Why It’s So Hard to Find, Let Alone Save, the World’s Cutest Porpoise

The tiny mammal is facing imminent extinction after only being discovered in 1987.

The elusive vaquita. (Photo: Paula Olson/NOAA/Public Domain)

How rare is the world’s smallest (and cutest) porpoise?

“There’s a lot of fishermen that think they’re mythical,” says Barbara Taylor, a scientist for NOAA who’s spent decades on the forefront of vaquita conservation.

The fishermen can be forgiven for thinking the vaquita—Spanish for “little cow”—is some sort of sea unicorn. A recent study indicated that its population is shockingly low, with about 60 left in the world and none in captivity. The scientists involved in vaquita conservation are racing against time, battling gigantic forces of illegal trade and the poverty of fishing villages, along with the governments of both Mexico and China. There does not seem to be much time left.

This is especially sad because we were just getting to know the vaquita. “On a spring day in 1950 Kenneth Norris saw a whitened skull protruding from the sand near Punta San Felipe in Baja California, Mexico,” writes Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, the chairman of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA), in an email. Eight years later, Norris published a paper describing the vaquita. At this point, nobody had ever actually seen one, like, swimming around. Nobody knew how big the vaquita was, how it was colored, what it ate, how it bred, where it lived.

It wasn’t until 1987 that anyone laid eyes on one—and in what would become a disastrous refrain for the vaquita, the first vaquita to ever be seen was dead, killed accidentally in a fishing net.

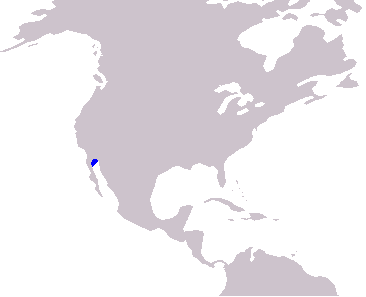

A map showing the range of a vaquita - the northern reaches of the Gulf of California. (Photo: Pcb21/CC BY-SA 3.0)

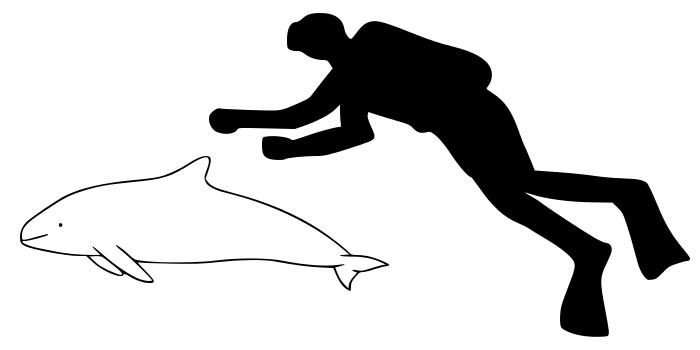

Upon examination, scientists confirmed that it was smallest cetacean in the world, putting it in the same family as dolphins, porpoises, and baleen whales like the blue whale—except that it’s adorably tiny. At about 55 inches long and around 120 pounds, the vaquita is the size of a large dog. Think about that for a second: This is a porpoise the size of an Irish wolfhound. Its coloring looks weirdly like a panda in dolphin form: pale grey and white with dark circles around its eyes and a dark outline around its mouth. It is, without a doubt, one of the cutest animals in the world, but unlike the panda, it’s never managed to become a figurehead for any national or international conservation efforts.

Largely that’s because it’s not only exceedingly rare, but also incredibly shy, fast, and elusive. To this date, a vaquita has never been caught and tagged; Taylor is not entirely sure that can even be done. It lives exclusively in the northern reaches of the Gulf of California, the long inlet in between Baja California and mainland Mexico that’s sometimes known as the Sea of Cortez. It’s a singularly horrible place to study animals, thanks to overactive weather systems and cloudy water.

A vaquita. Note the dark circles around its eyes. (Photo: Paul Olson/NOAA/Public Domain)

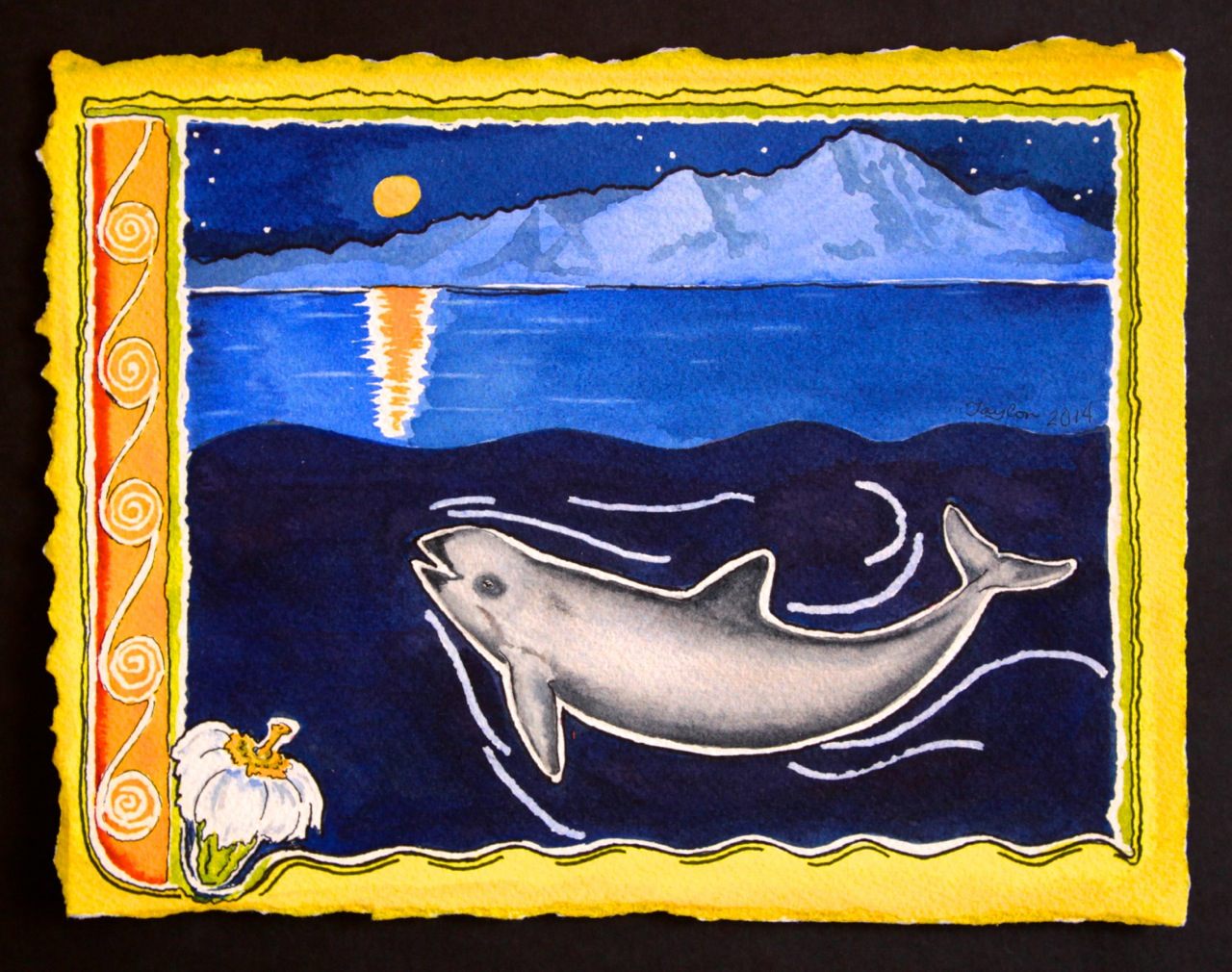

To even see a vaquita in the wild, Taylor goes out on boats equipped with gigantic high-powered binoculars. Vaquitas don’t breach, or jump out of the water into the air, like some dolphins do, instead making short trips to the water’s surface to breathe before heading back down. “It’s been a source of frustration, because places like National Geographic, in their main magazine or on TV, don’t want to cover the vaquita because they can’t get full-frame pictures of the animal in the wild underwater,” says Taylor. “And that’s just never going to happen with this species.” Because getting good pictures of the vaquita is so difficult, Taylor has actually started painting it, mostly in gentle watercolors that sometimes depict the vaquita frolicking with animals that do not technically live in the Gulf of California, like the panda.

What the vaquita is even doing in the Gulf of California is up for debate. “It’s a very unusual place to even find a porpoise,” says Taylor. “Usually porpoises live in colder, productive waters.” Mitochondrial testing indicates that its closest relative is the Burmeister’s porpoise, another small porpoise found, in its northernmost range, thousands of miles away, off the coast of Peru. “The hypothesis is that a group of the Burmeister’s porpoise, or a related form, was at the end of an ice age trapped in the Upper Gulf giving rise to a population restricted in numbers and range,” writes Rojas-Bracho. It’s thought that the vaquita, even before the insane drop in its population over the past decade, was always a rather rare animal; it’s unlikely that there were ever more than a few thousand of them. Taylor jokes that they all have “the same last name,” but inbreeding, until the recent drop in population, was not really a problem, as they’ve been a stable presence in the Gulf for about three million years.

A pair of vaquita. (Photo: Paula Olson/NOAA/Public Domain)

Part of what makes the vaquita’s plight so frustrating is how simple it is: unlike most animals whose populations are declining, the vaquita’s demise is due to exactly one factor. Human development? Not a problem for the vaquita. Pollution? Well, the Gulf of California is actually pretty pristine, as far as that goes, and analysis of the vaquita’s blubber showed that it’s not only not at risk from pollution. “They actually have the cleanest blubber of any marine mammal on the planet,” says Taylor. It eats basically anything that it can catch, and there’s a lot of food in its area.

The problem is gillnets, large vertical strips of netting that capture gigantic quantities of anything that swims into them. In the past, gillnets aimed at the shrimp harvest were a problem for the vaquita, reducing the porpoise’s numbers by about 8 percent per year. That’s a horrible number, would be dangerous for any species, but it’s not why the vaquita is down to 60 today.

A vaquita size comparison - they measure approximately 55 inches long. (Photo: Chris_huh /CC BY-SA 3.0)

The real target of the nets is the totoaba, a bony croaker-like fish that’s caught for its swim bladder. The swim bladder is prized (the bladders can fetch as much as $18,000 each on the black market) as a delicacy, a skin treatment, and a fertility treatment in Chinese medicine. Fishing for the totoaba is illegal in all countries, and after pressure from groups like CIRVA, the Mexican government enacted a two-year ban on gillnet fishing. But when a single fish can net you a brand-new Honda Civic, you’d better be sure the penalties for getting caught are severe.

Unfortunately, Taylor says the penalties are roughly as much as the selling price of one or two swim bladders. The only way to even get hit with a penalty is to physically get caught fishing for totoaba with a gillnet, and with hundreds of fishing boats in the Gulf and just a handful of patrol boats, the odds are in the poachers’ favor. That’s further made worse by a loophole in the Mexican ban: Gillnet fishing for another species, corvina, is legal.

The situation with totoaba fishing is not entirely unlike drug smuggling in that there must be efforts on both the producer and the consumer side to reduce the trade. Unfortunately China has made few steps towards actually reducing demand for the product, one sometimes referred to as “aquatic cocaine.” And as long as the swim bladder is insanely valuable, and the penalties for getting caught so minimal, the totoaba will keep being fished with gillnets, and the vaquita will keep getting caught in them.

One of Barbara Taylor’s vaquita artworks. (Photo: Courtesy Barbara Taylor)

For some animals, like the black-footed ferret and the California condor, captive breeding has been used as a last-ditch attempt to save the species. (The few remaining animals are caught, bred in captivity to increase their numbers, and then released back into the wild.) The same tactic has been considered for the vaquita but, well, nobody really seems optimistic about it. For one thing, it’s up in the air if we could even catch a vaquita; nobody’s ever done it before and there’s no real reason to assume we could just go out and snag one. For another thing, it’s never been held in captivity. To capture a vaquita and have it die in captivity would be torturous, and reduce the species’ population even further.

Still, Taylor says she’s “guardedly optimistic” about the species’ survival. Inbreeding is probably less of an issue with the vaquita than with many other animals, because it’s already proved sustainable with a small population. And you’d be surprised at how few individuals you need to bounce a species back: the northern elephant seal, for example, was killed down to about 20 individuals in the late 19th century before being unilaterally protected. Now there are over 100,000 northern elephant seals in the wild.

Organizations like CIRVA and the World Wildlife Fund are campaigning hard, but there are concrete measures that need to be taken. Without a full ban on gillnets and legitimately discouraging fines, the vaquita—one of the best animals on the planet—may have only a few years to live.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook