The U.S. Government Is Begging You to Destroy Moss Balls

Zebra mussels showed up in imported aquarium accessories across 32 states. Ecologists want your help killing them.

There are several ways to wreck a moss ball. You might not want to, at first, because they’re quite charming, as far as aquarium accessories go—vivid green and damply hairy, like a Muppet that’s been through the wash. But if you choose to be merciless, you can pick from several modes of attack. You could seal it in a plastic bag and banish it to the freezer. You could submerge it in screaming-hot water for 60 seconds. You could dunk it in diluted bleach for 10 minutes, or straight-up vinegar for 20. Any of these approaches will also kill the real target: unwanted creatures bedding down on the small, fuzzy spheres.

It’s sadism in the name of conservation. Pet stores in 32 American states were recently found to be selling moss balls studded with zebra mussels, Dreissena polymorpha, and the U.S. government wants the mollusks gone, one mangled moss ball at a time.

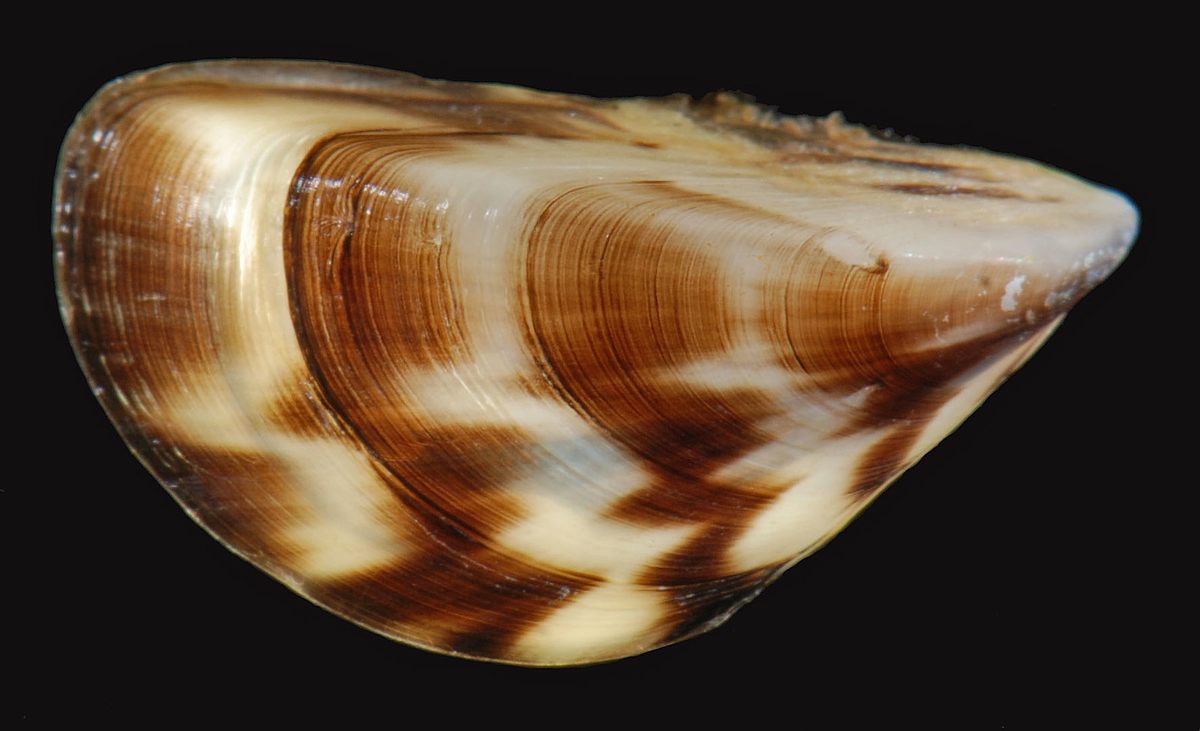

Zebra mussels, named for the zigs and zags on their almond-sized shells, are native to Eurasia, and are thought to have first arrived in North America in the late 1980s as stowaways on ships lumbering across the Great Lakes. The mussels probably sloshed around in ballast water, stored to stabilize an empty ship and released before it’s loaded with cargo.

Once the mussels enter a waterway, they have no trouble moving around it. Sperm and eggs drift freely, and females can lay more than a million in a single season. Larvae, known as veligers, are visible only under magnification. As adults, they tussle for space, encrusting water pipes and the hulls of boats, and glomming on to their neighbors. In lakes and rivers, zebra mussels filter vast quantities of water and siphon the nutrients for themselves. Several hundred thousand can crowd a single square meter, and they’re persistent: They hide in tangles of aquatic plants snagged on motors, can colonize essentially any hard surface, and are able to survive outside the water for several days.

Zebra mussels are “pretty much bad news all around,” says Ceci Weibert, an aquatic invasive species senior program specialist with the Great Lakes Commission. “They filled this niche and they don’t have any predators. They’re taking something out of the food web, and not putting anything back in.”

By 1990, notes United States Geological Survey (USGS) fishery biologist Amy Benson in a report, zebra mussels had been spotted in all five Great Lakes. By 2020, the mussels had been seen in more than 600 lakes and reservoirs around the country, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, one of several agencies that has tried for decades to stop the spread. Around 30 years ago, to keep track of sightings of zebra mussels and other introduced species, the USGS set up the Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. That’s how Wesley Daniel, the database coordinator and a fisheries biologist at the USGS, recently learned that a zebra mussel had turned up on an imported moss ball in a Seattle Petco.

“I was shocked,” Daniel says. Other non-native species have been known to hitchhike on plants—salamanders from the northwest, for instance, have been ushered eastward on Christmas trees—but “we never expected zebra mussels to travel through aquarium plants,” Daniel says. “It’s not a pathway we had ever considered.”

An employee at the Seattle store uploaded the sighting February 25. By March 2, Daniel had learned about the post, reviewed some photos, rallied colleagues at the state and federal level, and canvassed for the little green blobs in Gainesville, Florida, where he lives. At the first pet store he surveyed, Daniel found an adult zebra mussel clinging to a moss ball. That made him realize the Seattle sighting wasn’t “a weird fluke,” he says. “If they’re in Washington and Florida, I’m assuming they’re going to be distributed everywhere in between.”

Daniel showed the pet store manager how to kill the freshwater interloper by dunking it in super-salty water, and they removed the moss balls from the shelves. Still, by March 8, the USGS reported mussel sightings in moss balls in Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, Washington, and Wyoming—with more states added since. Officials are investigating what Daniel refers to as the “chain of custody,” trying to determine whether the moss balls all came from a single producer, likely a wholesaler based in Ukraine, or from several sources. Meanwhile, with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other partners, the USGS issued guidance for going ham on the moss balls to quash the new invasion—that’s where all the bleaching, boiling, freezing, and other pummeling comes in. Afterwards, the brutalized ball should end up in the trash, in a sealed bag.

Introductions from home aquaria aren’t the most common vector for species entering waterways such as the Great Lakes, but “they do happen,” says Christine Mayer, an aquatic ecologist at the University of Toledo. “Especially with fish—people don’t want to kill them. People don’t feel so bad about putting a plant in the compost, but they’re not sure they know how to humanely euthanize a fish.” Mayer says that ecologists sampling in the Great Lakes will sometimes come across a goldfish, either freed from a fishbowl or descended from others gone feral.

A preemptive strike is the best way to keep zebra mussel populations small, because established communities are incredibly difficult to eradicate. “Everyone who works with invasive species says prevention is better than cure,” Mayer says. “Keeping things out is cheaper, easier, and better than trying to kill them once they’re there.”

Introductions from large ships aren’t such a major issue anymore, because there are now procedures about how, where, and when ballast water can be dumped, says Eva Enders, a research scientist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada who has studied the mussels’ muscling through Lake Winnipeg, in Manitoba. Now, Enders says, “the risk that remains is inland—the transport by small leisure or recreational boats from lake to lake, river to river.” To aid in prevention, ecologists, naturalists, and others around the Great Lakes region have encouraged boaters to inspect their hulls and motors and thoroughly drain and dry water-holding compartments between outings.

It’s hard to picture a future in which waterways that are suffused with the mussels are ever fully free of them. “The Great Lakes are kinda…they’re already a thing,” Mayer says. That’s not the case everywhere, though, and more recent efforts have focused on stifling invasive zebra mussels in the western U.S., where they haven’t yet claimed as much turf. Groups such as the Invasive Mussel Collaborative, which works in partnership with the Great Lakes Commission, USGS, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and others, share tactics for snuffing out small populations. In New York’s Lake George, for example, a team successfully evicted a fledgling mussel population by quarantining the entire lake and dispatching divers to remove them manually.

Other strategies include pumping carbon dioxide into the water column, which suffocates the mussels inside it, and laying tarp-like benthic mats on mussel-studded bottoms, barricading the creatures from oxygen, light, and food. Several states have “decontamination stations,” where boats are inspected and cleaned, Weibert says. In Alberta, Canada, mussel-sniffing dogs are trotted out at highway checkpoints, Enders notes. USGS staff are currently adapting a test, initially developed for invasive carp, to suss out genetic evidence of zebra mussels in the water; Daniel thinks it could be up and running in the next several months.

But for now, ecologists really want your help preventing new spreads—and that involves unleashing some hellfire fury on moss balls.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook