Why Massive Radio Telescopes Might Be Our Best Shot at Finding Aliens

The search for extraterrestrial life is amping up, after China’s debut of the world’s largest radio telescope.

China just built the world’s largest telescope to hunt for E.T. https://t.co/GhqhwqFD9W pic.twitter.com/9Km6POjaJf

— Popular Mechanics (@PopMech) July 6, 2016

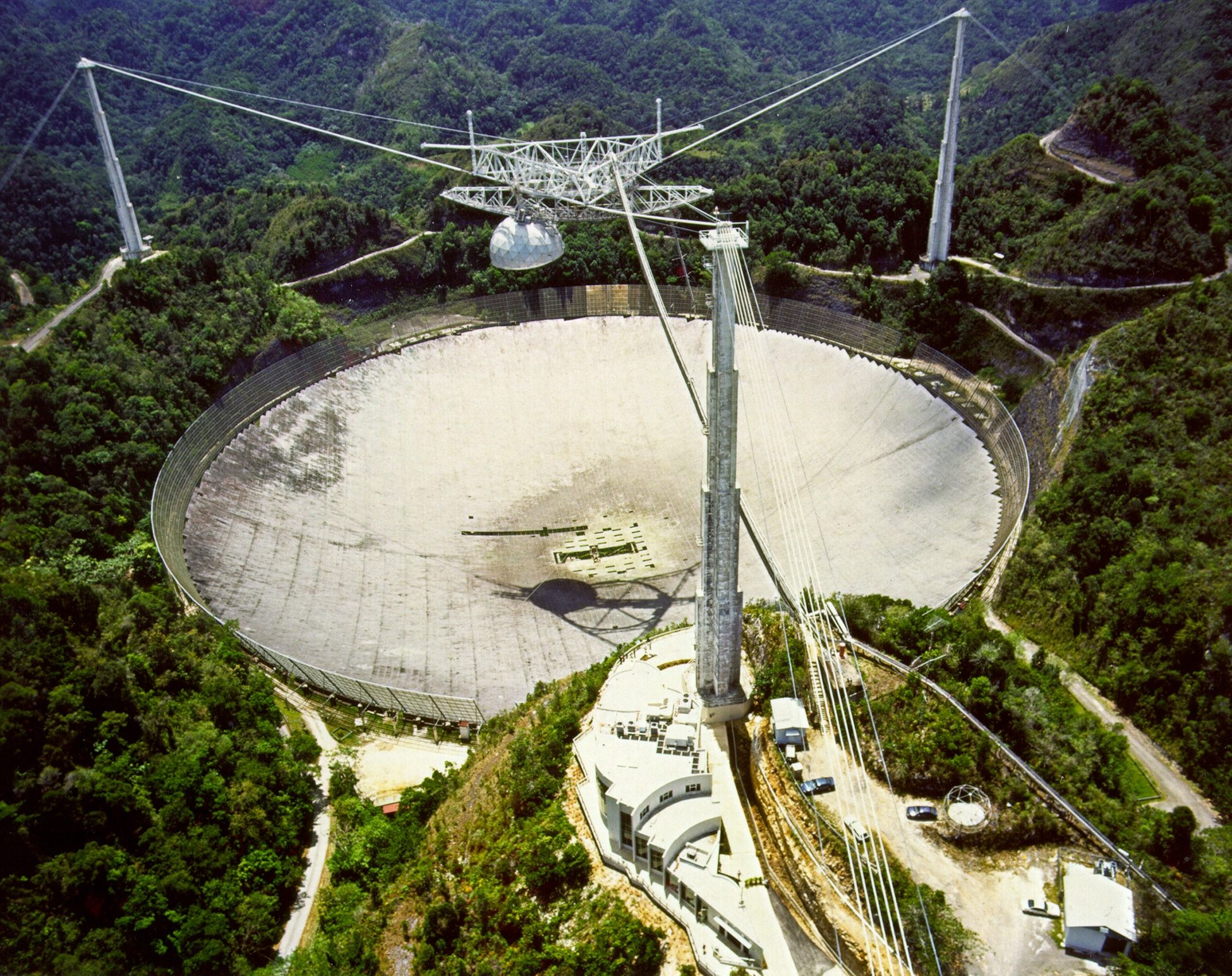

In the movie Contact, a fictional astronomer played by Jodie Foster is seen, in the beginning, at the 305-meter-wide Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, which was, until this week, the world’s largest radio telescope.

What was Foster looking for? Intelligent life, of course, which, in the movie at least, she later (probably) finds while working at a different complex of radio telescopes, the famous Very Large Array in New Mexico.

This is Hollywood, of course, where facts are sometimes hard to come by, but the movie, based on a book by Carl Sagan, still presents a scenario that many scientists consider our best chance to actually discover intelligent life: through radio signals.

That’s because some radio signals, which can be easily detected by such telescopes, do not appear in nature, meaning that if we ever detected them, they would likely be coming from a being capable of producing technology.

And the search for these signals has been going on for awhile, of course. The Arecibo has been in operation for 53 years, and most of that time has been spent looking. (With SETI@home, you too can join in.)

But this week, the Arecibo got a new competitor—or at least a new companion—in the search for intelligent life: A 500-meter-wide radio telescope in China’s Guizhou province, which has now become the world’s largest such telescope.

The telescope, officially called the Five hundred meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, will begin operating in September, and China has said that they hope to open its abilities to scientists across the world in three years.

The new telescope wasn’t much of a secret—earlier this year, it emerged that China was working on it—but its scale was breathtaking, even for some scientists.

It cost $185 million, for one thing, and included 4,450 triangular panels, which comprise the telescope’s massive bowl. When operational, it will be able to listen to up to 1,000 light-years in the distance.

FAST will also be 10 times as sensitive as the Arecibo, meaning that not only will it be able to detect signals that have come in from farther out, it will also be able to detect finer frequencies.

The search for aliens, in other words, is getting serious.

Radio telescopes are not like optical telescopes, the sorts of telescopes you might have grown up with, perhaps trying to spy on the moons of Jupiter.

Radio telescopes don’t detect anything visually, instead listening to radio waves in the universe, which occur for all sorts of reasons. A lot of them come from stars like the Sun, which emits a constant stream of radio waves, which are also a type of radiation.

But some radio waves simply don’t occur in nature, and its these that scientists hope to one day capture with radio telescopes.

It’s a search that China might be starting in earnest now, but that the Arecibo has undertaken for decades. And if the Arecibo’s record is any indication, FAST will have quite the history to live up to.

One of the telescope’s first discoveries, for example, was that Mercury rotates on its axis every 59 days, shorter than previously thought, a discovery made in 1964, just months after the telescope opened. Twenty-six years later, it found the first planets ever to be discovered orbiting a star other than the Sun. And, in 1999, it launched SETI@home, which lets amateurs search for intelligent life using their home computers.

We haven’t found it yet, of course, though SETI@home has detected some odd radio signals over the years, like one 1420 MHz signal detected in 2003 that still hasn’t been adequately explained. But it’s probably nothing: scientists have said that it came from a part of the universe where no stars were known to exist within 1,000 light-years. It was also very weak. (The headline of an article announcing the find, published in New Scientist in 2004, offered an intriguing, if ultimately disappointing promise: “Mysterious signals from light years away.”)

And, in fact, the Arecibo hasn’t only been used to try and listen to alien life; it’s also been used to try to communicate with it. Take 1974’s so-called Arecibo Message, written by the scientists Carl Sagan and Frank Drake, which was sent to a cluster 25,000 light-years from Earth.

Puerto Rico’s Arecibo Observatory, the previous record holder in terms of size, at around 305 meters wide. (Photo: Public Domain)

The message was largely a publicity stunt, created in part to show just how powerful the telescope is. And since it was sent 25,000 light-years away, any response would take just as long to get back to Earth, or around 50,000 years, when humans may well be toast.

But, still, it was an effort to initiate contact. And if aliens actually receive and decode the message they’d find just enough information to come up with a response. The message contained a small amount of binary data, or around 210 bytes total, which, when decoded, would produce the numbers 1-10, the figures of a man and woman, a depiction of our solar system, and, most importantly, an indication of which rock closest to the Sun the message had come from.

So, it’s projects like these from which FAST might take inspiration. We may sooner discover alien life in the form of something like a pocket of bacteria, but, for many scientists, the real news will be when we discover what’s commonly defined as extraterrestrial intelligent life: life that’s able to create technology capable of decoding radio signals, perhaps. Or at least hearing them.

Technology, in other words, like what humans have been able to make.

And the scale of that technology keeps getting bigger. Around 9,000 people were evicted for China’s new telescope, for example, as they cleared a 3.1-mile radius around it, so that there would be as little electromagnetic interference as possible. To further reduce interference, it was built in a karst depression, or a depression in the Earth formed when underlying bedrock dissolves. (Karst depressions are also sometimes responsible for sinkholes.)

All of this was designed to find aliens, and, to be fair, also locate some less exciting objects like pulsars. After becoming operational, Chinese officials said that monitoring the radio-wave universe from FAST would now begin for real.

“We have found more than 2,500 pulsars,” You Youling, an astronomer the National Astronomical Observatories, told the state-controlled CCTV. “We hope we can find at least double that number with this gigantic radio telescope.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook