What a Blanket Made With Dog Hair Can Tell Us About Indigenous Communities in the Pacific Northwest

The Coast Salish wool dog has been extinct for a little over a century.

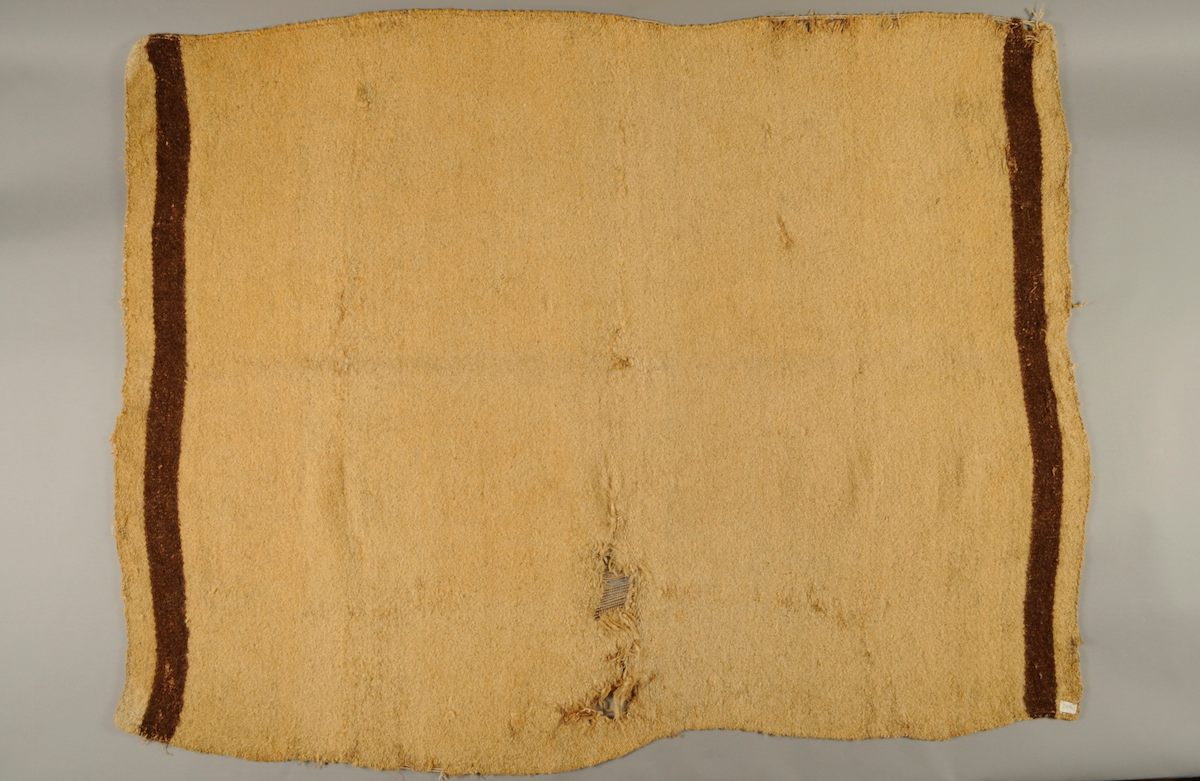

At the Burke Museum in Seattle, Washington, there rests a white blanket with two reddish-brown stripes running down the sides. It’s more fuzzy than fluffy, and a gaping tear in the outer layer exposes the horizontal threads woven beneath. Those threads are made of materials including hemp, linen, goat hair, and the hair of the Coast Salish wool dog, also known as the woolly dog, which has been extinct for over a century.

Few objects survived the encroachment of settlers upon Coast Salish people—a group of related tribes native to an area ranging from the Puget Sound up to the middle of Vancouver Island in British Columbia—and their land, so remnants like this blanket are precious. “Something created by the hands of a weaver in your community … that’s an important kind of connection that goes far beyond what we can put in a museum catalog,” says Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, a curator at the Burke Museum.

Lydia Sigo is a Suquamish tribal member and the curator and archivist at the Suquamish Museum. Suquamish, Washington, is seated across the Puget Sound from Seattle and just north of Bainbridge Island, where, Sigo says, woolly dogs were kept for over a thousand years.

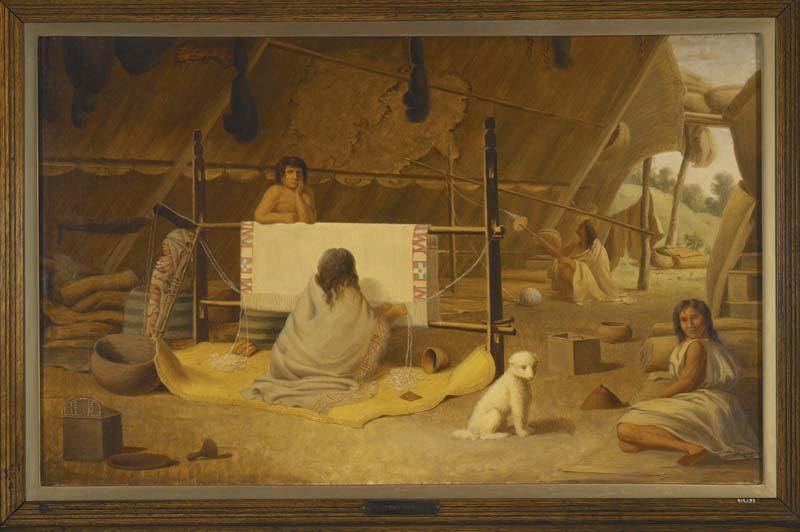

Because their prized white hair was the product of a recessive trait, the dogs were kept on islands including Bainbridge and Tatoosh—a little thimble of rock jutting up from the sea at the westernmost tip of northern Washington just below Vancouver Island—so they would be isolated from hunting dogs and other canines in the village. The Coast Salish people fed them a bounty of dried salmon, which kept the canines glossy-coated over the winter months. Before the dogs were shorn with sharpened mussels, their fur was cleaned of dirt and debris with white clay or diatomaceous earth. Those hairs were turned into a fluffy, tangled mass, then spun into yarn together with fibers of plants, such as stinging nettle or Indian hemp; plant fluff from fireweed, cottonwood, and cattail fluff; mountain goat hair; and feather materials, such as duck down.

Out of those materials came highly-prized blankets. Blankets were for ceremonial use—they were used at marriages, naming ceremonies, and initiations into Salish religious practice—and also represented wealth and generosity. “Part of Coast Salish culture is about being a good host … the symbol of wealth is what you give away, not what you keep,” says Sigo. According to S’abadeb / The Gifts, a book about Coast Salish art and culture by Barbara Brotherton, an ultimate example of this principle was the blanket scramble, a free-for-all during which blankets were tossed, often from atop a longhouse, for people to tussle over. The scrambles continued even when blankets became rarer in the 19th century. Then, pieces rather than entire blankets were thrown out, and could be collected to weave into fuller textiles.

Woolly dogs themselves were a highly valuable trade item. “Not everyone had a little wool dog,” says Joey Holmes, who is a member of the Nondalton and Grand Ronde tribes and married into the Suquamish. Holmes began teaching himself to weave as a teenager. “We have this saying now: Our cedar bark clothing was like our jeans and T-shirts and our wool regalia was like our formal wear,” he says.

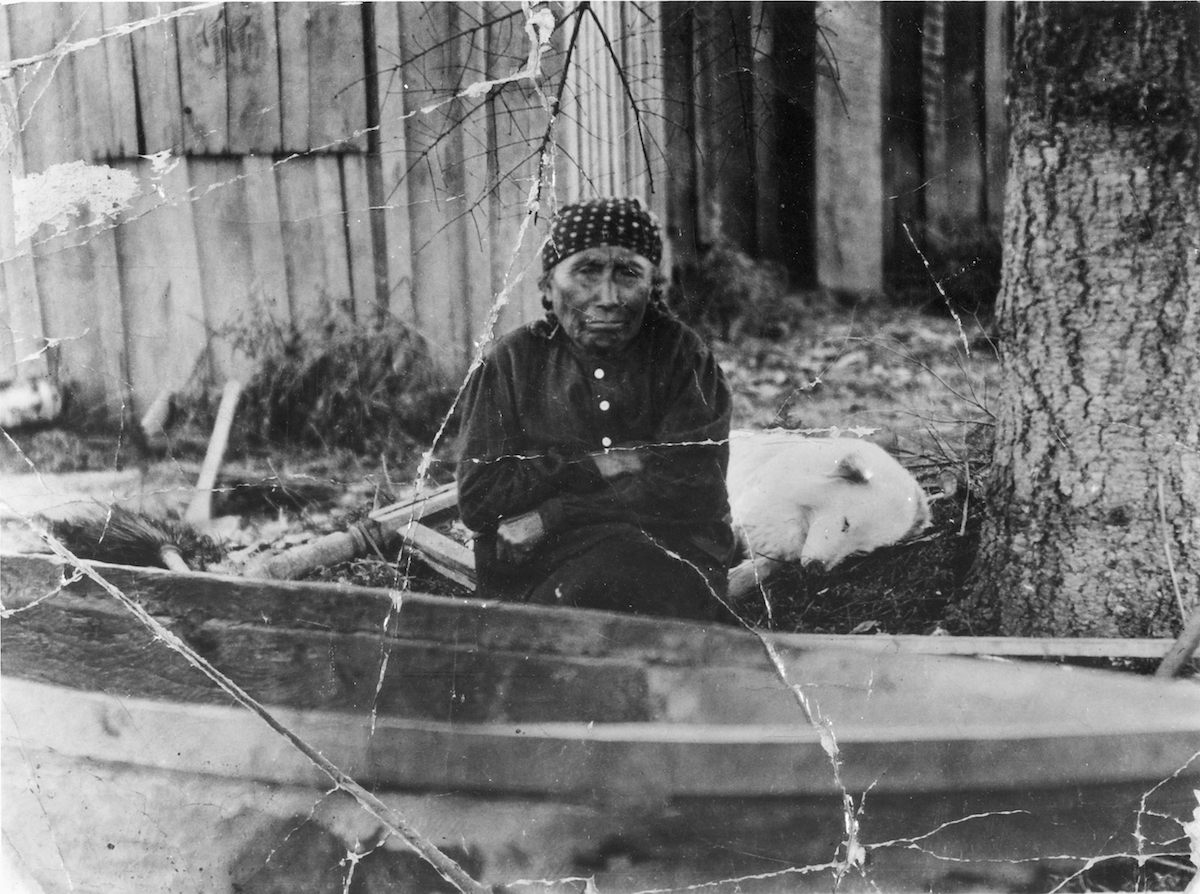

In 2011, Holmes found a mentor in Virginia Adams (her traditional name is šəq̓həblu), a descendant of Mary Adams, a weaver of blankets and baskets who was married to Jack Adams, one of the last Suquamish chiefs. While woolly dogs officially went extinct in the 1870s, the picture below, taken in 1912, shows Mary with her woolly dog Jumbo. It’s unclear from the historical record how Mary raised or obtained Jumbo, but Sigo notes that, “for [Mary] to have a woolly dog in 1912 shows how our tribe fought to keep their culture when the world was changing.”

“Virginia was one of the main people who helped revitalize wool weaving,” says Holmes. She learned and taught the southern Salish style of textile weaving, native to the Puget Sound area. This style utilizes twill weaving, which can be used to make various zig-zag patterns, including herringbone, a pattern seen in the Burke Museum’s woolly dog blanket. When microscopic analysis revealed that the blanket’s threads contained woolly dog hair in 2017, scientists, museum curators, and members of the Coast Salish community gathered to share and celebrate.

The Coast Salish world changed dramatically after contact with Europeans in the late 18th century. By the end of the 19th century, the dogs had disappeared, and so did the entire lifestyle supporting the production of blankets, from access to fishing waters to the freedom to practice potlatch culture.

“A lot of objects left communities under difficult circumstances and our hope is that these can be teachers now for the current generation,” says Bunn-Marcuse. While blanket scrambles and woolly dogs may not have survived, threads of tradition are still being picked up and passed on to weavers like Joey Holmes, and folded into Coast Salish life today.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook