A Glimpse of American History Through the Process of Becoming a Citizen

Personal stories of naturalization from the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

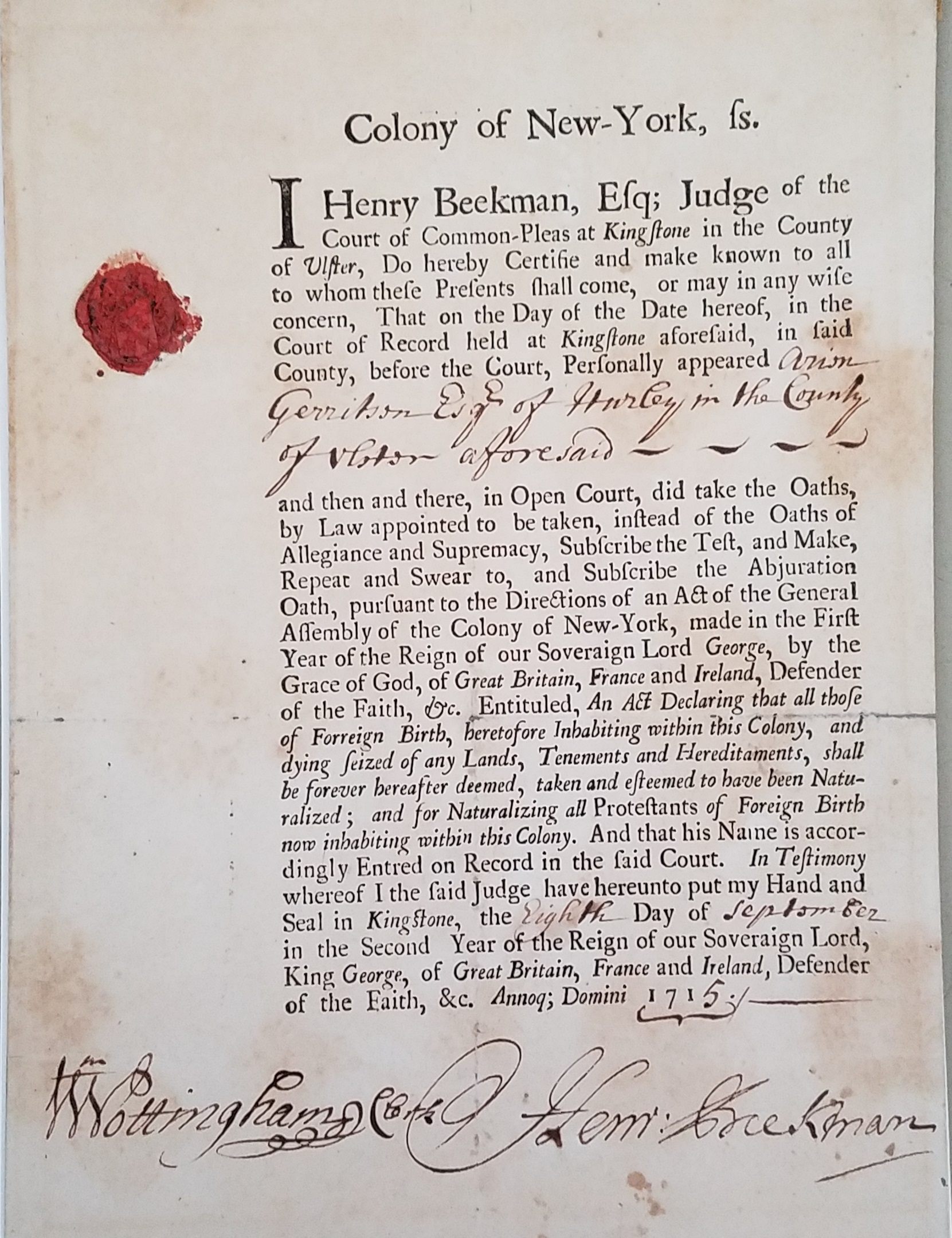

The year was 1715 and Arien Gerritsen, a Dutch Protestant man living in the colony of New York, had some paperwork to fill out. That year, freshly coronated King George I had mandated that eligible foreign-born Protestants in the colonies renounce their foreign citizenships. So in September, Gerritsen appeared before a judge in Ulster County, abjured Dutch citizenship, pledged an oath of loyalty to the absent monarch, and filled out a form letter sealed with a dribble of red wax. The document was packed with dense thickets of jargon, punctuated by spaces for scribbling in personal details—“kind of like a lease today,” says Nina Nazionale, Director of Library Operations and Curator of Printed Collections at the New-York Historical Society Library. Make your mark, and join the empire.

Procedures that allowed a person to be naturalized as a citizen have evolved, along with who is eligible, throughout the country’s history. Nazionale recently curated an exhibition at the Historical Society Library to trace certain segments of this meandering path and along the way she paused to wrestle with the symbolic heft of citizenship as an idea. What does it mean to acquire this designation, and what does the process reveal about the era and the country that confers it?

The exhibition compiles items from the library’s collection related to naturalization, including legal documents, mass-produced pamphlets, and other materials dating from 1715 to the 1950s. The artifacts don’t illustrate all of the tangled permutations of the laws, nor how unevenly enforced they could be. (Before the Constitution was drafted, naturalization was often granted preferentially to Protestants, for example, though religious requirements tightened and slackened over the years.) Many of the documents anchor this knotted history in personal stories. These objects, salvaged from obscurity, have given researchers a way to track the everyday lives that unfolded in the shifting shadow of politics and policy.

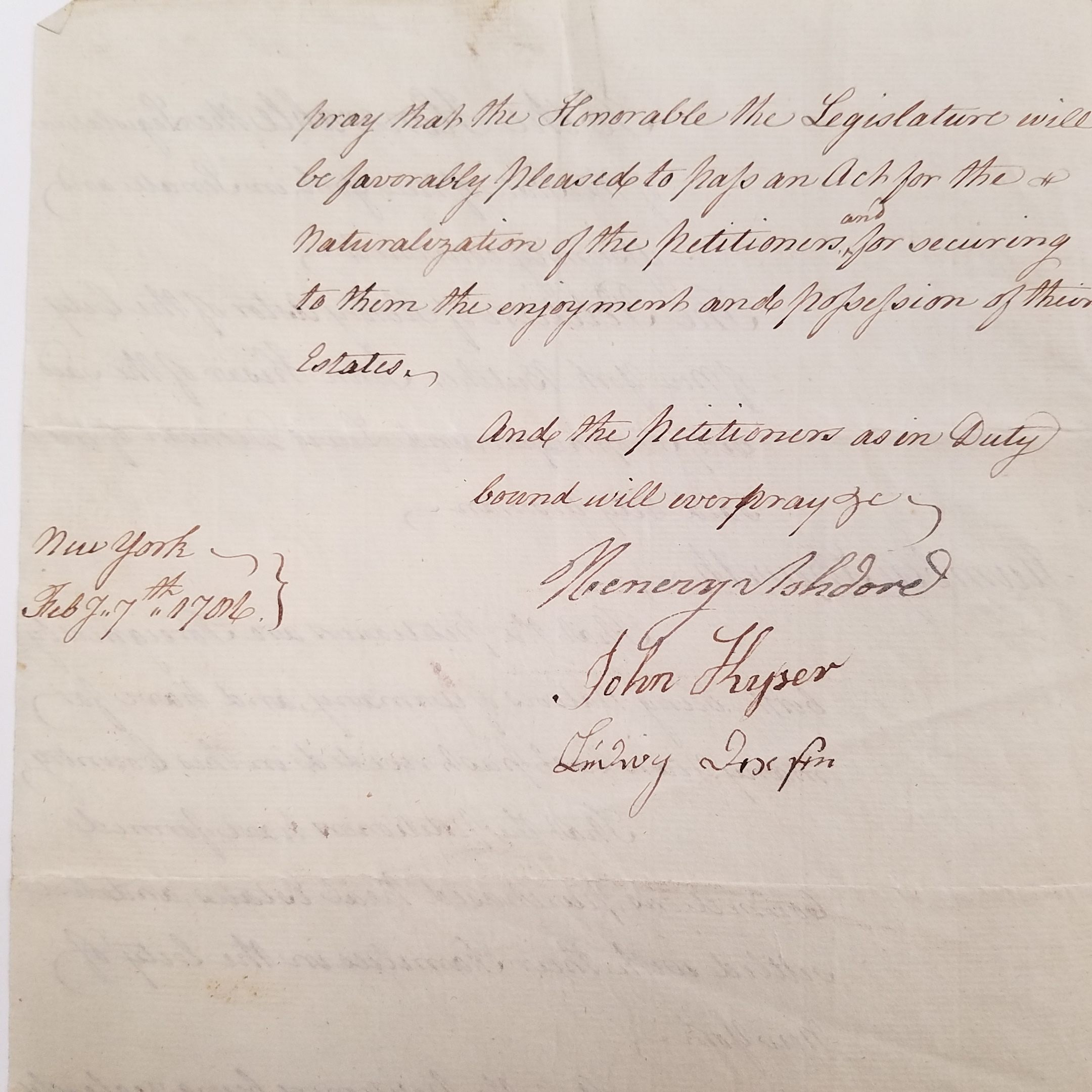

Before the Revolutionary War, Nazionale says, some residents could choose to have their citizenship tied to particular colonies, or (for a hefty fee) even appear before Parliament to become a true British citizen. Then, as the new country took shape, aspiring citizens had to make their cases to the fledgling U.S. government. In 1786, Henry Astor, the older brother of future tycoon John Jacob Astor, was a butcher recently landed from the German state of Baden-Württemberg. He outlined his case for citizenship in a petition to the New York legislature. The argument went like this: He’d been living in the country for three years, purchased real estate, and sprouted roots in the community. He swore himself to be “zealously attached to the freedom and independence of America.”

Nazionale can’t be sure how the judge decided in Astor’s case, but, she says, citizenship would have been viewed as “a symbol of moving up in the world and in the country.” Four years later, the Naturalization Act of 1790 extended eligibility to free white people “of good moral character” who had lived in the United States for at least two years. In an article for Prologue, the magazine of the National Archives, the historian Marian L. Smith pointed out that this law didn’t explicitly bar white women from becoming naturalized citizens. If they were married, their status was often folded into their husband’s.

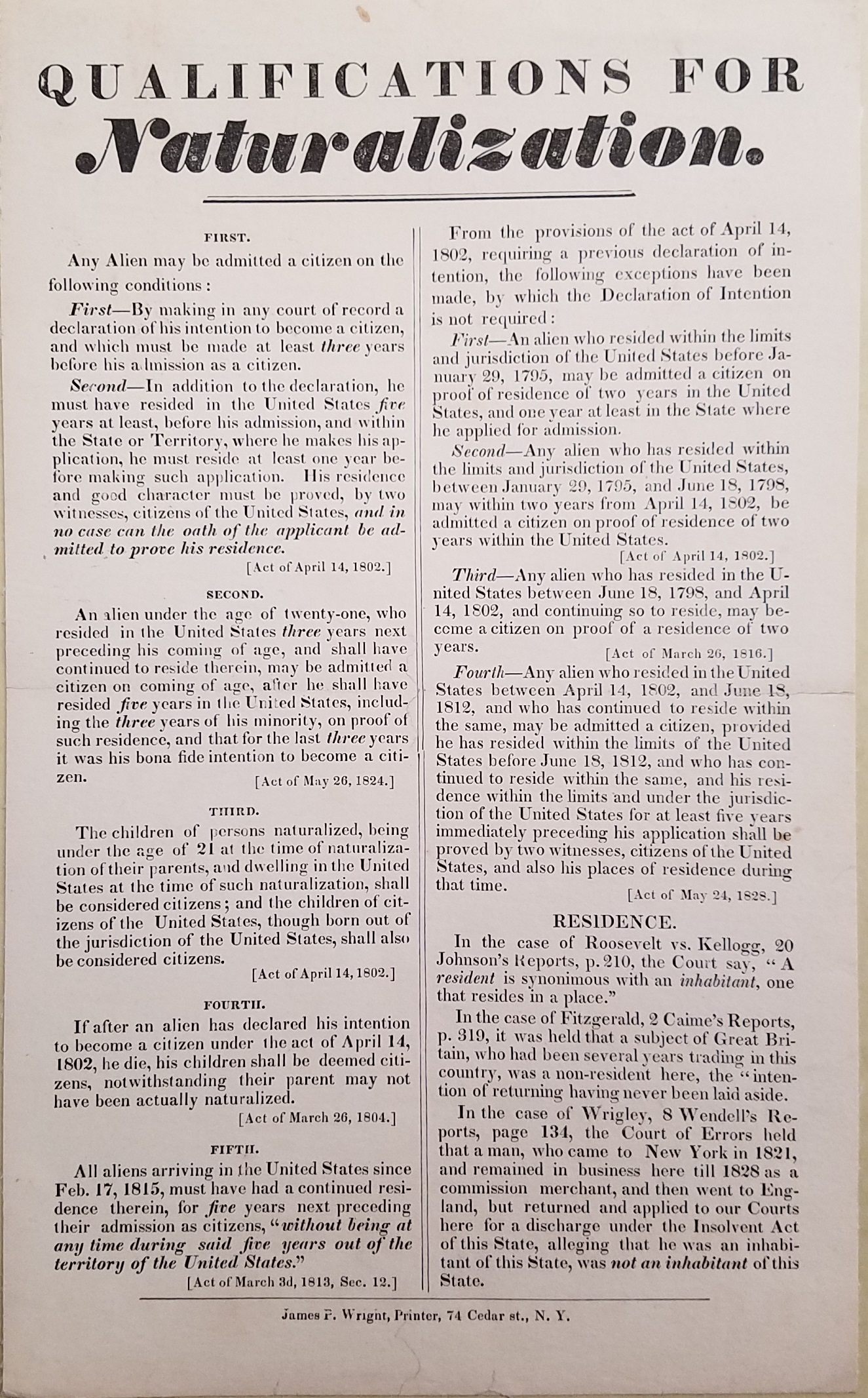

The 1790 law didn’t mean that rules and procedures had crystallized, though. They continued to change, dramatically and often. Anti-immigrant sentiment swelled over the ensuing few years, culminating with the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Signed by President John Adams, these bills bumped the residency requirement to 14 years. In 1802, the requirement fell back to five years. A dense handbill published by a New York printer in 1828 recounts a smattering of six changes recently tacked on or tinkered with.

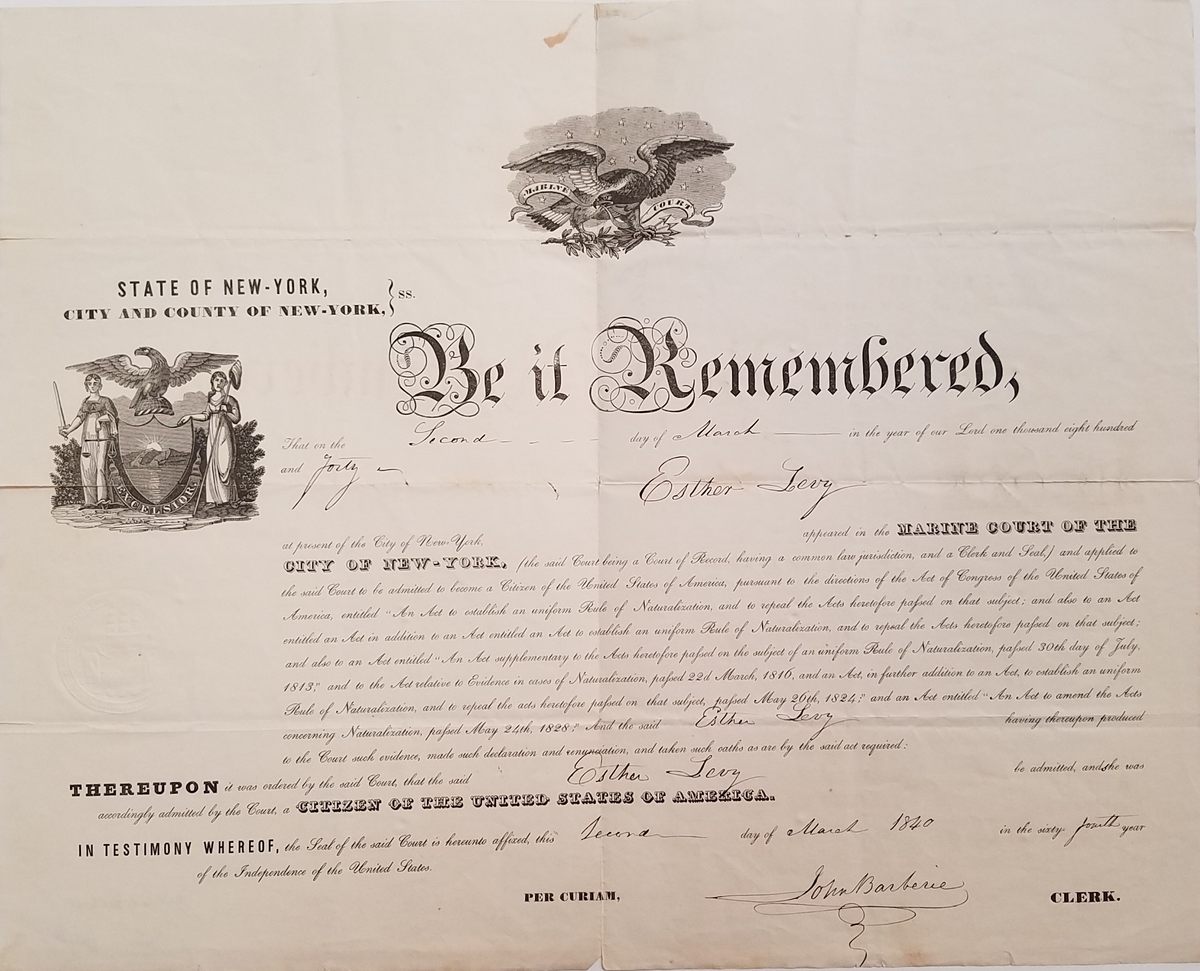

The certificate commemorating the naturalization of a woman named Esther Levy, in March 1840, testifies to more of that ongoing editing. Sandwiched between the swirling calligraphy and official insignias is a dense block of text summarizing more rules that had been enacted and repealed. For example, the document’s fine print is a cluttered with references to “an act in further addition to an act to establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization,” and alludes to supplemental tweaks in 1813, 1816, 1824, and 1828.

Through all these changes, citizenship was still largely denied to anyone without a European background. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment broadened eligibility, and two years later, the Naturalization Act of 1870 explicitly noted that “aliens of African nativity” and “persons of African descent” could become citizens. In 1882, though, the Chinese Exclusion Act cracked down on immigration from China, and wasn’t lifted until 1943. All Native Americans were granted citizenship in 1924. A pathway for immigrants from India and the Philippines to become naturalized citizens emerged in 1946, when President Harry Truman signed the Luce-Celler Act. The exhibition doesn’t grapple directly with racism, sexism, or xenophobia, but the specter of all three casts a shadow over the perpetually changing laws.

Exams became part of the naturalization process in the 19th century, based on the notion that citizenship was a right to be earned, in part through a working knowledge of civics and the Constitution. For decades, though, these exams were haphazard—often a battery of impromptu questions lobbed out in court and answered on the spot. Even after naturalization proceedings were standardized under the umbrella of the Federal Naturalization Service in 1906, “courts continued to administer the tests as they had before—orally, extemporaneously, and with little uniformity across jurisdictions,” according to the Department of Homeland Security.

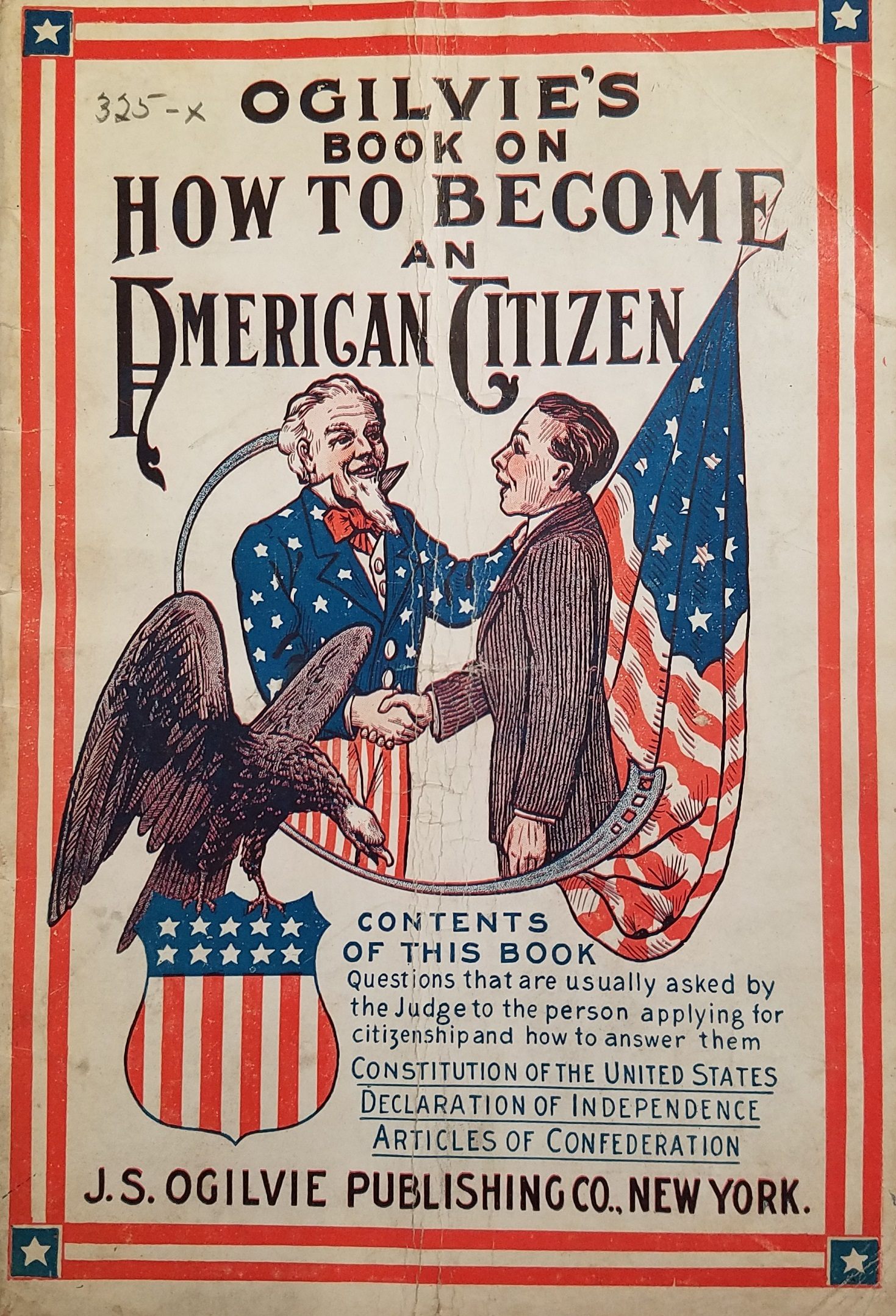

Still, local governments and private publishers produced study guides that helped applicants cram for whatever questions the test might bring. Uncle Sam clasps an applicant’s hand on the throughly spangled cover of one such book in Nazionale’s exhibit, published by the J.S. Ogilvie company in 1929. The guide was a departure for the commercial publisher, whose trade was largely in pulpy whodunits and other dime-store novels. But Nazionale imagines such pamphlets were flying off newsstands and drugstore shelves in the late twenties, when immigration numbers were steadily climbing. The year the book was published, 224,728 new citizens were naturalized—the second-highest number since 1907.

To help contemporary applicants brush up for the current version of the test, which today includes 100 questions about branches of government, citizens’ duties, and geography, the Historical Society has also teamed up with the City University of New York to use items in its collection as teaching tools. In classes about navigating the exam, participants might learn about voting rights through studying a yellowing pennant emblazoned with the slogan “Votes for Women.” For context on the Declaration of Independence, they might scrutinize Johannes A.S. Oertel’s painting of torch-wielding New Yorkers and Continental soldiers lassoing and toppling a gilded statute of King George III in a gleeful melee.

Some of the ephemera in Nazionale’s show drifted in with family papers, while other items were plucked from the institution’s collection of 20,000 broadsides, and still more were donated. Nazionale sees that impulse continuing today, as people approach the library with things—including items related to citizenship—they’ve held onto. “People are thinking, ‘I know this seems kind of not a big deal,’ but someone has an idea about the importance of history, and keeps it,” she says.

Nazionale says she’s determined to usher this collection into the fractious 21st century, including with materials that are missing, such as ones that describe the experiences of marginalized groups. Brand-new acquisitions bring the story right up to the present day. One former staff member recently passed the naturalization exam, and then donated his homemade flashcards. A future version of the exhibition could include his test-prep materials, tucked carefully inside a glass vitrine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook