Japanese Scientists Turn Literary Detectives to Study a 1770 Magnetic Storm

They think it might have been the largest ever seen.

In mid-September 1770, the sky over the ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto turned crimson. Hundreds of thousands of people would have been looking up at an enormous aurora that stained huge swaths of the night sky. New research, published in the journal Space Weather, combines ancient accounts of the phenomenon with astrometric calculations to suggest that this heavenly light show may have been caused by the largest magnetic storm ever observed.

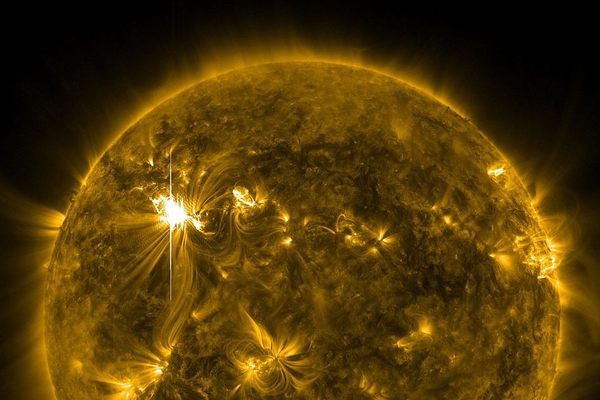

A similar storm in 1859 caused significant disruption to communication networks across Europe and America. This Japanese storm, however, may have been as much as 7 percent larger. It’s unusual to see auroras outside of the polar regions, except in the case of particularly severe magnetic storms caused by solar flares. Written records of these out-of-place auroras are usually the best guide scientists have to where and when big space storms occurred in the past.

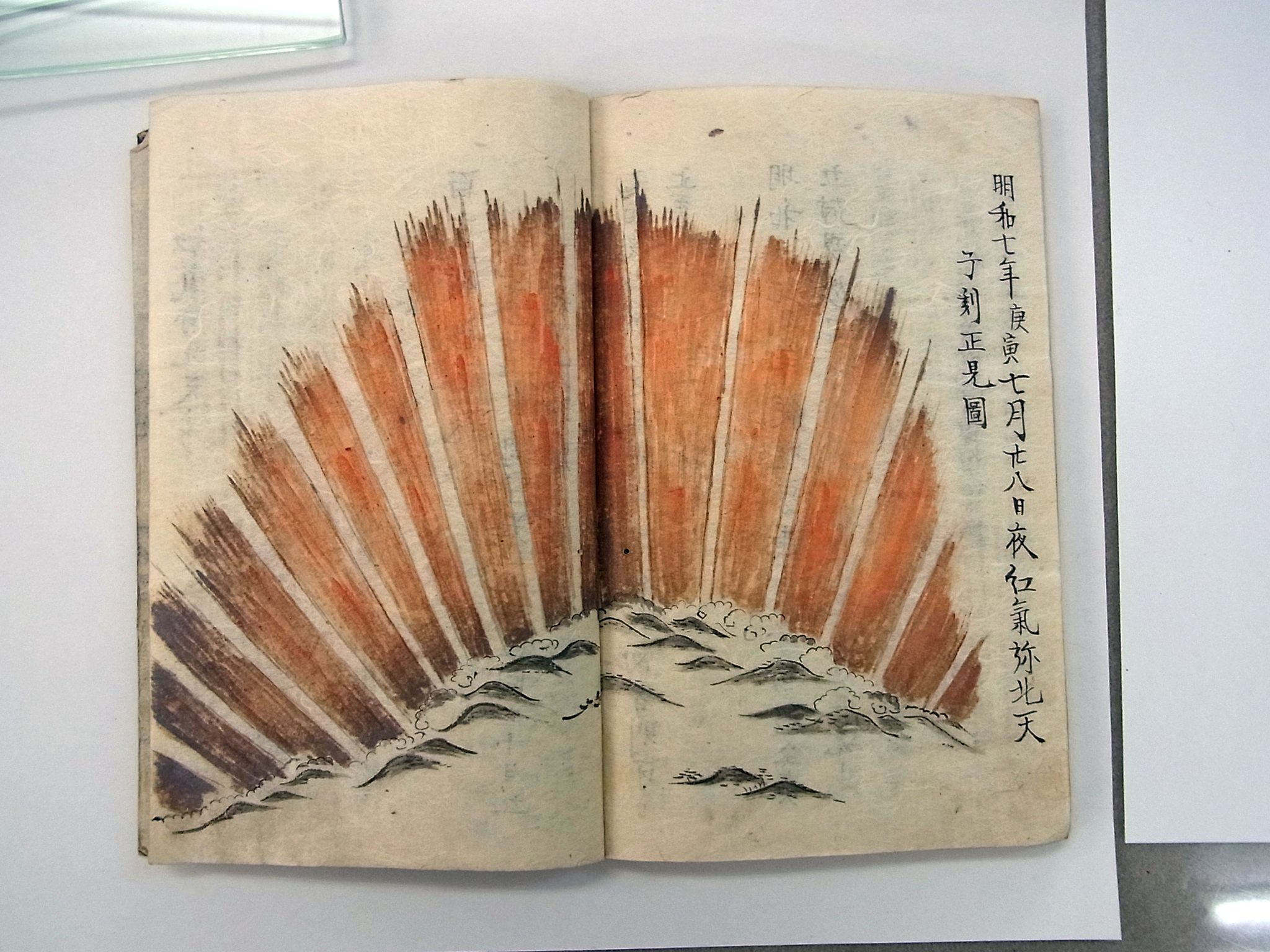

To study this one, researchers from the National Institute of Polar Research worked with the National Institute of Japanese Literature. They drew information from a detailed painting in the manuscript Seikai, or Understanding Comets, and a recently discovered diary from the prominent Higashi-Hakura family. The diary describes how, late that night, “red clouds covered half of the sky to the north, toward the Milky Way,” and “a number of white vapors rose straight through the red vapor.” Based on the painting and description, and the location of the Milky Way in the sky at the time, scientists were able to determine the geometry of the aurora and, in turn, estimate the strength of the storm that caused it. “The enthusiasm and dedication of amateur astronomers in the past provides us an exciting opportunity,” researcher Kiyomi Iwahashi said in a statement.

Massive magnetic storms present serious risks to communications and power grids, and it’s hoped this kind of work will help us understand them a little better. But it’s hard to tell just how at risk we are. “We are currently within a period of decreasing solar activity, said researcher Ryuho Kataoka, “which may spell the end for severe magnetic storms in the near future.” Only last month, however, an “extremely fast coronal mass ejection,” which could have been powerful enough to cause problems, just missed the Earth. Phew.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook