About

This Western Canon classic – called "German art's Sistine Chapel" by mega-critic Jonathan Jones – is as hyper-violent as a Quentin Tarantino movie while taking a graphic novel approach to telling the story of Christ's sacrifice.

The altarpiece was executed between 1512 and 1516 as a commission from the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim. The monks at the monastery cared for peasants and social pariahs suffering from diseases that affected the skin, notably plague and the condition once known as St. Anthony’s Fire. Today this condition is recognized as poisoning from a fungus known as ergot, caused by eating bread made from rye, and uncommonly other grains, contaminated due to unsanitary storage. Untreated ergot poisoning, also known as ergotism, results in one of two conditions: Convulsive ergotism and gangrenous ergotism. The former attacks the nervous system and causes limbs to convulse and painfully contort, the neck to twist, and vivid hallucinations. The latter restricts blood flow to the arms and legs leading to infections which rot and spread without amputation. Experiments by a Swiss scientist in the 1930s to find a medical application for ergot lead to the first synthesized form of LSD.

Monks at Isenheim provided palliative care to patients with ergotism. That is, they offered anti-inflammatory salves, ergot-free bread, and healthy doses of a drink called saint vinage. This last cure was a holy blend of select herbs and relics of Saint Anthony steeped in a fortified wine. The monastery's medical mission resulted in a healthy bank account which the monks used in part to acquire many marvelous artworks. The collection became a hazard for the monastery in later years. The Isenheim altarpiece was removed from the monastery, along with many other treasures, with the outbreak of Revolution in 1792. It was removed to a local branch of the French national library to preserve it from lawless looters. Today the altarpiece is displayed at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar.

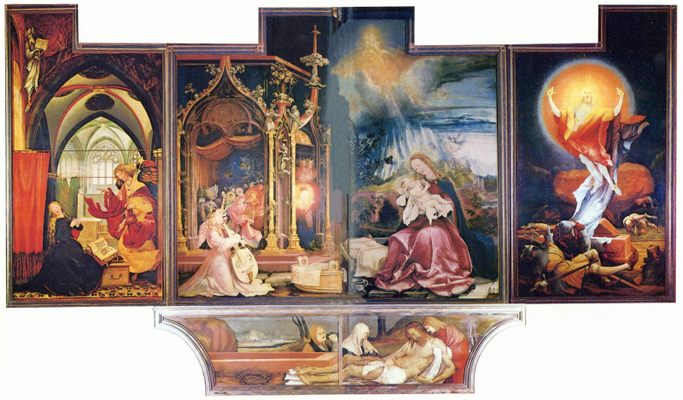

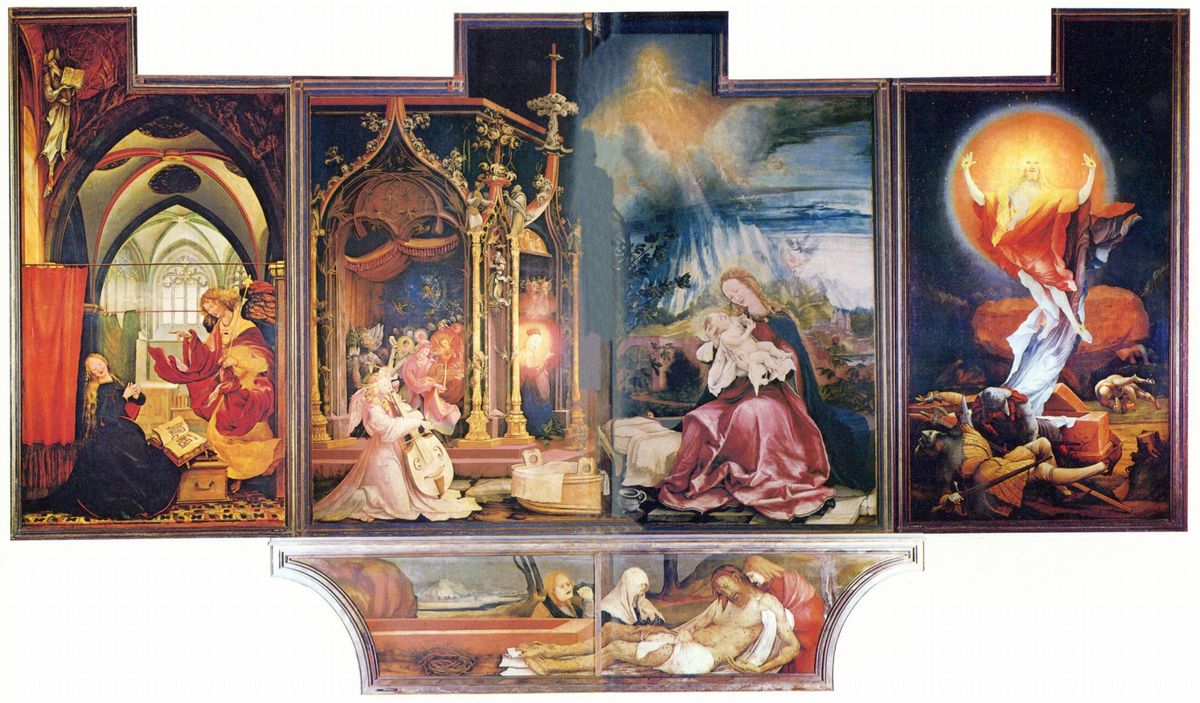

The imagery and figures on the altarpiece show the mission of the monks and aid in their hippocratic efforts. The altarpiece is organized as a polyptych, which means there are at least three painted and hinged panels that open and reveal another painted panel underneath. The panels and wings are painted by Matthias Grünewald while the sculptor Nicalus of Haguenau provided wooden figures for display at the work's heart.

The closed polyptych shows the famous view of a horrific, gangrenous, and corpse-like Christ suffering on the cross with a devastated Mother Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Apostle John on one side and a somewhat sassy-looking John the Baptist on the other. Golden script is set above the Baptist's head that translates as "He must increase, but I must decrease," which is an obvious wink to the viewer that the sore-covered Christ is definitely the God we're expecting to rise and conquer death. There's also the cuddly lamb of the Eucharist at Christ's feet, replete with a cartoonish spurt of Holy Blood coursing from the lamb's chest into a goblet, further visualizing the sacrificial aspect of the Passion while reminding viewers of their own salvation. Beneath the panels is a scene of Christ's entombment and on either side are wings that depict the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian and Saint Anthony being harassed and/or tempted by a monster. Both saints were known as healers. While the connection to Saint Anthony is obvious at this point, Saint Sebastian was the big intercessor in heaven for anyone suffering from plague.

Grünewald's Crucifixion was opened on feasts celebrating the Virgin Mary to reveal the panels and wings beneath. The middle section of the polyptych reveal a left wing and central panel which tell the story of Mary. The wing depicts the Annunciation, when the Virgin is informed that she will bear God's Son. The panel follows that up with a symphony of angels celebrating the birth of Jesus, swaddled in Mary's arms. At right, Jesus peaces out of the tomb to bring salvation to the world o'er.

If they were really lucky, pilgrims and those suffering ergotism might see this middle panel opened view the final scene. The final center panel is adorned with sculptures by Nicalus. Saint Anthony sits in glory at the sculpture's center, flanked on either side by small figures providing offerings. Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome are on the left and right, respectively. These were two of the four widely recognized great theologians of the early church. Beneath the central sculptures are depictions of Christ and the Twelve Apostles imbuing the altarpiece with great spiritual authority. The final left and right panels are both by Grünewald. The left shows a meeting between Saint Anthony and the ascetic Saint Paul the Hermit. At their feet, since they're so wise and all, grow herbs used in saint vinage. At right, Saint Anthony is tempted to disavow God by a host of Hieronymus Bosch-inspired monsters tearing him limb from limb. One of the monsters lazes about the bottom left corner of the wing, exposing a distended belly and bare arms and legs covered in lesions which mimic gangrenous ergotism. It is possible the lazy demon was used as a kind of diagnostic tool by novice or uncertain monks trying to aid new patients.

The Isenheim Altarpiece has provided inspiration to numerous thinkers and canonized artists. The philosopher Elias Canetti once tried to stay in the Unterlinden beyond closing time, writing in a memoir that, "I wished for invisibility so that I might spend the night there." The altarpiece played a significant role in goading composer Paul Hindemith to create his opera about Grünewald. Pablo Picasso even took inspiration, creating an entire series of pen-and-ink compositions that riffed on the Crucifixion.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

April 18, 2017

Sources

- http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/g/grunewal/2isenhei/index.html

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-paintings/isenheim-altarpiece.htm

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/07/travel/isenheim-altarpiece-musee-unterlinden.html?_r=0

- https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/renaissance-art-europe-ap/a/grnewald-isenheim-altarpiece

- http://www.stanleymeisler.com/smithsonian/smithsonian-1999-09-grunewald.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isenheim_Altarpiece

- https://www.erowid.org/general/conferences/conference_mindstates4_nichols.shtml

- http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/wong/BOT135/LECT12.HTM

- http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-paintings/isenheim-altarpiece.htm

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/dec/12/art

- http://www.musee-unterlinden.com/en/collections/the-isenheim-altarpiece/

- picasso + isenheim altarpiece