About

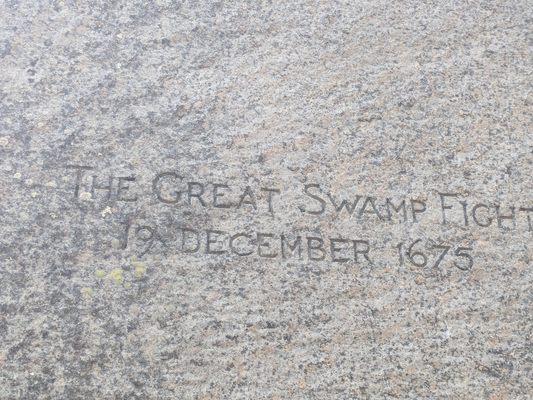

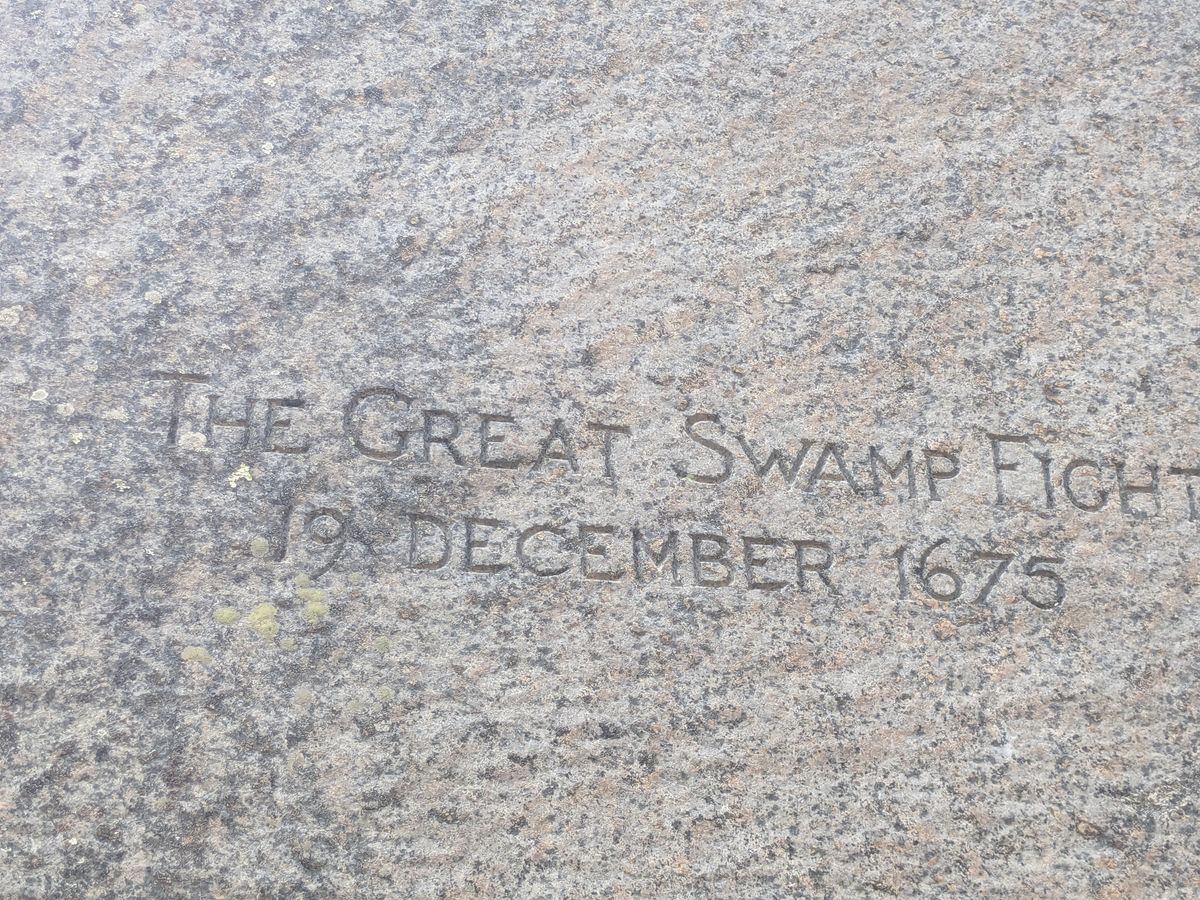

On December 19, 1675, Native American and Colonial forces clashed in a battle that would go down in history as the “Great Swamp Fight.” Today, this monument pays tribute to the brave soldiers on both sides of the battle.

During the winter of 1675, King Philip’s War was raging in New England. The war was named after Metacomet, the chief of the Pokanoket (Wampanoag) tribe, who was called “King Philip” by early Anglo settlers. His father, Massasoit, had befriended the first settlers of Plymouth Colony who had arrived on the Mayflower in 1620. In the early years, the settlers and the Pokanoket (Wampanoag) maintained a relationship based in the trading of English goods for Indian lands, furs and other natural resources.

In 1661, after the death of Massasiot, his eldest son, Wamsutta, (referred to as Alexander) became sachem. Wamsutta died in 1662 under mysterious circumstances while visiting the Puritan settlement to discuss growing tensions between the natives and the settlers. Metacomet (Philip) then rose to sachem. Tensions became further inflamed with the trial and execution of three natives in June of 1675 accused of the murder of John Sassamon, a “praying Indian” loyal to the settlers.

Philip, angered by the English for their violation of treaties and agreements, and fearful that the natives would soon lose claim to all lands, built a coalition of various Native tribes. by the fall of 1675 they began to skirmish with settlers and attacked settlements in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

The nearby Narragansett tribe attempted to remain neutral, and in October of 1675, the Chief Sachem of the Narragansett tribe, Conanchet, traveled to Boston to pledge neutrality in the conflict. However, he did not respond to demands that he refuse to offer refuge to any Wampanoag’s seeking protection and that he immediately hand over any Wampanoag’s (including noncombatant women, children, and the sick and elderly) living among the Narragansett, believed to be sheltered in the Great Swamp.

The Puritan forces of the Confederacy of New England used this refusal as justification to assemble an army to strike the neutral Narragansett at their fort in the middle of a swamp near Kingston, Rhode Island. The Narragansett had learned that the Puritan army from Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies, assembled at Smith’s Castle, was to meet up with troops arriving from Connecticut at Jeriah Bull’s Garrison to launch an attack on the Narragansett encampment.

On December 15th, warriors from the tribe attacked the nearby Jeriah Bull’s Garrison, killing at least 15 people. Finding the garrison in ruins the next day, the Connecticut troops were forced to march miles further north to assemble at Smith’s Castle with the troops from Plymouth and Massachusetts. On the freezing, stormy day of December 19th, Colonial forces marched from Smith’s Castle and attacked the over 1,000 Narragansett at the fort.

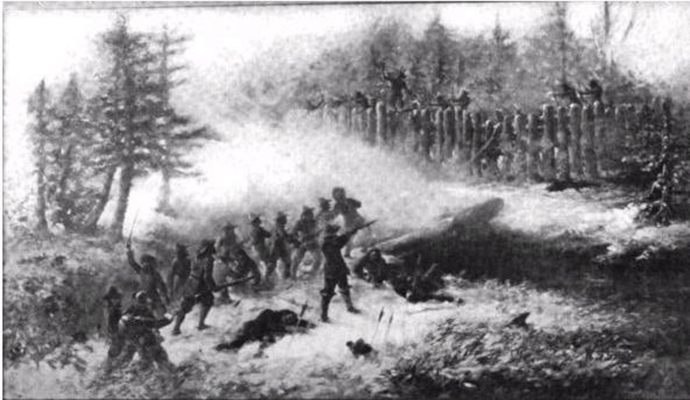

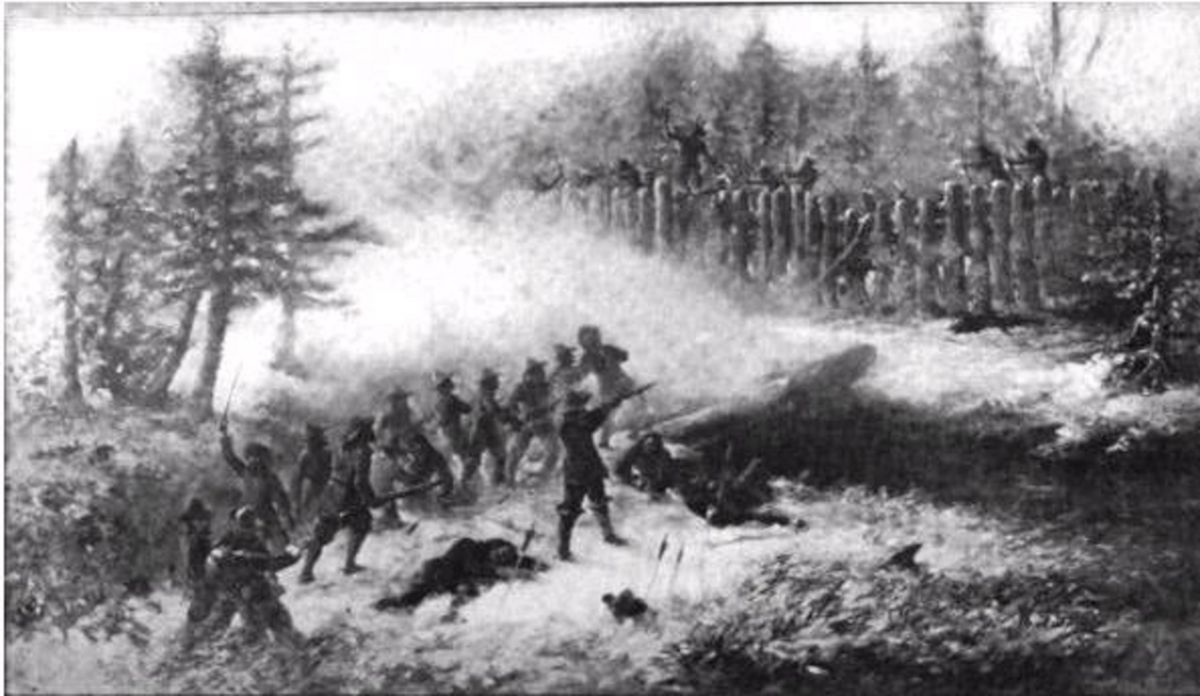

It has been estimated that approximately 600 Natives (including women and children) were massacred, as the colonial forces bridged the defensive barricades, burned the wigwams within and drove the natives from the fort. Many of the Natives escaped into the bitterly cold swamp that surrounded them, some eventually died due to their wounds, exposure to the cold and starvation. Over 150 Colonial militia men were killed or wounded, some dying during the freezing cold march back to Smith’s Castle. Not surprisingly, after the battle, the Narragansett tribe fully joined King Philip’s coalition.

The Great Swamp Battle was a crucial turning point in the war. It forced both the neutral Narragansett tribe and the colony of Rhode Island (which also wished to remain neutral) into the war. By the end of March 1676, nearly all of Rhode Island had been set ablaze in retaliation for the Great Swamp Massacre, and nearly all of the colonists that survived the initial Native attacks, retreated to the fortified settlement on Aquidneck Island. The colonial forces eventually killed Canonchet, the chief of the Narragansett, and in August of 1676, ambushed and killed King Philip. The death of Philip ended the war. The tribes of New England never recovered and it took decades for the devastated settlements in Rhode Island, Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies to be re-inhabited and to thrive again.

In 1906, representatives of both the Narragansett and the Colonists came together to dedicate this monument at a spot believed to be the battle site. The rain poured down as three Narragansett women unveiled the inscribed stone, which reads:

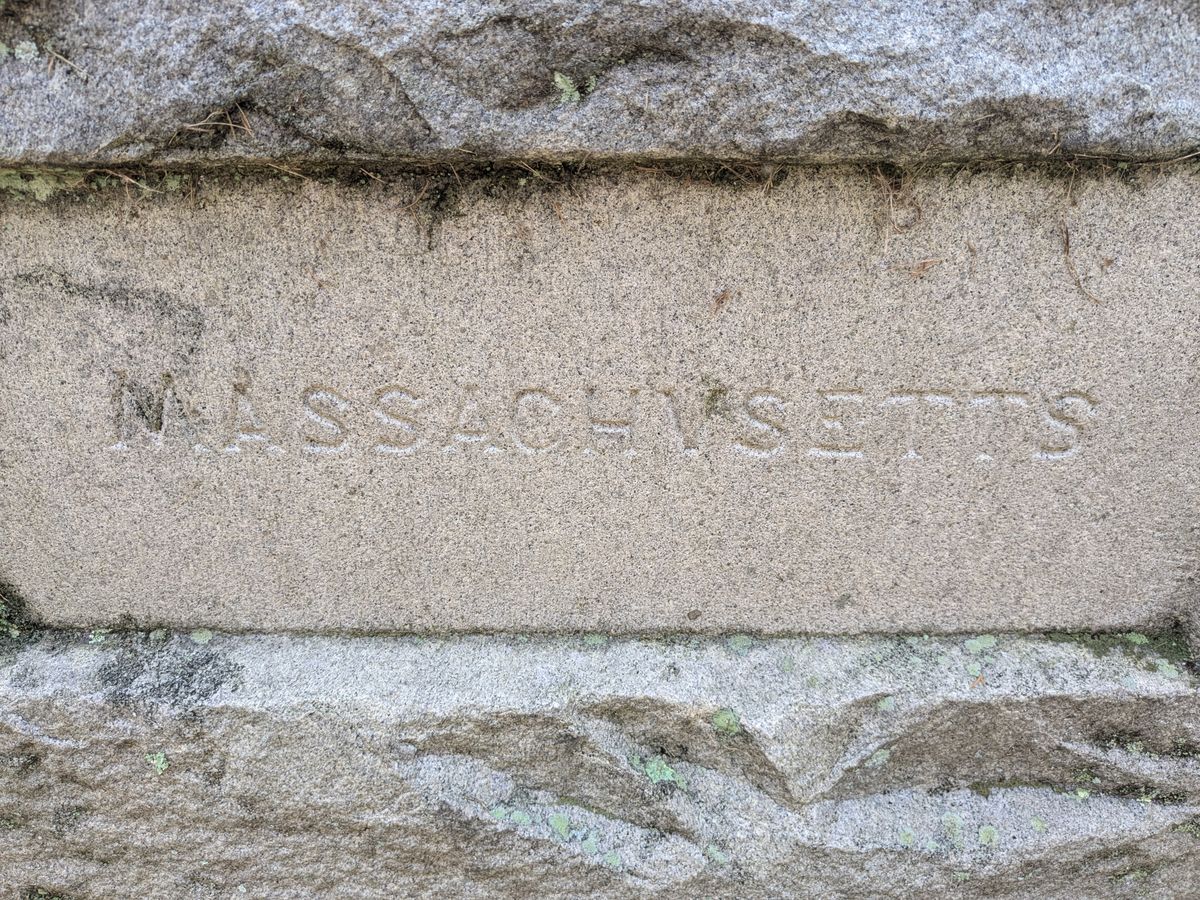

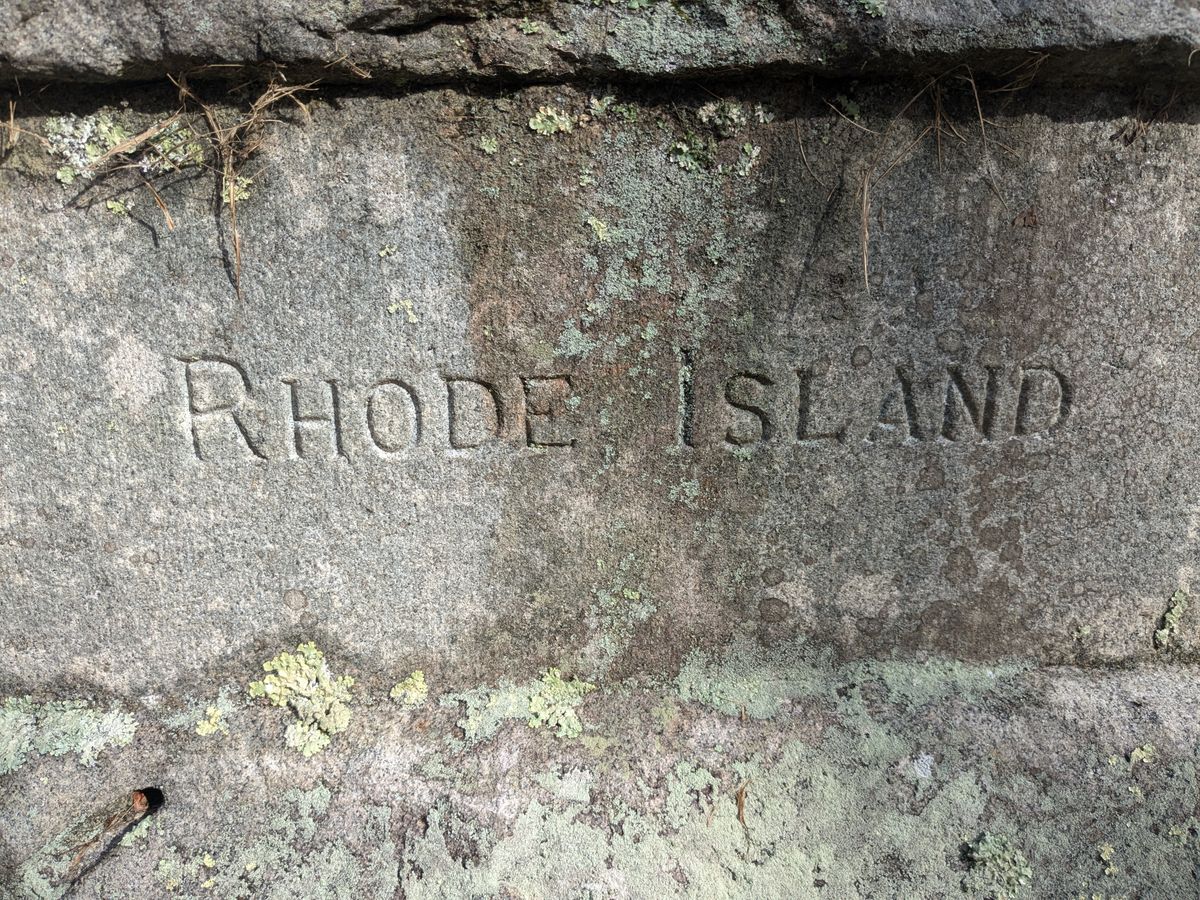

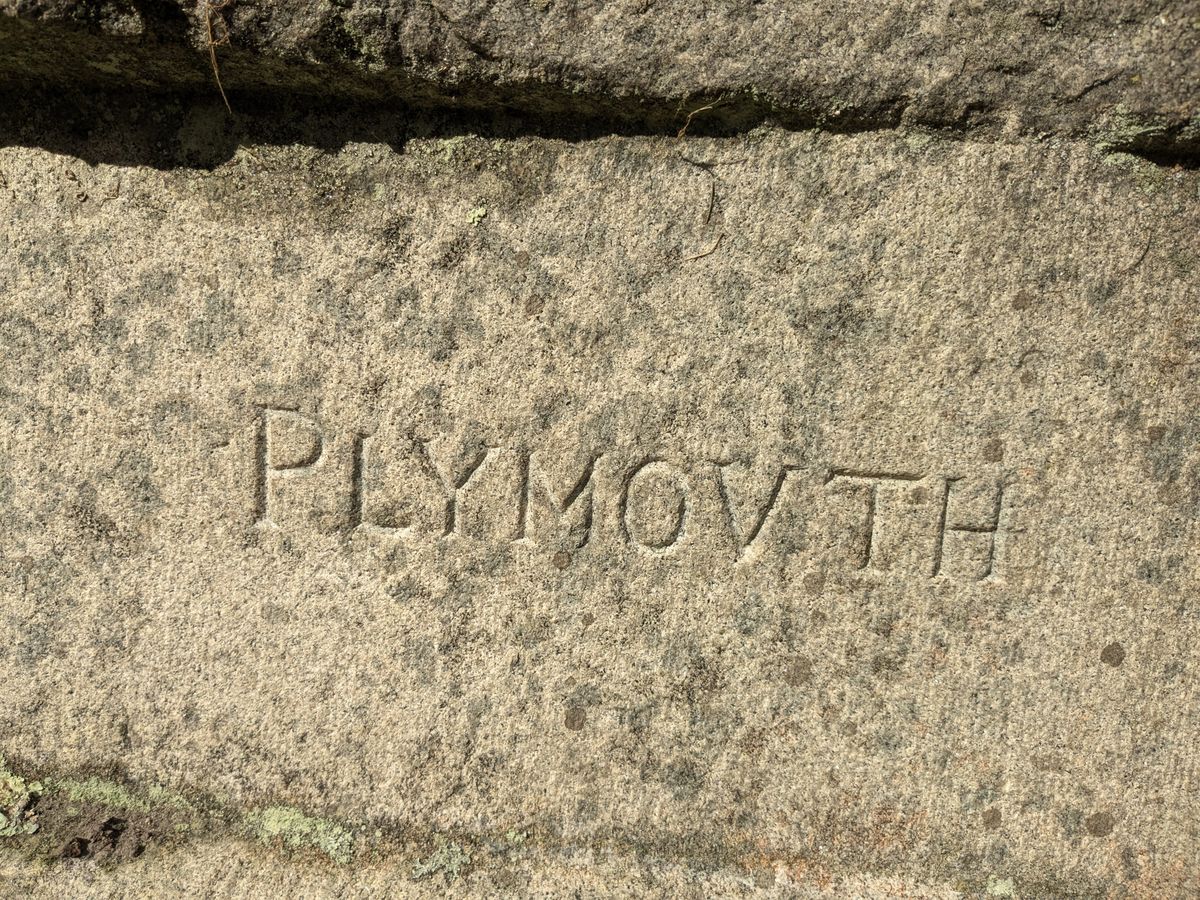

“Attacked within their fort upon this island, the Narragansett Indians made their last stand in King Philip’s War and were crushed by the united forces of the Massachusetts Connecticut and Plymouth Colonies in the “Great Swamp Fight,” Sunday, 19 December, 1675.This record was placed by the Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars, 1906.”

Today, the memorial is a quick mile-and-a-half hike for pedestrians, though the road leading to the site is closed to cars. The tree and swamp surrounded memorial features a rough stone shaft surrounded by low stone markers. Standing in this peaceful, lovely spot, the brutal battle that once raged here seems very far away.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

November 17, 2015

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Swamp_Fight

- https://trailsandwalksri.wordpress.com/category/great-swamp-monument/

- http://www.churbuck.com/wordpress/2007/12/the-great-swamp-fight-332-years-ago-today/

- Title: King Philip's war: based on the archives and records of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Rhode Island and Connecticut, and contemporary letters and accounts, with biographical and topographical notes Author: Ellis, George William Morris, John Emery

- Title: A Record of the ceremony and oration on the occasion of the unveiling of the monument commemorating the Great Swamp fight, December 19, 1675, in the Narragansett country, Rhode Island Author: Rowland Gibson Hazard 1855-1918.; Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

- Rhode Tour - Princess Red Wing (rhodetour.org)

- Narragansett Indian Tribe - Great Swamp Memorial Pilgrimage Ceremonies (narragansettindiannation.org)