Found: The First Anglo-Saxon Building in Bath

The discovery, in a city famed for its Roman ruins, may mark the site of England’s first coronation.

Characterized by its overcast skies and frequent precipitation (as memorialized in many a Gothic novel), Britain’s gloom is warmed by at least one balmy gem: the perpetually heated geothermal springs of Bath. Founded as a spa by the Romans, Bath’s elegance was revived centuries later by King George I, II, and III of England, who injected the city with a healthy dose of Palladian and, yes, Georgian architecture.

But long before Bath became a project of those Hanoverian royals, it was the site of England’s first coronation—of King Edgar the Peaceful, in 943. Until now, however, no one knew exactly where that ceremony took place. The specific site of the crowning was lost in the steady tick of Bath construction and resettlement.

Now, archaeologists have uncovered the first Anglo-Saxon structural remains in Bath, in the shadow of the city’s famous abbey. And they may have been where England’s enthroning tradition began.

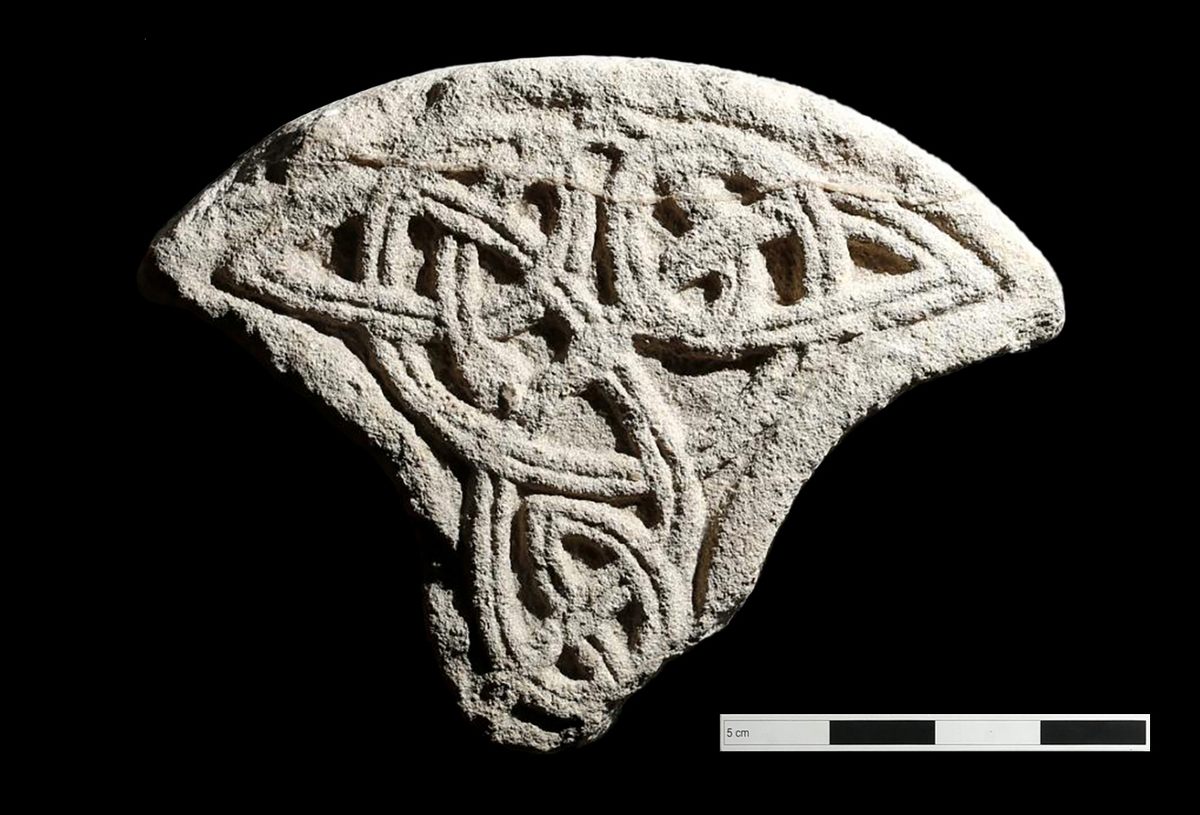

By using charcoal found at the site, the excavation team was able to radiocarbon date the remains to sometime between the years 600 and 1000—the thick of the Middle Ages. The structure of the remains, which form distinct apsidal (semi-circular) shapes, clearly suggests a religious building.

“We know that the structures we uncovered are within the monastic precinct and immediately south of an extensive Saxon cemetery, which was also excavated as part of the project,” says Cai Maison, a senior project officer at Wessex Archaeology. “Now [that] we have the radiocarbon dates, we can be confident that these are monastic buildings in the broad sense.”

In the 18th and 19th centuries, archaeologists working in Bath were pretty focused on finding and cataloguing Roman remains. That meant that much of what they found in the layers above those remains—namely, Norman and Saxon relics—was paid little mind. That began to change only somewhat recently.

“Late 20th-century archaeologists were far more careful,” says Bruce Eaton, a project manager at Wessex Archaeology. “But by [that time], most of the post-Roman archaeology within the Baths complex had been removed.”

The recent discovery was part of the city’s $25 million Footprint project, an initiative to restore the Bath Abbey’s collapsing floor, among other goals. But digging around the abbey’s foundation has also turned up that which was long ago trampled—including what seems to have been a coronation site over 1,000 years ago.

In Edgar the Peaceful’s time, Bath sat between two kingdoms: Mercia and Wessex. King Offa of Mercia had significantly renovated Bath’s religious buildings a century prior, making the city a uniquely poised outpost. Following Offa’s work, King Alfred the Great primped up the town a bit more, annexing it for Wessex.

“Bath has a strong connection with both these preeminent kingdoms, which Edgar want[ed] to unite into one English state,” Maison says.

While England had of course had kings before, none had had a coronation ceremony to mark his tenure. (In Edgar’s case, coronation did not occur at the time of ascension, but toward the culmination of his reign.) All coronations of English monarchs since have been based on that initial event in Bath, whose exact location was obfuscated by sparse record-keeping and poor archaeological practices. The current work seeks to avoid previous missteps, and to take a more holistic approach to peering at the past.

“The archaeological work associated with the Footprint Project has highlighted how, far from being a ruined shell, Bath continued to function as an important settlement throughout the Saxon and medieval periods,” Eaton says. “[It] has highlighted how there is so much more to the city’s history than its famous Roman remains and Georgian buildings.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook