier research indicating that the latter are usually more prevalent on paper. The bacteria observed here are “typical of the human microbiome, introduced by intensive handling of the drawings during restoration works … ” While it’s technically possible that one of those handlers could have been da Vinci himself, lead author Guadalupe Piñar says it’s impossible to know for sure, as no confirmed da Vinci DNA exists in any biodatabase. And it wasn’t just humans with their paws on the master’s work. Researchers also identified material left behind by “insects and their excrements.”

Piñar says that da Vinci’s legendary status could help explain why these drawings have stayed in such good condition, as conservators have had the time and resources to pull out all the stops to keep them safe. She hopes that this research will carry over to other artists, and that microbiome data like this can act as a “control” for before-and-after comparisons following an item’s transfer or movement and handling while out on loan. (Piñar conducted this research while on faculty at Vienna’s University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, but will soon move to a new appointment at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts.) By flagging any new microorganisms that have settled on an artwork’s surface, researchers and conservators can respond to that change as an “alarm,” and treat the piece accordingly, before any possible deterioration from new microbes occurs. The work also serves as a reminder of the underappreciated links and unavoidable co-dependencies between two vastly different disciplines. “Molecular biology is working in art,” says Piñar, just as da Vinci moved between the arts and sciences himself.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook