100 Years Ago, American Women Competed in Intense Venus de Milo Lookalike Contests

Venus as painted by Henri-Pierre Picou. (Image: Wikipedia)

In February 1916, two prestigious northeast American liberal arts colleges engaged in a spirited war of words, goaded by the media. The conflict, between Wellesley in Massachusetts and Swarthmore in Pennsylvania, did not pertain to academics, admissions, suffrage or sporting teams. They were fighting over which college’s female students most closely resembled the Venus de Milo.

At the time, American women were still getting used to breathing easily, having wrestled free from the tightly laced corsets and bulky bustles of the Victorian silhouette. But in the absence of these strictures they faced a new kind of aesthetically minded pressure: the need to make their measurements correspond to those of a Greco-Roman goddess. The soft curves of Venus—Aphrodite to the Ancient Greeks—were being exalted once again as the paragon of female beauty.

Accordingly, the nation embarked on a quest to find a living, breathing woman whose body was of exact Venusian proportions.

Venus de Medici. (Photo: Yair Haklai/Wikipedia)

The Wellesley-Swarthmore tiff began on February 10, 1916, when Wellesley released the composite data of its students’ measurements. They seemed close enough to Venus’ proportions to invite goddess comparisons—the average young woman at Wellesley apparently had a waist circumference within half-an-inch of the hallowed Venus de Milo trunk circumference.

But on February 15, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Wellesley’s “composite Venus” was “outdone by Miss Margaret Willett, the beauty of Swarthmore college and leader in women’s athletics, according to measurements of Miss Willett made public today by her friends.” Willett’s supporters insisted that her figure trumped the collective beauty of Wellesley women since her measurements varied from those of the Venus de Milo by mere fractions of an inch. Her bust, in particular, was “practically the same.”

A woman being measured by a thoracimeter at the physical training department of Wellesley College in 1915. (Photo: Bain News Service/Library of Congress)

In America, the detailed measuring of college students had been standard practice since the 1890s, when the physical culture craze took off at universities. Over the next few decades, physical educators, particularly Dr. Dudley Allen Sargent, director of the Hemenway Gymnasium at Harvard University, collected measurement cards from students all over the northeast. Participating institutions included prestigious women’s liberal arts colleges such as Smith, Bryn Mawr, and Mount Holyoke, in addition to Wellesley and the co-educational Swarthmore and Oberlin.

These measurement cards did not require just height, weight, bust, waist, and hips. There were 60 required measurements per person, including instep, wrist, forearm, armspan, and “ninth rib.” And all this data was being put toward new and novel applications. In 1893, Sargent used composite figures from female students’ measurements to sculpt a statue and exhibit it at that year’s Chicago World’s Fair. This figure came to be known as the “Harvard Venus.” Visitors to the fair were invited to examine it, reflect on how their own bodies compared, and submit themselves to be measured for Sargent’s data collection project.

Professor Sargent: physical educator; lady measurer; data hound. (Photo: Bain News Service/Library of Congress)

As the 20th century kicked into gear and the physical culture craze continued at institutes of higher learning, the idea of using measurements to search for a Modern American Venus became more overt. In 1910, Sargent was quoted extensively in a New York Times article entitled “Modern Woman Getting Nearer the Perfect Figure.”

In it, Sargent derided the “overwomanized” silhouette of the Victorian era. “The American woman of to-day is becoming more like the Greek ideal of the beautiful,” he declared. “True beauty consists of symmetrical and proportionate development of parts with adipose [fat] enough to cover the angles and hollows.”

Venus of Arles at the Louvre. (Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikipedia)

By this time, Sargent had collected the measurements of over 10,000 female students, yet he claimed he had still not encountered the ideal woman. “Among the many thousands who have been measured at the gymnasium, not one has fulfilled every requirement,” he told the Times. The closest was Annette Kellerman, an Australian swimmer and vaudeville star who stood five-foot-four-and-a-half and sported a 35.2-inch bust, 26.2-inch waist, and 37.8-inch hips. Sargent called her the “perfect woman” for publicity purposes, but he was rounding up.

Over the next decade and a half, Sargent and other physical culture enthusiasts continued to scour the nation to find their human Venus. New contenders were discovered frequently. A Washington Post headline in 1912 proclaimed ”Cornell Has Perfect Woman,” and named basketballer Miss Elsie Scheel of Brooklyn as its Venus de Milo equivalent.

In 1913, the Oakland Tribune declared ”New Venus is Found By Harvard Savant”—the savant in question being Sargent and the Venus being 19-year-old swimmer Madeline Berle of Revere, Massachusetts. In 1916, New Yorker Irene Kelynack, 21, was dubbed a “flesh-and-blood replica” of the ancient statue, while in 1919 the Tribune blared “Los Angeles Has Perfect Girl of Venus Physique,” and identified athlete Rosalind Smith as the new paragon of female perfection.

The ridiculous thing about all this—well, one of the ridiculous things—is that these women’s measurements varied from one another by several inches. Not only that, but they were being compared to different standards, for there were multiple versions of the Venus de Milo’s measurements. Some physical culture practitioners quoted the statue’s bust-waist-hip stats as 39-26-38, while others believed she measured in at 34.75-28.5-36. The only stat everyone could agree on was the Venus de Milo’s height, which was set at five-foot-four.

By 1919, the physical perfection of Venus was being questioned. “I do not consider the Venus de Milo perfect,” huffed anthropometrics specialist L.E. Eubanks in Social Progress. “Any woman with a 26-inch waist and a 39-inch bust should have an ankle larger than 7.4 inches.”

The Venus de Milo: a total uggo, according to L.E. Eubanks. (Photo: Tom King/Wikipedia)

Still, the Modern Venus searches continued. In October 1922, a particularly contentious competition took place at the Physical Culture Show and Beauty Contest held at Madison Square Garden. At this event, according to the Pittsburgh Press, five male judges, all sculptors, “led the young women contestants into a private room in the Garden and minutely inspected the competitors one by one.”

The women were naked during these inspections, “wearing not even so much as a pair of slippers on their feet.” One of the contestants, Ann Hyatt, told the Press that she was instructed to remove her bathrobe and then bathing suit. When she murmured that the situation was “very embarrassing,” Herman Moens, the head judge, remarked, “But the body is far more beautiful nude.” Then, according to Hyatt, “[t]he other four repeated in a kind of chorus, ‘Yes, indeed. By all means. It certainly is.’”

After every contestant had been subjected to a thorough visual inspection, 18-year-old Dorothy Knapp (five-foot-three; 35.5-25-35) was declared the winner. This devastated Hyatt (five-foot-four; 34.75-28.5-36.5), who had been determined to claim the Miss American Venus title. Refusing to accept the judges’ decision, Hyatt sought the services of a lawyer, who announced his client’s plan to take the case to the Supreme Court of the State of New York. “Miss Hyatt is really, in fact, the most perfectly formed woman in America, the modern Venus of the United States,” her lawyer, David Steinhardt, said. “[I]t is a matter of serious importance to herself, to her husband, and to her children that she should not be defrauded of this conspicuous distinction.”

Dorothy Knapp, the winner—wrongfully, according to some—of the 1922 Miss American Venus contest. (Photo: Bain News Service/Library of Congress)

Miss Hyatt did not have a husband or children. She was just thinking ahead. Her lawyer even laid out a plan for how the Supreme Court could verify Miss Hyatt’s rightful claim to the Modern Venus title over Miss Knapp: “we are prepared to set up in the court room a life-size statue of the great Venus de Milo, and produce our client in court to establish by a series of minutest measurements that Miss Hyatt’s figure more closely follows the dimensions of that accepted masterpiece of art.” (For the arms, famously missing from the statue, Hyatt and her legal team planned to consult the “well-known restoration as made by the distinguished artist, Henri Rochefort.”)

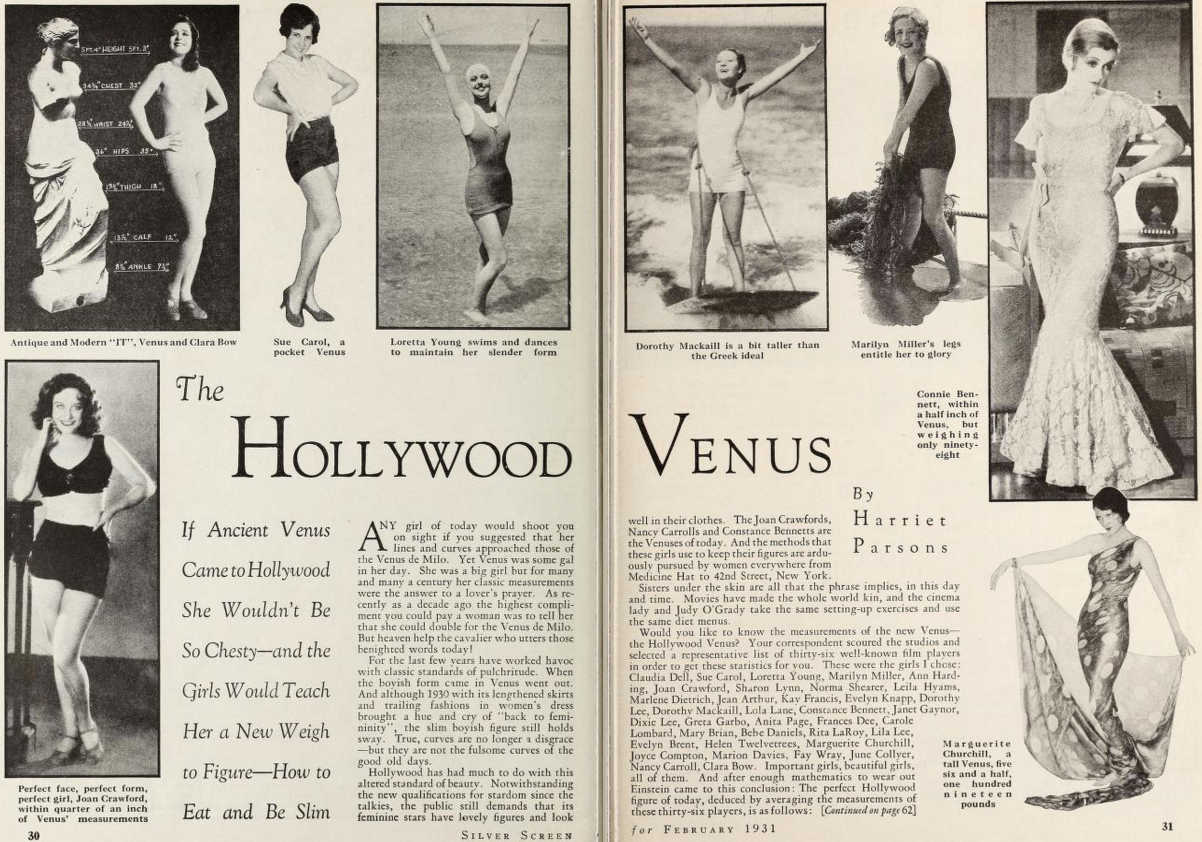

Sadly for Miss Hyatt, her case was judged to be without merit. But times were changing anyhow—the flapper fashions newly in vogue looked best on tall, slender figures, and the Venus de Milo was starting to look a little too plump. In April 1923, the New York Times introduced the world to the “new Venus, whose proportions have been reduced by the athletic tendencies of the modern girl.” To be a true American Modern Venus, women now “must be 5 feet 7 inches in height, a perfect 34, with 22-inch waist and 34-inch hips.” Furthermore, “[t]he ankle should measure 8 inches and the weight not exceed 110 pounds.”

By 1931, magazines were touting a slimmer Venus whose measurements were much altered from those of the Venus de Milo. (Image: Silver Screen/archive.org)

And just like that, the beauty rules changed again. After decades of searching and dozens of contenders, America hadn’t found its perfect living, breathing reincarnation of Venus—because she didn’t, and couldn’t, exist.

Three months after the “new Venus” proportions were announced, Dr. R. Tait McKenzie, sculptor and former director of physical education of McGill University, told a crowd of female college students that he had given up on looking for ideal figures among America’s young women. Having studied hundreds of measurement cards from colleges in the country’s east, he declared that the women were all ”slab-chested and knock-kneed”—the “antitheses of Venus,” according to the Oakland Tribune.

But the fruitless quest for Venus was not the fault of the many thousands of women whose measurements were scrutinized and deemed imperfect over the years. The mistake was in equating human beings with lifeless, albeit carefully sculpted marble. Even L.E. Eubanks, the statue-scrutinizing anthropometrics guy who once declared the Venus de Milo “a trifle top-heavy,” acknowledged the folly of trying to compare live women to ancient sculpture.

“Be a statue perfection itself, it still leaves too much to the imagination,” he wrote in 1919. “[T]here are too many important elements of physical excellence expressible only in life and movement that a mass of stone cannot show.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook