Why New York City Has a Public Bathroom Problem

Decommissioned bathroom in Wall Street subway stop in NYC. (Photo: Daniel Schwen/Wikimedia Commons)

The NYPD issues between 20,000 and 30,000 citations for public urination each year. But while there may be victims of that crime (mostly, sides of buildings and passersby), it’s not clear who really is at fault—the person who is relieving him or herself, or the city.

Public urination, which may soon be reduced from a misdemeanor to a more minor violation, is a response to a significant infrastructure in New York and most other major cities. And unlike other infrastructure issues—bike lanes, say, or graffiti—the problem that results in public urination has proved ridiculously intractable. It is one of the hardest urban problems to fight.

“Public toilets are as essential a part of street infrastructure as streetlights,” says Carol McCreary of PHLUSH (“Public Hygiene Lets Us Stay Human). “They need to be part of the same package, and the fact that they’re not makes no sense.” New York City, just to take an example, offers public bathrooms in some parks (around 700 of the 1,700 total parks in the city) and a couple in scattered subway stations, both of which are often closed. And there are three pay toilets, one in Manhattan, one in Brooklyn, and one in Queens. Compare that to Singapore, which has fewer inhabitants and over 30,000 public bathrooms.

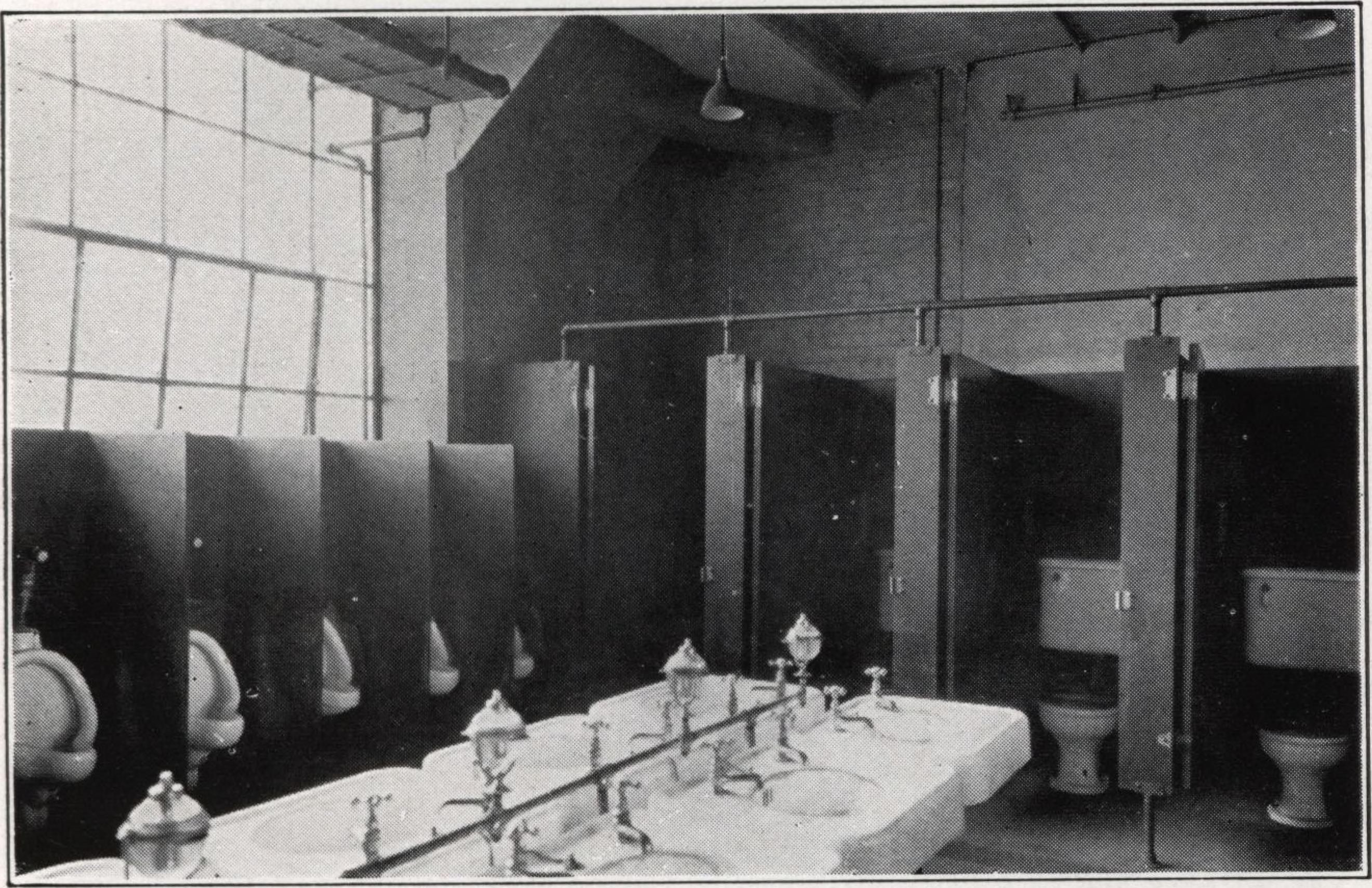

A public bathroom built in Philadelphia, in 1922. (Photo: Public domain)

Public bathrooms have a long history, dating back to the bathhouses of the Romans, but the first major urban centers to offer a public bathroom program were Berlin and London, in the mid-19th century (you can read more about that in Der Spiegel, if you can understand German). New York City, though, never adopted this trend. By the turn of the century, New Yorkers were complaining about the total lack of public toilets with no optimism for a solution whatsoever. Suggestions for public restrooms were made by as important a group as the Committee of Seventy, the Samuel J. Tilden-led anti-corruption group. “Probably the most flagrant failure in American sanitation today is the almost universal lack of public convenience or comfort stations in American cities and towns. Failure like this to provide proper public toilet facilities is to fail in one of the very elements of sound public health,” pled MIT doctor William T. Sedgwick to the New York governor in 1915.

They got nowhere.

Elsewhere, bathroom facilities sprung up. Eisenhower’s highway program in 1956 included resources for creating rest stops along the brand-new interstate highways—a crazy idea, at the time. But soon enough, travelers were able to find bathrooms while on the road. At first, those bathrooms were all pay toilets, only able to be unlocked with a dime, but four high school buddies (seriously) created a campaign that eventually ended the reign of the pay toilet in around 1976. After enough lawsuits and public outrage, facility after facility was unlocked.

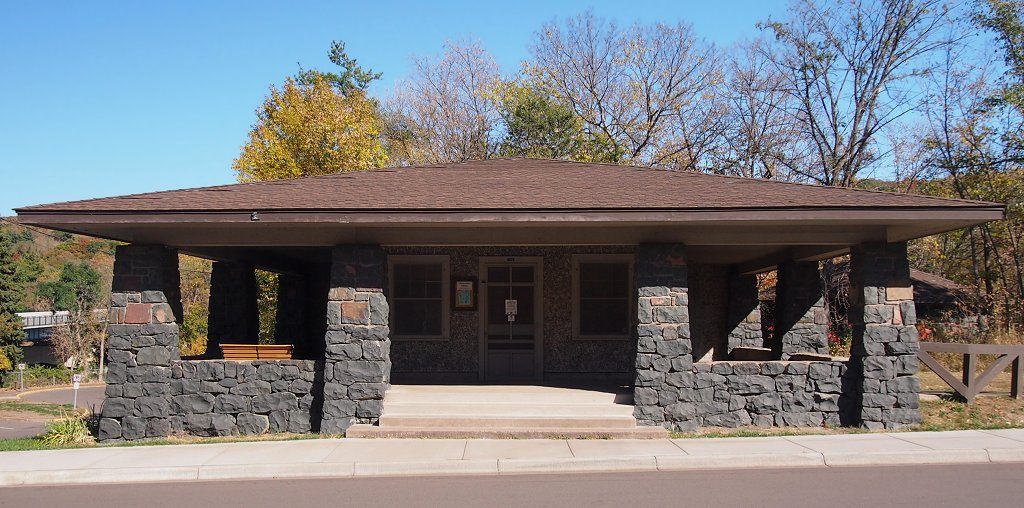

Rest stops changed the travel game in U.S. (Photo: McGhiever/Wikimedia Commons)

Though it was great that the public bathrooms became free, it had undesirable side effects as well. Restrooms came to be seen as a horrible money pit, an expensive facility that brings in no money but which costs huge amounts of money to clean. Architects and city planners crafted the bare minimum of public bathrooms required by the law, which was often none at all. (Office buildings and hotels have minimum bathroom requirements, but are not really public.) And the company that made the locks for the public bathrooms before those high school kids shut them down conducted a huge marketing campaign in which they promised that free public bathrooms would be home to all sorts of unwanted people and unwanted acts by those unwanted people: drug use, vandalism, minorities, public sex, maybe even gay sex, who knows? Those perceptions stayed for decades after, and in part persist today. These perceptions are not completely untrue, but they’ve been used as an excuse to stop even trying to create a decent bathroom infrastructure.

The people who build our cities became enemies of the public bathroom. They remain so, but they have enemies themselves.

In fact, the activist groups desperately trying to get public bathrooms in American cities never really went away. PHLUSH, McCreary’s group, is one of a small handful of groups fighting upstream, like a salmon trapped in a river of urine, to get public restrooms installed in cities. Their reasoning is multipronged. For one thing, adding public bathrooms is linked with revitalization (or gentrification, depending on how you look at it) of distressed neighborhoods. It’s kind of the same idea as attacking litter or graffiti, which is strongly correlated with decreases in other types of crime.

A Colorado public bathroom. (Photo: Bradley Gordon/Flickr)

Urine is not a fantastically dangerous substance, gross though it might be. It’s alleged to have corroded a pole in San Francisco, and theoretically holding it in for a long period of time can be dangerous, but for the most part, the objections to public urination are more aesthetic. It smells, for example. But the main reasons to institute a public bathroom system in a city is simply because we should. “It’s a fundamental human right,” writes Safe2Pee, another activist organization. It is a need shared by all people, and to not provide bathrooms while making public urination illegal is kind of ridiculous.

Yet it’s proved incredibly difficult to get any traction in the effort in many cities, New York included. The main reason is that it’s a costly and difficult project. Cities like Portland, where PHLUSH is based, have a low enough density that it’s possible to construct sidewalk public bathrooms. (The Portland Loo, a metal pod placed on the sidewalk, has been a success there and elsewhere.) But in New York, the density of people on sidewalks is much too high to stick a public restroom every four blocks. “Restrooms are expensive, even modular units placed in parking lots,” says McCreary. The Portland Loo costs about $60,000 each to construct, and another $1,200 a month to maintain. To install a few thousand of these around New York could veer into the tens of millions of dollars just to install.

But, depressingly enough, that’s not even the biggest problem. At least, not the most frustrating one. “The peepee caca jokes are…we usually warn people, you’re gonna get six months of jokes and funny headlines from the press,” says McCreary. “And television journalists are the WORST.” Any mention of spending on toilets meets with horrible, cheesy jokes and a weird belief that this is not a real problem, or not worth bothering with. “I think why it’s hard is that we don’t talk about it. It’s really hard to push it on the policy agenda,” says McCreary.

But we’re at a strange tipping point right now. Bathrooms are in the public eye more than ever, thanks to the battle over gendered bathrooms specifically as they apply to transgendered people. Starbucks, long considered New York City’s unofficial public bathroom operator, has basically stopped allowing people to use their bathrooms. The city’s new relaxation of the laws banning public urination may be sensible, but they don’t answer these age-old problems: where does a New Yorker go to pee?

Bathrooms in the Church Street station in NYC. (Photo: Sam Sebeskzal/Wikimedia Commons)

Some private sources are stepping up to answer that question. AirPnP, a punny and apparently buggy app, allows users to put their bathrooms up for rent. Posh Stow & Go is sort of like a locker room infrastructure, with locations offering locker storage and bathrooms. But these apps are as yet unreliable, and even at peak density don’t come anywhere near the amount of bathrooms a city like New York should have. Both federal law and New York plumbing code demand a minimum number of bathrooms based on the number of employees or visitors to a business, but make no requirement that those be made available to the public—so business have, almost invariably, chosen to keep them for customers or employees only. The war for the people’s toilets continues.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook