About

The Basque Country (Euskal Herria) is not independent, but rather an ethnocultural division that spreads across seven historical provinces between two independent European nations. The provinces of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Nafarroa Beherea (or Lower Navarre) are in France; while Araba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Nafarroa Garaia (or Upper Navarre) are in Spain.

The symbolic "eighth province" of Euskadi is its diaspora, found around the world. North and South America have been the destination for several migrant movements from France and Spain, so it makes perfect sense that a large portion of the Basques' Eighth can be found in this hemisphere.

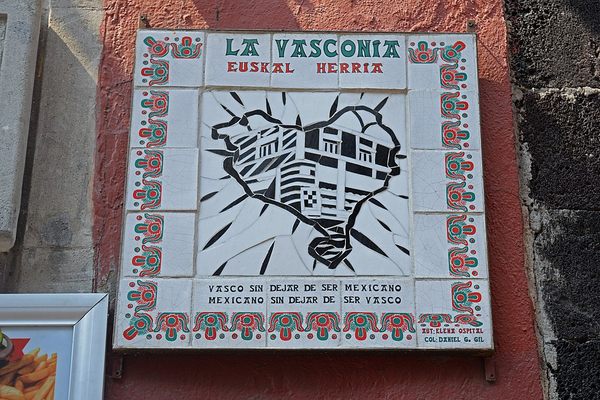

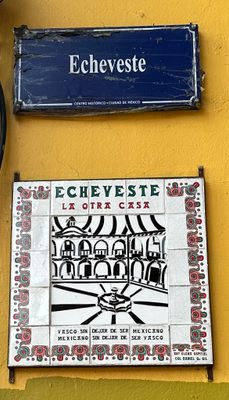

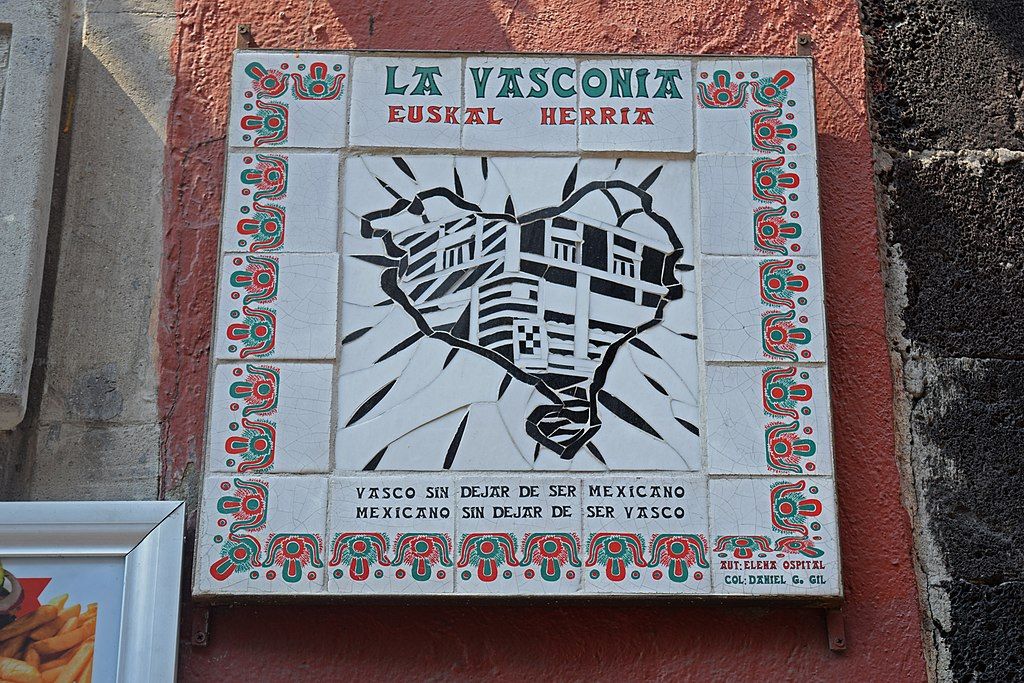

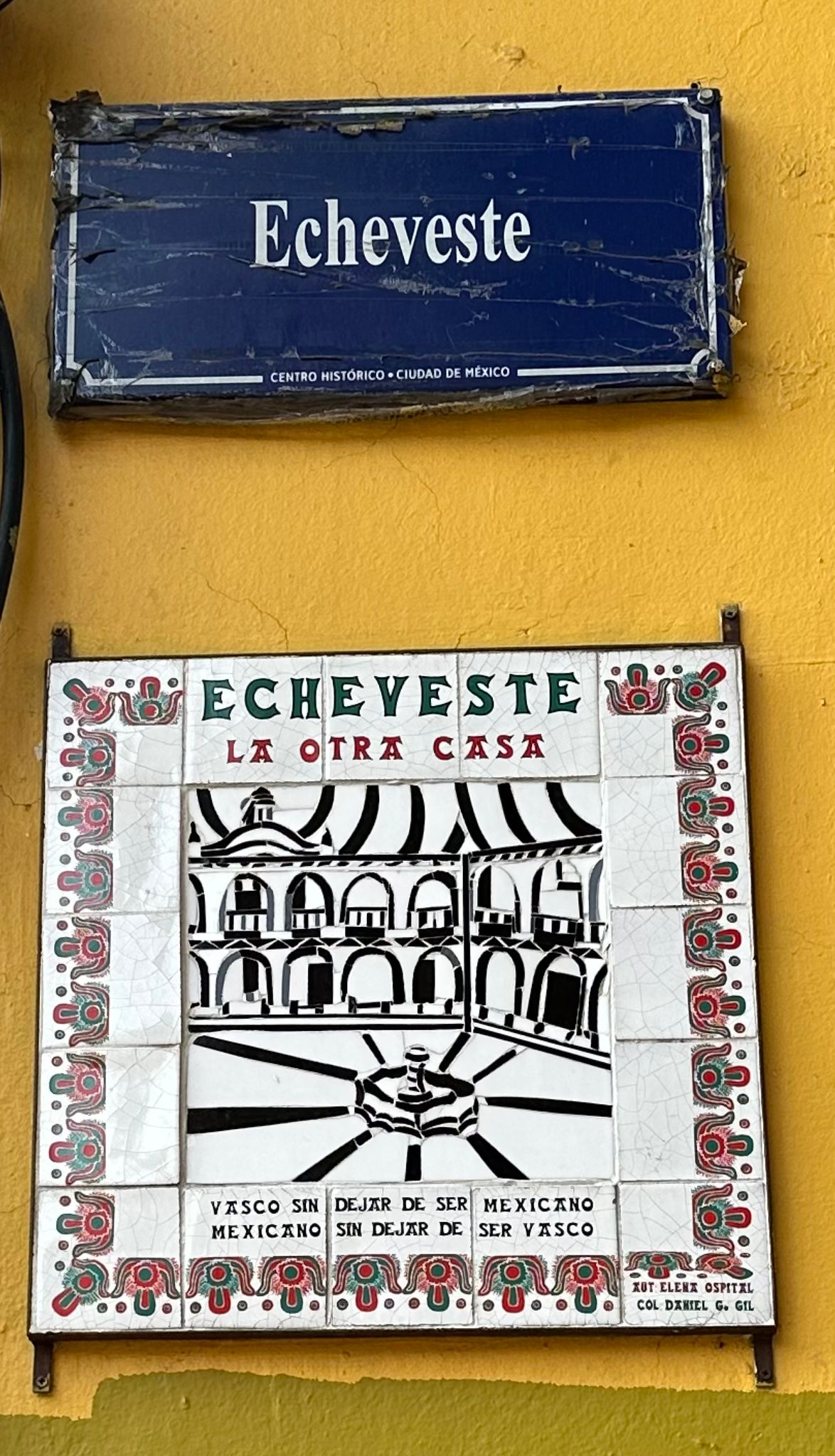

In the United States, the best example is probably the Basque Block of Boise, Idaho. Meanwhile, in Mexico City, a series of eight mosaic plaques represents one of the clearest celebrations of these people's contributions to their new home. They are the work of Elena Ospital, who was born in the community of Saint-Jean-de-Luz in Lapurdi, and Daniel González Gil (credited as Daniel G. Gil on the works).

One of the plaques is located on the pedestrianized street of Echeveste, meaning "The Other House" in Basque. Francisco de Echeveste, born in Gipuzkoa, was involved in military and economic affairs of the mid-18th century colony of New Spain. He was crucial in the funding of the Colegio de Vizcaínas (named after the Bay of Biscay), which is located close to this street. The mosaic shows the Colegio's patio.

Another can be found on Tacuba Street, outside a bakery called La Vasconia. Its translation of "Euskal Herria" represents the Basque Country itself. Vasconia was the name of an early 7th-century Duchy, which occupies much of the same territory as modern-day Basque Country. The mosaic shows an outline of the territory, which is often referred to in Spanish as "Vasconia."

Along the street named after Simón Bolívar, one of the most important liberators of the Americas, you can find another plaque. Fighting in South America, Bolívar lead the independence movements of several countries, and modern-day Bolivia is named after him. The surname is of Basque origin, and means "Valley of the Windmills".

Another one outside a bakery, the Pastelería Elizondo, which is another common surname that means "Next to the Church," as well as a Basque town. The mosaic shows the main church of Elizondo alongside a Mexican-style skull eating some bread.

One on Mina Street, named after Francisco Javier Mina Larrea. Xavier or Xabier Mina (as his name is also spelled following Basque language rules) was born in Otano, Navarre. He fought during the Spanish War of Independence against France, and would later join the Mexican War of Independence, this time against Spain. Mina is honored on both sides of the Atlantic, as there is a sculpture dedicated to him in Otano. The mosaic is a portrait.

Along Independencia Street, a mosaic has the Basque word "Independentzia." Both names mean independence, and its subtitle defines this as the "struggle for self-determination," an important political point for the Basque people in their homeland. A star with the ikurrina/ikurriña, the Basque flag, is represented in the picture.

One plaque can be found on a street named after colonial painter José de Alcíbar, whose surname means "Valley of the Alders." Of the plaques on display, this is likely the most damaged, seemingly due to vandalism. It formerly depicted the foliage of an alder tree, although only a few leaves remain.

The only one no longer on display (as of March 2022) was located outside a shoe store called Gurea. The name means "Ours" and, following the store's closure, the owner liked the plaque so much that he had it removed and kept it. It depicted the lauburu, or Basque cross, which was also the logo of the shoe store.

All plaques have the same ceramic tiled frame with the phrase "Vasco sin dejar de ser mexicano, mexicano sin dejar de ser vasco" ("Basque without ceasing to be Mexican, Mexican without ceasing to be Basque"). Inside this frame, a black-and-white glass mosaic depicts the images listed above. The project was initiated around 2012 with assistance from the now-defunct Mexico City governmental institution SEDEREC (Secretariat for Rural Development and Equity for Communities).

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The existing plaques can all be seen at all times since they are located on the outer walls of their respective buildings. Ospital and González continue to use their craft in glasswork in the form of the jewelry project MosaiDeko.

Yucatan: Astronomy, Pyramids & Mayan Legends

Mayan legends, ancient craters, lost cities, and stunning constellations.

Book NowPublished

May 16, 2022

Sources

- http://www.orreagafundazioa.eus/homenaje-en-otano-al-libertador-navarro-xabier-mina-en-el-bicentenario-de-su-muerte/

- https://mosaideko.com/pages/conocenos

- https://www.francebleu.fr/emissions/basqu-en-reseau/elena-ospital-mexico-0

- https://euskalkultura.eus/espanol/noticias/el-encuentro-cultural-mexico-y-euskadi-un-viaje-de-ida-y-vuelta-tendra-lugar-el-26-de-noviembre

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9TuRY_h1Q0

- http://www.orreagafundazioa.eus/homenaje-en-otano-al-libertador-navarro-xabier-mina-en-el-bicentenario-de-su-muerte/

- https://mosaideko.com/pages/conocenos

- https://www.francebleu.fr/emissions/basqu-en-reseau/elena-ospital-mexico-0

- https://euskalkultura.eus/espanol/noticias/el-encuentro-cultural-mexico-y-euskadi-un-viaje-de-ida-y-vuelta-tendra-lugar-el-26-de-noviembre

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9TuRY_h1Q0