Why Writers Fight Style Guides Over Animal Pronouns

Should a moose be an “it”? Some writers and scientists think creatures deserve better.

Is this owl a who or a that? (Photo: Maurice van Bruggen/CC BY-SA 3.0)

This past February, science writer Brandon Keim wrote a Valentine’s day piece about a pair of pigeons.

The story, which discusses whether pigeons can love, is sweet, thoughtful, and not at all combative. But after sending his draft to editors, Keim was prepared for a showdown. Throughout the story, he had referred to his main characters, a pigeon couple he named Harold and Maude, with humanoid pronouns—he, she, and who. He feared backlash. In an email to a friend, he limbered up: “The customary pronoun for animals is it,” he wrote. “And it’s a custom that deserves to be buried.”

For Keim—who, in addition to his pigeon work, has recently written about dingoes for Wired, dolphins for Medium, and chimpanzees for National Geographic—animal-related pronoun usage is a factual choice, not a grammatical one. “Just as a matter of accuracy of language, it is inaccurate and inappropriate to use the language of inanimacy to describe conscious beings.” What used to be an instinct has become a professional imperative: “I never use ‘it’ to refer to a conscious being,” he says.

Chimpan-hes and chimpan-shes in Gombe. (Photo: Ikiwaner/GNU 1.2)

People have been arguing about the relative personhood of animals at least since the days of Rene “Animals are Automatons” Descartes. But since the mid-20th century, some who want other creatures’ inner workings to be taken seriously have taken a subtler tack, choosing their words carefully when referring to animals. “It’s not surprising that speciesism shows up in language,” says language teacher and vegetarian activist Dr. George Jacobs. “But if we can change language, maybe we can change views.”

Keim’s editors at Nautilus were “totally on board” with his he-and-she pigeons, he says. But this isn’t always true. In the early 1960s, Jane Goodall turned in her first paper about the chimpanzees of Gombe, only to have it returned to her with official instructions that each he, she, and who referring to a chimp be replaced with it or which. (“Incensed, I, in my turn, crossed out the its and whichs and scrawled back the original pronouns,” she writes in her memoir Through a Window).

Nearly half a century later, inspired by Goodall’s experiences, Jacobs collaborated with linguist Gaëtanelle Gilquin on a broad-scale study of animal pronoun usage, surveying style guides for relevant rules and combing a large corpus of English literature for examples.

Moby-Dick, a definite “he.” (Image: A. Burnham Shute/Public Domain)

Gilquin and Jacobs found written and spoken English to be fairly hospitable to individuated animals—“dogs who wander,” “alligators who wrestle,” and “catfish who love to be fed by hand” all showed up in the corpus. Literature also has its share: Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar features “a lion who glared” at Caesar’s assassins, and Moby-Dick is always a “he.” Pets, like Socks Clinton, invariably got the humanoid pronoun treatment.

When it came to official directives, things were a little less clear-cut. Plenty of style gurus, from the Chicago Manual to the American Psychological Society, forbid the use of humanoid pronouns to refer to animals. The Oxford English Dictionary will allow “who” to be used for an animal “with implication of personality.”

Most newspapers afford animals personal pronouns as long as they’ve already got another human accoutrement, like a name or a gender designation. According to the current New York Times Style Guide, if Marmaduke is lost, one should write “he howled,” but if a nameless dog is lost, said howler becomes it. The Washington Post has the same strategy, with a contingency plan: “I could see exceptions for descriptions of wild-animal mating or mothering, where the sex is integral to the point and gendered pronouns would aid comprehension,” wrote copy editor Bill Walsh in an email.

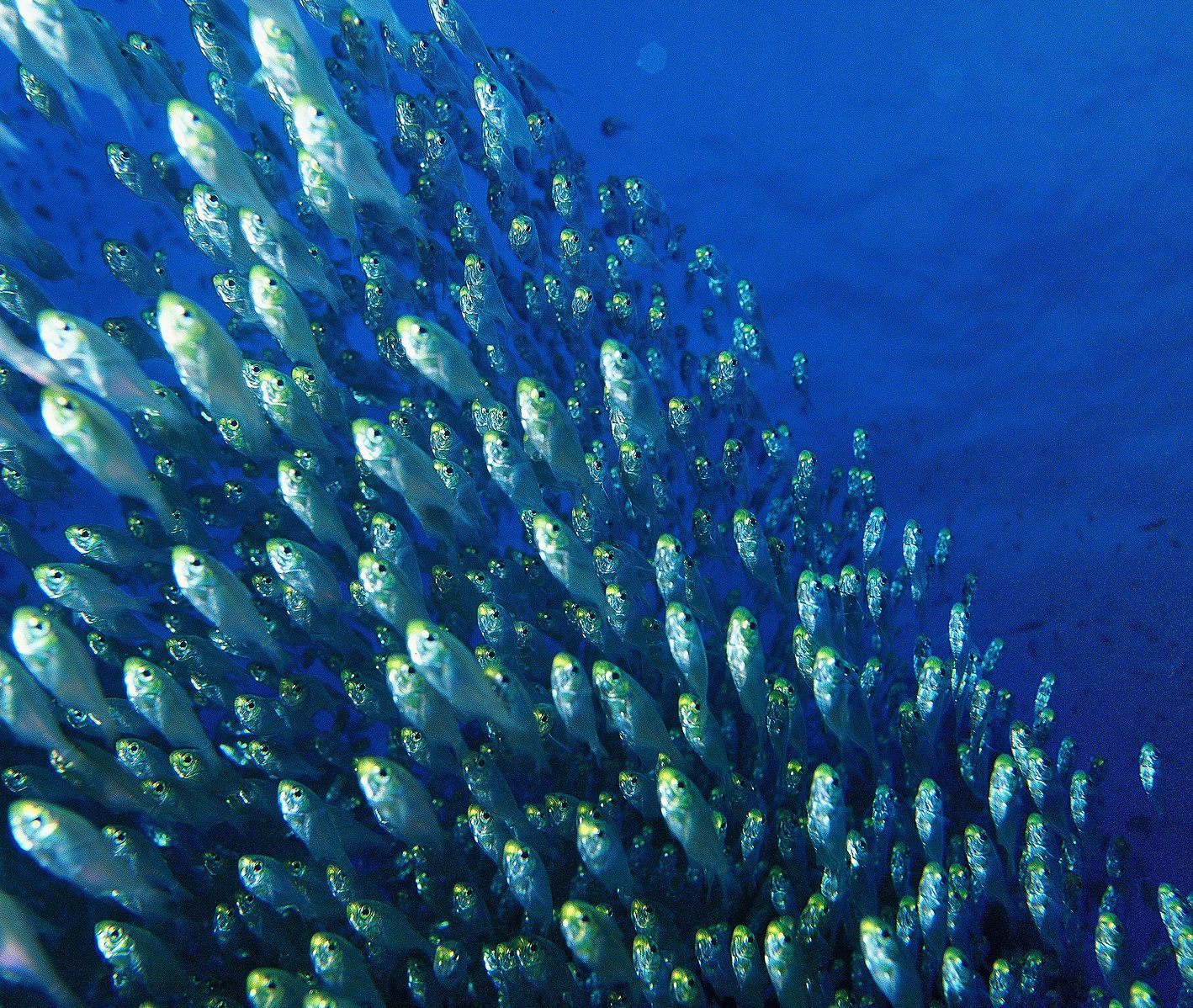

Are these fish individual enough to get their own pronouns? (Photo: WikiCommons/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Such looseness does not sit well with Carl Safina, a wildlife biologist and scientific communicator who developed a clear set of animal pronoun criteria while writing Beyond Words, a book about wildlife intelligence. According to Safina, “who” should be used for any individual “who has a relationship to other individuals,” regardless of species. Under this umbrella, elephants and bears are “he,” “she,” or “who,” while mosquitos and fish are not.

For Safina, this division stops up a potential cascade of anthropomorphized living things, and denotes a real and important distinction. “A herring in a school of herring, where there’s no structure, there are no bonds, there’s just a grouping—it doesn’t bother me to refer to them as it,” Safina says. On the other hand, if someone makes a good case for herring-as-whom, he’s open to it. Keim draws his line a little further along in the sand. “I’ll still use who, even for earthworms,” he says. (Microbes and plants, though, are its for him—though some, like botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, have argued for personal plant pronouns, too.)

Cow Who Escaped New York Slaughterhouse Finds Sanctuary https://t.co/ld1gm2erQN via @nytvideo

— Gena Hamshaw (@thefullhelping) February 24, 2016

Lately, a little bit of this ethos has started creeping past the grammatical gatekeepers. Last month in the Globe and Mail, Peter Singer pointed out that, against their purported style, the New York Times headlined a story on a runaway steer “Cow Who Escaped New York Slaughterhouse Finds Sanctuary.” Perhaps the cow’s dash at life made him more relatable, more agential—or maybe, Times standards editor Philip Corbett mused, headline writers were justified by his eventually receiving a name (he is now Freddie). Regardless, the switch didn’t last long—in its first sentence, the article reverted back to “that.”

Keim hopes that, next time, the Gray Lady will consider granting who to the cow more permanently, along with its wild and domestic brethren—fuzzy and slimy, large and small. “Goodall broke through the barrier with chimpanzees,” he says, “and now I think that consideration should be extended to everything else.” He corrects himself: “Everyone else.”

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to cara@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook