When Groundhog Was on the Menu in Punxsutawney

From picnics to club dinners, the critter has a long culinary history in Pennsylvania.

Every February 2 since 1887, a groundhog named Phil has made an appearance before a group of tuxedo- and top hat–wearing local gentlemen in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. In earlier decades, the reason the little rodent may have been tempted to dive back into the ground had nothing to do with six more weeks of winter—or Bill Murray having a midlife crisis—but rather with the very legitimate danger that some of the spectators might be planning to eat him.

“There was a time not too long ago when eating groundhog was fairly common throughout rural America,” writes William Woys Weaver in As American as Shoofly Pie: The Foodlore and Fakelore of Pennsylvania Dutch Cuisine. Groundhog dinners were once popular fundraisers among Pennsylvania Dutch communities in the 19th and early 20th centuries, with offerings ranging from roast groundhog with bread stuffing to buttermilk-brined groundhog braised with vinegar and wild ramps.

While part of this affinity was born from resourcefulness, Weaver goes on to insist that there was more to it than that. “Yet properly dressed, groundhog is indeed an underrated American delicacy, and smoked groundhog is an unsung luxury—I do not exaggerate,” he writes. Whether you call them groundhogs, woodchucks, or whistle pigs, the varmints have a mild flavor and texture that Weaver says many have likened to veal.

To anyone horrified by the idea of butchering Punxsutawney’s furry weatherman, it’s worth remembering that it’s no coincidence that the holiday of Groundhog Day originated in this Pennsylvania Dutch stronghold. Grundsau (or “Groundhog”) Lodges were popular gentlemen’s clubs that sprang up around the region in the 1930s. Given that these organizations were often hunting lodges and that Punxsutawney’s first branch sprang up in 1887, it’s not hard to imagine that at that first celebration, Phil—or one of his relatives—may well have been on the menu. In his book Groundhog Day, author Don Yoder cites a 2002 issue of the local magazine Hometown Punxsutawney in which the editor writes that in the past “the groundhog wasn’t the center of attention; he was the center of the meal.”

Since the dead of winter is hardly prime hunting season, members of Punxsutawney’s Groundhog Lodge may have consumed more “groundhog punch”—a questionable-sounding blend of vodka, orange juice, milk, and raw eggs—than actual groundhog. Yet there’s no doubt that locals enjoyed dining on woodchuck well into the last century, particularly during the annual Groundhog Picnic in the summer and early fall. “It is custom for members of the club to take an afternoon off with mattocks and spades and dig up and slaughter a sufficient number of woodchucks for a feast,” reported The Pittsburg Gazette of the town in September 1902. “The animals are cooked by an expert, and while roast woodchuck forms the basis of the feast a variety of other edibles are provided.”

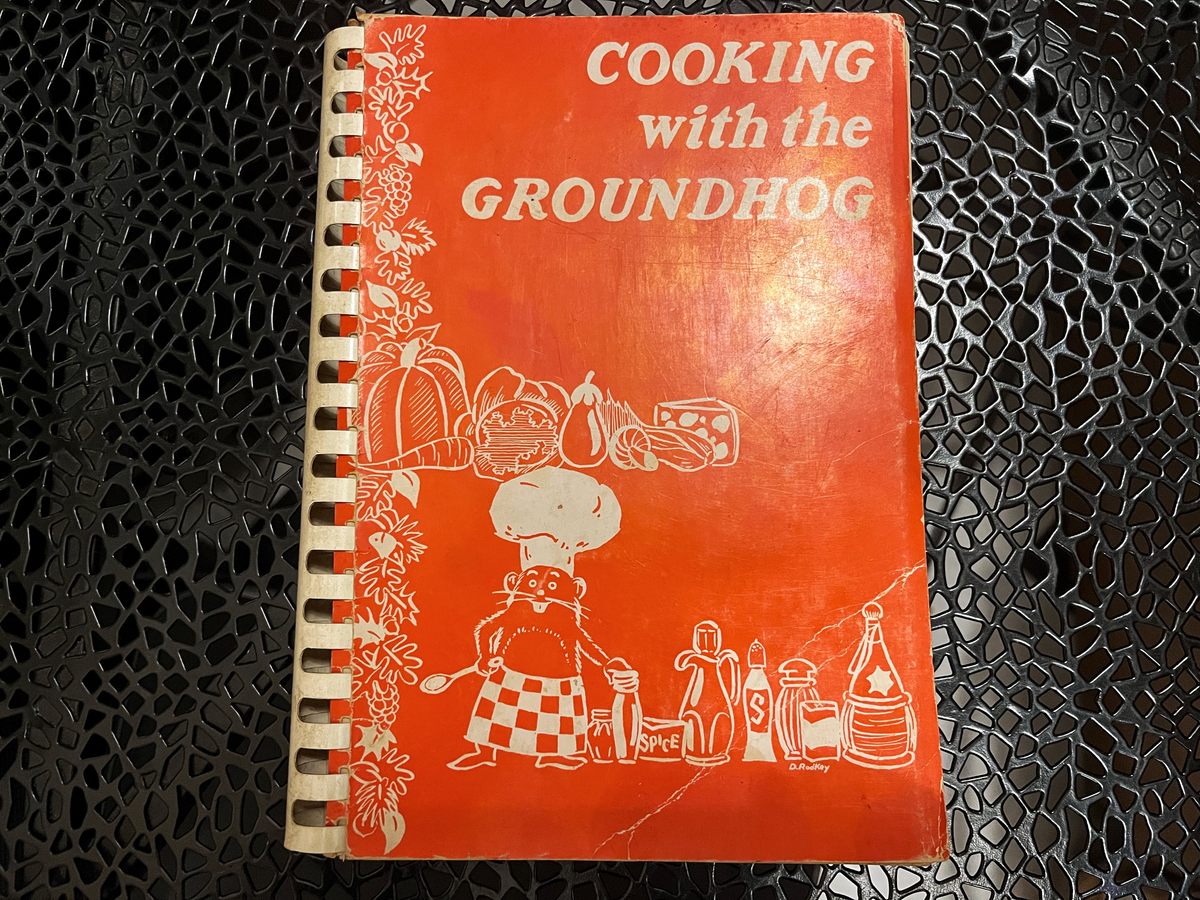

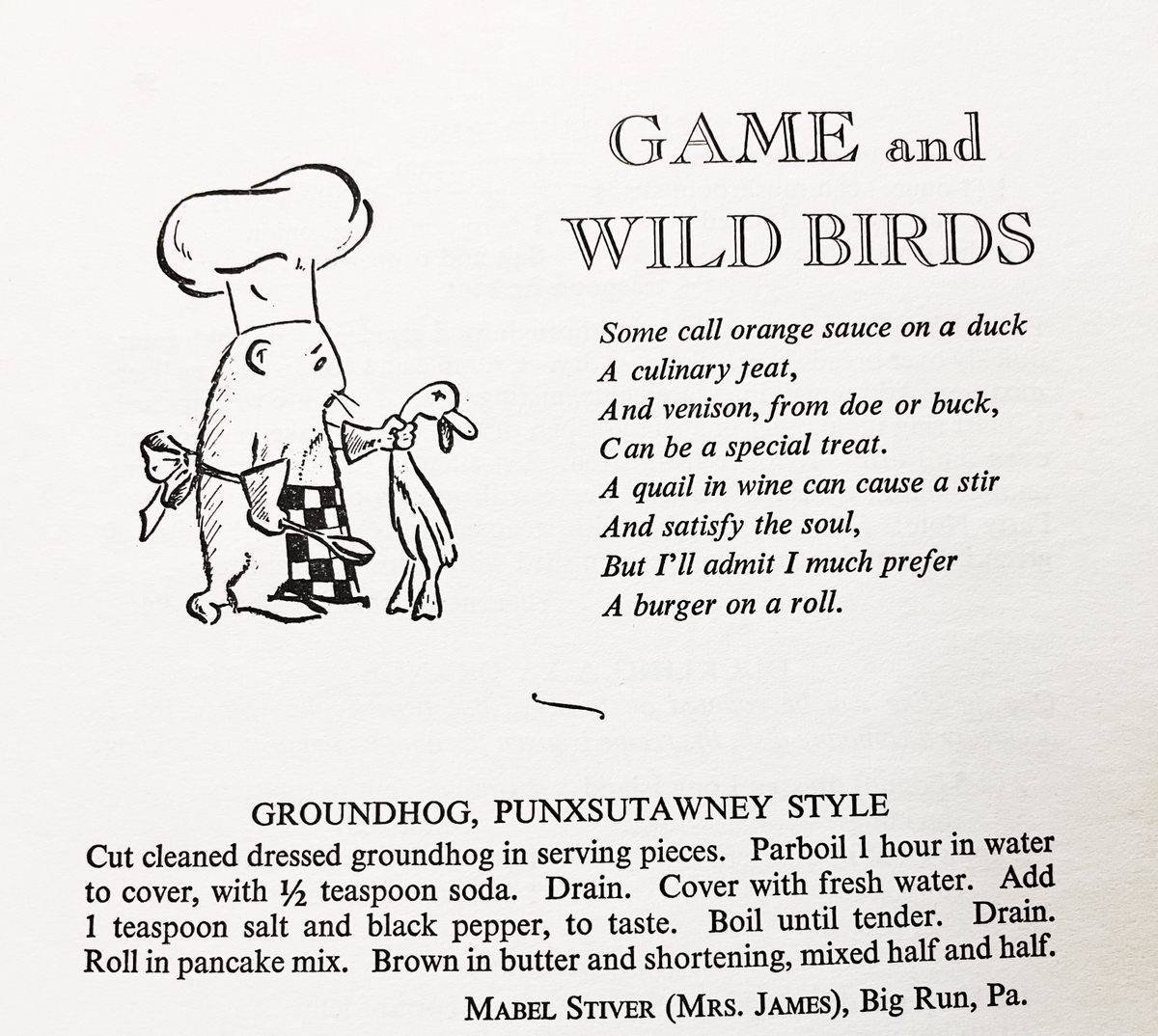

“Groundhog, Punxsutawney Style” is certainly a key recipe in Cooking with the Groundhog, a cookbook published in 1958 to raise money for a hospital in Punxsutawney. Along with an assortment of community-sourced recipes, the book features helpful tips on brining, braising, and otherwise consuming this “clean-living, herb-eating, furry little animal” that makes for “good hunting and good eating.”

In a bizarre twist, the story behind the book feels worthy of its own groundhog-themed rom-com. Elaine Kahn Light, a plucky, young reporter for the Associated Press in Pittsburgh, journeyed to Punxsutawney for Groundhog Day, ended up falling hard for a member of the local Groundhog Lodge, and ditched the big city for small-town life. Light remained an active member of the community until the age of 99. She was particularly fond of the annual groundhog hunt and stag picnic each August, of which she wrote, “The menu hasn’t changed since 1886—barbecued groundhog, corn-on-the-cob and beer.”

Even Light recognizes that readers in other parts of the country might balk at the idea of eating roast woodchuck. “For the uninitiated and the squeamish, properly prepared groundhog tastes very much like rabbit,” she writes. “Some even compare it favorably with lamb and chicken. Prepared with wine and herbs, it becomes a dish for an epicure.”

A whole lot of game animals currently disdained by most American diners—including squirrel, raccoon, groundhog, beaver, possum, and muskrat—were once staples of the country’s cuisine. “We are very disconnected to the food system from the way it was a hundred years ago,” says cookbook author Alan Bergo, also known as the Forager Chef. Recipes for Brunswick stew and other dishes featuring these critters abound in cookbooks from the 1600s through early 1800s. “Small game used to be a major part of the American diet,” Bergo says.

According to Bergo, a former fine-dining chef who has become an advocate for responsible foraging and hunting, we could learn a thing or two from the ways our ancestors ate. Groundhogs are so abundant that most states impose few—if any—hunting restrictions on them. More importantly, relying on groundhogs as a food source instead of, say, pigs or cows, represents a conscientious departure from factory farming.

“You are eating outside of the giant meat-making machine here in the United States,” Bergo says. “It’s a very ethical thing to do, a very sustainable thing to do. You’re not supporting an animal that was raised in cages.”

Bergo catches several groundhogs each year on the farm he shares with his partner using humane Havahart traps. Up until their demise, the groundhogs spend their days nibbling on fruits and vegetables, and living as nature intended. “This was a woodchuck that lived a good woodchuck life,” he says. “They’re sitting [in the trap] eating apples—we put food in there for them. They don’t suffer and we dispatch them quickly.”

Groundhog may be sustainable, but Bergo wouldn’t serve it if he didn’t think the taste was up to scratch. Although game sometimes gets a reputation for being pungent or stringy, as long as woodchucks are correctly prepared, the lean, dark meat is an easy sell. “Groundhog is absolutely excellent,” Bergo says. “It’s like duck crossed with rabbit.”

There’s a straightforward reason for that. Omnivorous or carnivorous animals that feast on rotting meat, fish, or shellfish will tend to taste accordingly. “With the small game, just like any other animal, the taste is from the diet,” Bergo says. “So possum or something that is eating carrion or crayfish is going to have an incredibly strong taste.”

As Michael Twitty writes in The Cooking Gene, resourceful Black cooks in the American South historically would fatten up possums on persimmons. After a week or so on a carefully controlled vegetarian diet, the meat would take on a completely different flavor. Since groundhogs are born vegetarians, cooks can skip this step. “Groundhogs are eating organic produce out of the garden,” Bergo says.

Bergo hopes that in the future, diners will keep an open mind about small game meat—Punxsutawney Phil included. Choosing to eat meat is an inherently complicated issue, but opting out of the meat industrial complex where possible reduces both cruelty and environmental impact. And for those willing to set aside their preconceptions, there’s a real culinary payoff.

“I’ve served people [groundhog] and just told them that it’s small game,” Bergo says. “Everyone has said, ‘This is fantastic.’”

Groundhog Stew With Garden Vegetables

Adapted from a recipe by Alan Bergo on The Forager Chef.

Ingredients

1 skinned and gutted groundhog (2–3 pounds), preferably young, with heart, kidney, and liver

Kosher salt and pepper

1 tablespoon freshly minced rosemary

6 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil, divided, or as needed, plus more for finishing

All-purpose flour as needed for dredging

1 small yellow onion, diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon tomato paste

½ cup dry red wine

4 cups chicken stock

6 ounces mixed baby carrots, zucchini, baby greens, mushrooms, and/or edible flowers for garnish

Instructions

- The night before you plan to serve the stew, cut the gutted groundhog into six pieces using kitchen shears, a very sharp chef’s knife, or a cleaver. Reserve the heart, kidney, and liver and set aside. Carefully remove the pea-sized scent glands, which are located under the skin around the tail, armpits, and back. If not removed, the scent glands can impart an off-flavor to the meat, particularly in older groundhogs. Season all of the groundhog parts and organs liberally with salt, pepper, and rosemary, then cover and allow to dry-brine in the fridge overnight.

- The following day, preheat the oven to 300 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Dredge the groundhog parts (except for the offal) in flour until well coated.

- Heat 2 tablespoons of olive oil in a large Dutch oven until it shimmers. Sear the groundhog pieces in batches until deeply browned, approximately three to four minutes per side. Add additional oil as needed. Remove the groundhog from the Dutch oven and set aside.

- Add another tablespoon of olive oil if necessary, then add onions to the Dutch oven and sauté until they’re softened and beginning to brown. Add the garlic and sauté for one minute, or just until fragrant and beginning to turn golden. Add the tomato paste and stir continuously for another minute, or until the tomato paste caramelizes slightly.

How to butcher and carve up a groundhog. Courtesy of Alan Bergo

- Increase the heat to medium-high and add the red wine. Stir constantly to deglaze the pan, scraping up all of the browned and caramelized bits. Allow the wine to reduce by half, then add all of the chicken stock.

- Return the groundhog pieces to the mixture, then bring everything to a gentle simmer. Place the pot in the preheated oven. Cook for 1.5 hours, or until the meat is tender and falling off the bone. Remove from the oven and allow to fully cool.

- While the meat and braising liquid cool, prep your garnish. Ideally, you want a mix of quick-cooking, garden-fresh vegetables. Evenly dice tender carrots or zucchini, halve or quarter mushrooms, and tear or chop tender greens and herbs into small pieces. Set them aside.

- Once the meat is cool enough to handle, remove the groundhog pieces and carefully pull the meat off the bones. Try to leave the meat in large chunks, if possible. Carefully remove and discard all of the bones, some of which will be small.

- Return the groundhog meat to the braising liquid and gently begin to reheat the mixture, covered, over medium-low heat. Taste and adjust flavor by adding salt or pepper if necessary.

- In a pan, heat one tablespoon of olive oil over medium-high heat, then sauté the mixed vegetables until just cooked. Remove from the skillet and set aside.

- Coarsely dice the groundhog organ meat and season with salt and pepper. Add an additional tablespoon of olive oil to the skillet, increase heat to high, then sauté the offal until fully cooked through and beginning to crisp.

- To serve, scatter the chopped offal meat into shallow bowls. Ladle the stew on top, then garnish with the sautéed vegetables. Add any additional herbs or edible flowers on top. Drizzle with extra virgin olive oil and add freshly cracked black pepper to taste.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook