Argentina’s Ex-President Appears to Be Cursed

By his own acknowledgment, Carlos Menem brings bad luck.

Among the superstitious citizens of Argentina, one name keeps voices hushed: ex-president Carlos Menem, who ran the country from 1989 to 1999. Saying his name out loud—or worse, coming into physical contact with the man—can bring down sports teams, put people in the hospital, or even bring death. According to local legend, this real-life Voldemort, he-who-must-not-be-named Menem has a clear track record of suffering seriously bad luck, and many believe he brings those around him into his apparent curse.

As so many legends go, it’s tricky to pin down exactly when these beliefs began. Not only is Menem ill-remembered by many for the perception that he brought on Argentina’s 2001 economic crisis, he’s also associated with leaving actual death in his wake. According to The Argentina Independent, shortly after Menem won the presidency in 1989, he appointed two new politicians to office; mere days after accepting the job the Minister of Economics died of a heart attack-car accident combination; months later the Minister of Health followed due to an aerial accident.

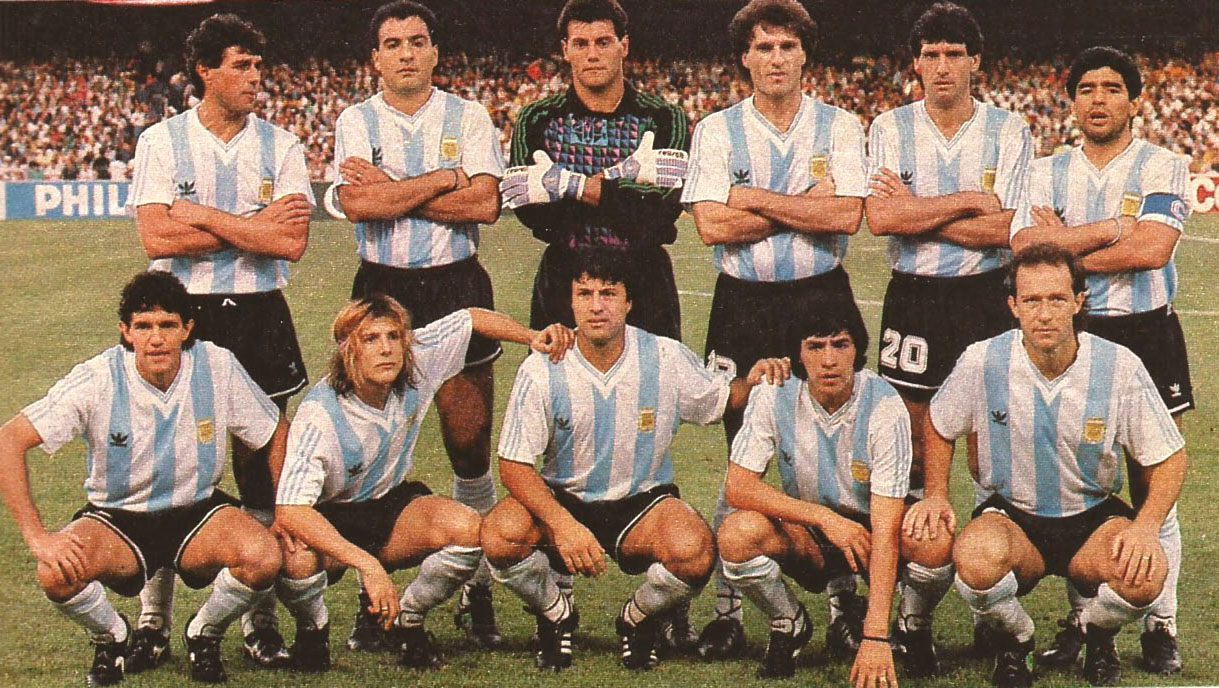

But it wasn’t until the 1990 World Cup that matters began to look more actually cursed. Menem attended the game in Milan, and attempted (yet failed) to shake the hand of goalie Nery Pumpido; instead, Menem patted his knee, the Argentina Independent reported. Soon after, Pumpido broke his kneecap, debilitating him for the rest of the game, and Time Magazine conceded many labeled him a “jinx,” the Argentinian for which is “mufa.”

“This is the darkest day of my career,” Argentina’s team coach told United Press International. It should be noted that at the 1990 World Cup, according to the New York Times coverage of the game, Menem did more than pat the knee of more Pumpido; he also suggested a lineup change along with other game changes that caused significant distraction.

No matter the cause, the initial damage was done. Thereafter, Menem seemingly flitted from one personal delight to the next, leaving destruction in his wake. An avid sports fan, Menem played with local teams or attended games, after which the players would inevitably fail in the game or their career. This is assumed of tennis player Gabriela Sabatini, whose career supposedly plummeted after a match with he-who-must-not-be-played—though some teams seemed to interact with the then-president without disaster.

In 1991, The Independent reported that “Argentines fear their leader’s jinx” after Menem met Ferrari’s German driver Michael Schumacher and shook his hand, which some believe caused a near-loss. Following this, Menem was banned from watching his favorite soccer team play. After all, when he “shook the hand of Argentina’s world powerboat racing champion Daniel Scioli in 1989, Mr Scioli’s boat crashed and he lost an arm,” The Independent reminded its readers.

The list goes on in terms of danger when it comes to Menem; he was linked superficially to the 1989 San Andreas Fault earthquake. Even non-sporting celebrities are not safe, according to the lore. Menem’s love of tango brought him to the bedside of sick-but-recovering tango singer Hugo del Carril in 1989, and apparently after a visit from the then-Argentine president, he suddenly passed away; Astor Piazzolla fell to the same fate after a visit in the hospital from Menem, just a few years later.

Many a heart must have frozen, then, at the possibility that Menem might have run for a third consecutive presidential term in 1998, which would have required a court appeal process and constitutional amendment. (Argentina allows three presidential terms, but not when served consecutively.) Menem claimed not to want a constitutional change, and didn’t attempt one. A few years later, he entered the 2003 presidential election against another member of his own party, then withdrew—a move that some said was meant to cause trouble.

“Over his wildly fluctuating career, including a decade as president and many a scandal and probe, Carlos Menem has done his country some services and many disservices,” The Economist wrote at the time, referencing in part the many scandals surrounding money that Menem spent from public resources.

Argentinian politics are steeped in weird luck and possible curses, including one historic curse that supposedly prevents any governor of Buenos Aires from becoming president, despite being from a populous epicenter. Jill Hedges wrote in Argentina: A Modern History, that “it is popularly supposed that there is a sort of curse on the governorship of Buenos Aires, as no politician holding that important office has ever been successful candidate for the presidency thereafter.” She added that however enticing it may be to think that bad luck follows Argentinian leaders in general, the trouble might actually “reflect the virtual impossibility of governing so vast, diverse and problematic a province effectively.”

Menem’s supposed bad luck affects his own life too; he garnered public scandal for his unhappy marriage, and in a sad turn for Menem in 1995, his son passed away in an accident while flying a helicopter. Menem himself is convinced that a curse weighs on him, according to a December 2007 update on his life in Minuto Uno; the article claimed that “Dead relatives, sick people, depressions and forgetfulness are part of the misfortunes that Menem attributes to some spell against him.”

Occasionally Menem’s past comes back to bite him, either by insinuating another politician committed murder or in the form of a plain old court appearance. In 2013, Menem was sentenced to home arrest for smuggling weapons in the ‘90s, and in 2015 faced embezzlement charges from accepting bonus payments during his time in office; while these seem the result of bad choices rather than bad luck, Menem claimed he didn’t know that accepting the payments was ever illegal.

Argentines who believe in the curse often substitute “Mendez” or “Mendem”, or really anything similar enough to stand in for the former Argentine president’s actual last name. It’s up to you to believe what you will, of course—but if you’ve been reading this article aloud, it may be too late.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook