The Christmas Goblins of Greece Play Devious Tricks All the Way Till January

But don’t worry—polar plunges and putting children in ovens helps banish them.

On a cold and sunny morning on January 6 on the island of Kalymnos, Greece, a priest in full regalia stands on a dock of the harbor and throws a cross into the sea. A group of locals had been standing by, watching, but this is the moment everyone had been waiting for. Springing to life, a dozen young men dive into the chilly Mediterranean waters.

Swimming frantically, they all swirl and squint underwater, trying to catch the crucifix. Finally, one of them surfaces and raises the ornate, metal object high into the air. After handing it back to the priest, he’s wrapped in a towel, given flowers, and congratulated, for he is about to have a lucky year ahead of him.

He also just helped seal the deal in the final ritual to defeat and banish the kallikantzaroi, Greece’s infamous Christmas goblins.

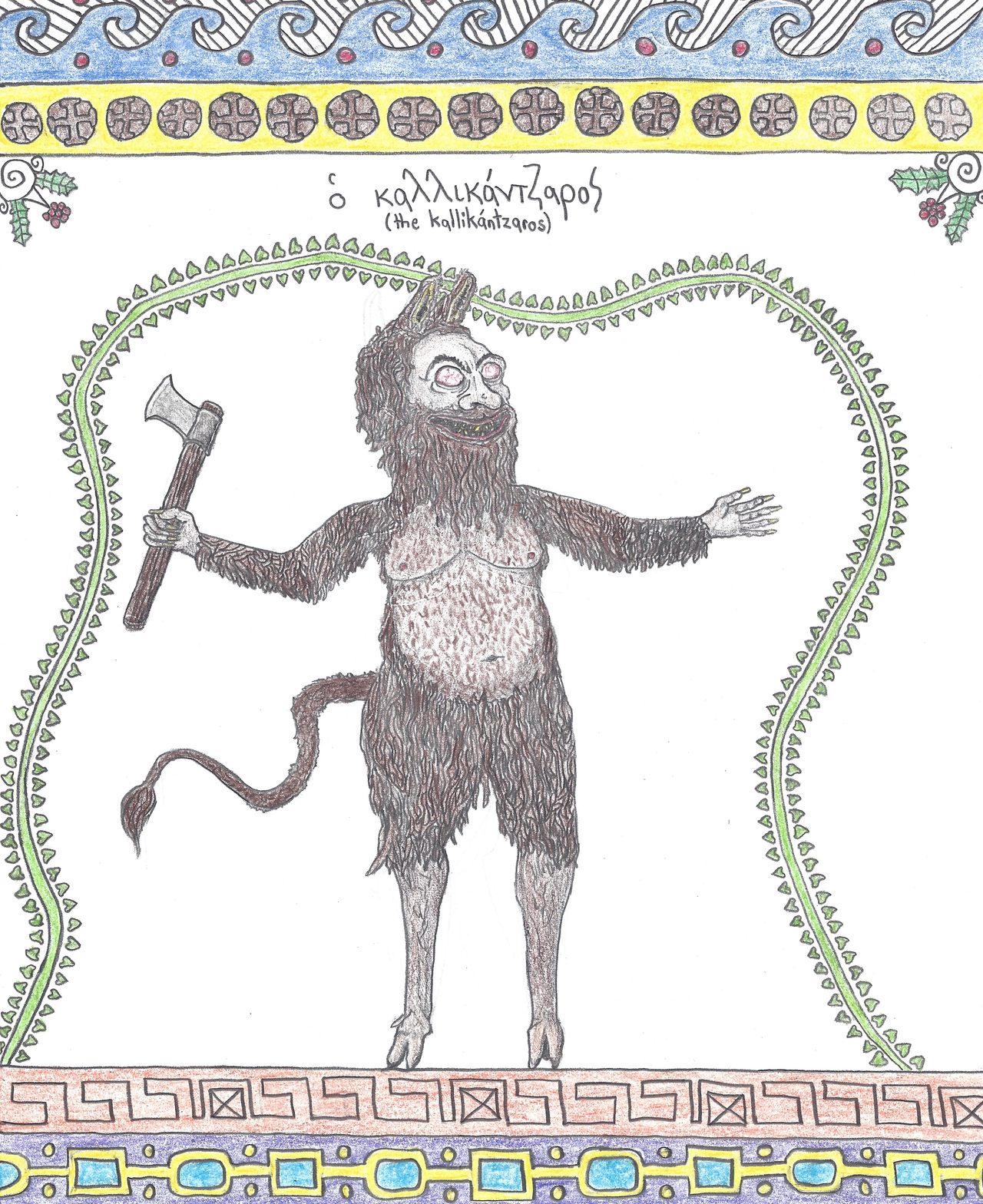

The kallikantzaroi are a major concern here in Kalymnos and throughout all of Greece. Looking like a mix between Gollum and an evil goat, these goblins are believed to emerge from the depths of the Earth during the Dodekaimero, the 12 days spanning Christmas to the Epiphany, wreaking havoc in the lives of humans. There are many remedies to keep them at bay, including burning a pair of old shoes, placing colanders on one’s doorstep, or hanging the lower half of a pig’s jaw over a home’s main door. But what ultimately drives these mischievous creatures back into the underworld is the Blessing of the Waters ceremony that occurs every year, and a kind of polar plunge that follows it.

As in many European countries, Greece’s Christmas traditions are both religious and folkloric. The kallikantzaroi belong to the latter category. They are mostly depicted as hairy creatures with animal features like hooves, claws, and tails. They come out at night, mostly down chimneys or through cracks in the walls, to play pranks on humans. These foul-smelling creatures are known to spoil milk, steal cookies, break furniture, and urinate on flowers. They are not very clever, speak with a lisp, and feast on snakes, worms, and frogs. If the kallikantzaroi invite people to dance, the humans risk losing their minds.

“The period of 12 days between Christmas and the Epiphany marks the period when Christ is born but not yet baptized, so it is considered a dangerous time,” says Evangelos Karamanes, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research Center in Athens. He adds that beliefs about evil forces being unleashed during this “unblessed window” are found across the Balkan region. “Basically the kallikantzaroi are an expression of this sort of dangerous cosmic turbulence.”

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact origins of these mythical creatures, but they’ve been around for hundreds of years. “The idea of kallikantzaroi gained ground especially during the Middle Ages,” says Tommaso Braccini, Professor of Classical Philology and Ancient Greek Folklore at the University of Siena.

The Middle Ages were marked by a decrease in communal life compared with antiquity, Braccini explains. There was less emphasis on public spaces and people spent more time at home. “Fears about beings that can roam around the home and break in were increasingly common at the time,” Braccini says.

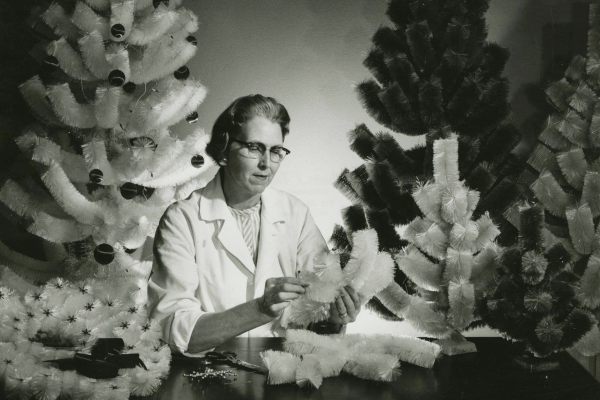

These fears lead to a series of preventing rituals, and people in rural areas and small islands still follow these traditions to prevent damage from kallikantzaroi. “Families may place pieces of meat or bread on their front porch or rooftops to distract them,” says Maria Eleni Perpiraki, who is from Athens and writes about the creatures and other Greek culture. Others may place cotton or threads in their gardens, as it is believed that the kallikantzaroi will be distracted by these items and start knitting instead of causing trouble.

Remedies also involve keeping a fire burning throughout the night (including one large log called Christoxylo, or “Christ’s wood”), covering surfaces with salt, placing cloves of garlic around the house, and painting cross symbols on exterior walls. Leaving colanders just outside one’s door is also believed to distract the creatures, since they would waste the entire night counting its holes; it’s believed the goblins can’t pronounce the number three, which is associated with God, so they start all over again with each attempt.

“In many parts of Greece, it was traditionally believed that children born around the same time as Jesus could become kallikantzaroi,” Braccini adds. Placing the baby’s feet near a candle light was believed to prevent claws from sprouting. Other strategies included putting the child in an unlit oven and asking them if they preferred bread or meat. “If a child picked bread, it was deemed safe, as bread had traditionally symbolized civilization,” Braccini says. “But if they said meat, it was a cause of concern, as it was believed to reveal the beastly nature of the child.”

Beliefs in these creatures evolved over time. With the spread of Christianity, Braccini explains, the myth of an evil creature breaking into the home was taken to symbolize the dangers of evil contaminating the Christian community. But in more recent years, the kallikantzaroi have become part of popular culture.

Well-known children’s songs feature the Christmas globins, and they are often part of Christmas school plays. They were featured in an episode of the famous TV show Grimm titled “The Grimm Who Stole Christmas,” while the Greek version of Harry Potter refers to the “Gringott goblins” as kallikantzaroi. Famed American writer H.P. Lovecraft was so impressed by the kallikantzaroi that he wrote several letters to fellow writers about this subject and based the “Outer Ones” creatures of his 1930 short story “The Whisperer in Darkness” on these goblins.

The kallikantzaroi are not officially recognized by the Greek Orthodox Church, but Braccini explains that priests tolerate beliefs in these types of creatures in a more informal way. The Blessing of the Waters ceremony symbolizes this “compromise” of beliefs, since “it is believed that what ultimately drives these creatures away is holy water,” as Karamanes says.

On January 6, priests go around towns, dip a cluster of sweet basil in holy water, and sprinkle it on each home. Priests also leave bowls of blessed liquid outside churches for people to collect and bring home for use against the goblins. “This is very effective against the kallikantzaroi, as they can’t stand holy water, and thus they return to the depths of the Earth,” Karamanes adds.

The largest ritual against the creatures happens during the Blessing of the Water ceremony. People all over Greece gather each year to watch local priests blessing the waters of rivers, lakes, or the ocean. The ritual even happens in Greek communities around the world. Last year in Port Melbourne, Australia, Steve Kykiris dove into Hobson Bay at Princes Pier. Helped by directions shouted from the crowd, he spotted the cross among the waves, and was the first to grab it, breaking up through the surface with the object in his fist. “It really was an amazing feeling,” he says.

While many of the anti-kallikantzaroi rituals are still practiced today, especially on islands and in rural areas, the image of the creature has evolved in recent times, Karamanes says. “Traditionally kallikantzaroi were depicted as quite nasty,” he says, “while today they are more seen as goofy goblins.”

But even if they lost some of their “teeth,” the kallikantzaroi still play a key role in people’s imagination, especially for children. Kamandes says they ultimately represent the type of chaos that many of us can feel during the holidays. He explains that people often jokingly refer to the kallikantzaroi to explain plans gone awry. It’s a nice option to have during the inevitable chaos of the season. Whether or not you want to jump into a cold sea to rid whatever problems or mischief is occuring, next time your holiday plans fail, you can at least blame it on the kallikantzaroi.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook