A Town Named Asbestos Once Produced Most of the World’s Asbestos Supply

Asbestos mining in Canada stopped only in the past decade.

Hidden in old buildings and under streets, asbestos—once thought of as a “miracle mineral”—is always lurking. Though today it might seem like a relic of the past, under new rules from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. government could approve new uses of asbestos in consumer products going forward, reports Fast Company.

There are still places where asbestos mining is a notable industry: Canada’s asbestos mines—including the mine at Asbestos, Quebec, once the largest in the world—only closed within the last 10 years, and in Russia, the town of Asbest is still a major center of asbestos production.

Asbestos has many strange properties and has been incorporated into manmade products going back thousands of years. Manufactured, it often comes into human environments as a textile or a dangerous powder, but in nature it appears as six different types of natural silicates. Part of what makes it uniquely useful is how its crystals form, into tiny, thin fibers. It can be woven into fabric, it’s resistant to fire, it dampens sound.

Modern asbestos mining started in the 19th century, and Canada became one of the leading producers of asbestos early on. In the 1850s, significant deposits of chrysotile, the most commonly used form of asbestos, were found in Thetford, Quebec, south of Quebec City. By the end of the 19th century, the Jeffrey Mine, about 50 miles southwest, had also become a major source of asbestos, and when workers settled near the mine, they called their town Asbestos.

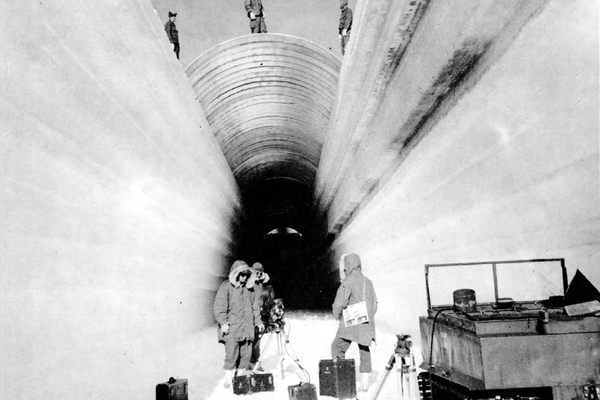

At the height of asbestos mining, around the 1970s, there were dozens of asbestos mines in the U.S., but about half of the asbestos used around the world was coming from this one mine in Canada. Usually, asbestos mining required several long and linear mines, but because of a rare circular pattern in this deposit, the miners could simply create a pit mine and start digging out the mineral. Over time, as the pit expanded, the workers had to move their town to keep it away from the expanding circumference of the mine.

Of course, there were problems with asbestos mining. By the middle of the 20th century, the health effects of breathing in asbestos fibers, which can cause cancer, were becoming well known. Environmental agencies starting controlling its use more tightly, and workers sickened by their jobs started demanding compensation and greater protections. Still, the mines themselves were slow to close, as there was still demand in India and other parts of the world for the product. The last asbestos mine in the U.S. closed in 2002; Canada shut down its asbestos mines in 2012.

Today, the town of Asbestos, Quebec, is still tied to its mineral legacy. A local brewery has named its beers Mineur (Miner); Spello, a mining term, and L’Or Blanc—white gold, as asbestos was known. The brewery also made a pale ale with water drawn from the bottom of the mine. They tested the water, one brewer told the BBC, and it was “perfect.” There’s also an Asbestos Mineral Museum, and it’s possible to tour the old mine or see it from a platform at the museum.

In Asbest, Russia, though, mining is ongoing. “When I work in the garden, I notice asbestos dust on my raspberries,” one resident told the New York Times in 2013. Regulators there consider it safe when properly handled, they told the Times. Most of the asbestos used in the U.S. in recent years has come from Brazil, but now those mines are shutting, too. Russia could become an asbestos supplier to the U.S., and the people of Asbest are looking forward to it. In the U.S., asbestos is still used in roofing materials and floor tiles, for fire protections, and in other consumer products. It’s a small market and, even under the new rules, unlikely to grow fast. But when your town is named for a toxic substance that many people are afraid to be around at all, you look for business anywhere you can.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook