Why Every Kid in America Learns to Play the Recorder

There’s more to the instrument than “Mary Had A Little Lamb.”

All across America, for decades, a strange cultural ritual has been enacted. Students at the end of elementary school are herded into rooms and handed a simple, hard white plastic instrument called a recorder that seems pathologically incapable of creating any complex music.

Learning to play the mass-produced wind instrument is an integral part of the curriculum of most elementary school music programs in the United States. Screechy, hesitant, clumsy, it’s hard to imagine anyone actually playing the instrument seriously.

But this disposable educational toy is a relatively new chapter in the instrument’s long, storied history. Its journey to U.S. classrooms involves a passionate German composer and a plethora of suddenly cheap plastic. There’s much more to the recorder than butchered renditions of “Mary Had A Little Lamb.”

“The recorder is very old, almost as old as notated western music,” writes John Everingham, the owner of Saunders Recorders, a specialist dealer in recorders in Bristol, England. Instruments that are immediately recognizable as recorders have been discovered dating back at least 700 years. (One particularly famous example is the Tartu recorder, found in an ancient Estonian latrine and dated to the 14th century. An archaeologist actually played it. After cleaning, presumably.)

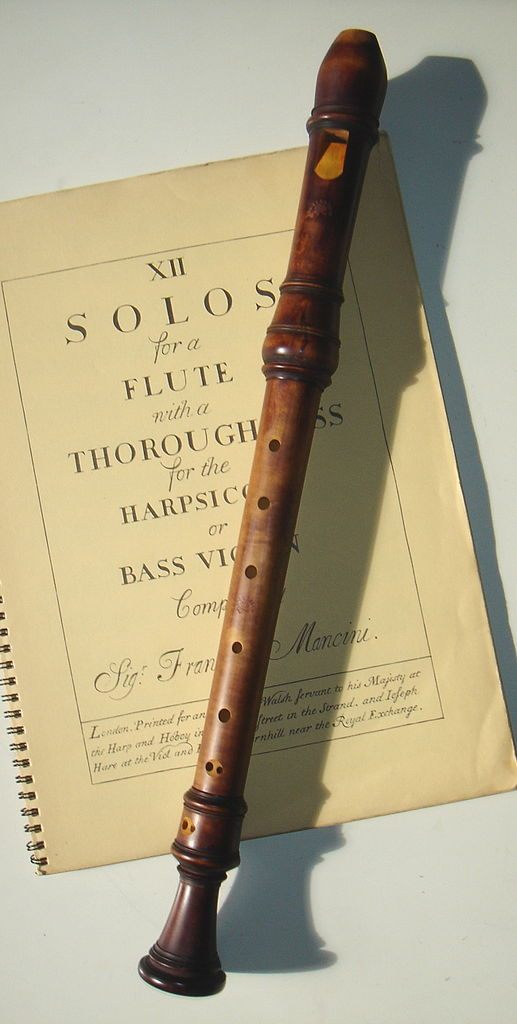

But what really is a recorder? The recorder is a type of flute; in fact, it’s probably the original kind of flute, and technically the flute that we all recognize as a flute, the one that’s played by blowing into the side of the instrument, is called a “transverse flute.” The English name “recorder” is kind of an oddball; in most other languages its name positions it as some sort of flute. It’s flûte à bec in French, meaning “beaked flute” and referring to the shape of the mouthpiece, which sort of looks like a bird’s beak. In German it’s blockflöte, with “block” referring to the part of the recorder that constricts the breath of the player—a block of wood. (In English that block is called a “fipple,” which is a fun-sounding word.) The English name dates from an obsolete meaning of the word, which was more like “practice.”

There are similar flute-type pipes around the world, but the recorder, says Everingham, is generally assumed to be a western European creation. Other flutes, like the Japanese shakuhachi, look much like a recorder but are constructed and played differently. (The shakuhachi is played by blowing air over the surface of the mouthpiece, like a beer bottle.) “The design has changed over the centuries but the distinguishing feature of the recorder is the hole covered by the thumb at the top of the instrument, and a hole for the little finger at the bottom,” says Everingham. Without those bottom holes an instrument would be more accurately described as a whistle.

The recorder is a very direct instrument; unlike most others, the sound comes not from the vibration of any other material (like a string in a guitar or a reed in a saxophone) but from the constriction of the breath. It is, basically, a whistle, and changing the path of the air by covering up holes in the body of the recorder changes the notes. That makes for an easy instrument to play but also a strange one. Because there’s no modulation of the player’s breath, it requires a lot of concentration to keep the tone steady. “If you’re nervous it comes through, laughing it comes through, you have to be pretty focused,” says Susan Burns, the administrative director of the American Recorder Society.

There are many many varieties of recorder; like other woodwinds, it comes in sizes that are roughly pegged to the human vocal range. The recorder that we all learned to play (sort of) as kids is the soprano recorder. The recorder can be as large as the sub-contrabass recorder, which is about eight feet tall and requires a long tube-shaped mouthpiece trailing downwards from the top because no human can actually stand and play it. On the other end of the spectrum is the garklein, a teensy, high-pitched variation. “It’s about six inches long and makes my dog howl every time I play it,” says Burns.

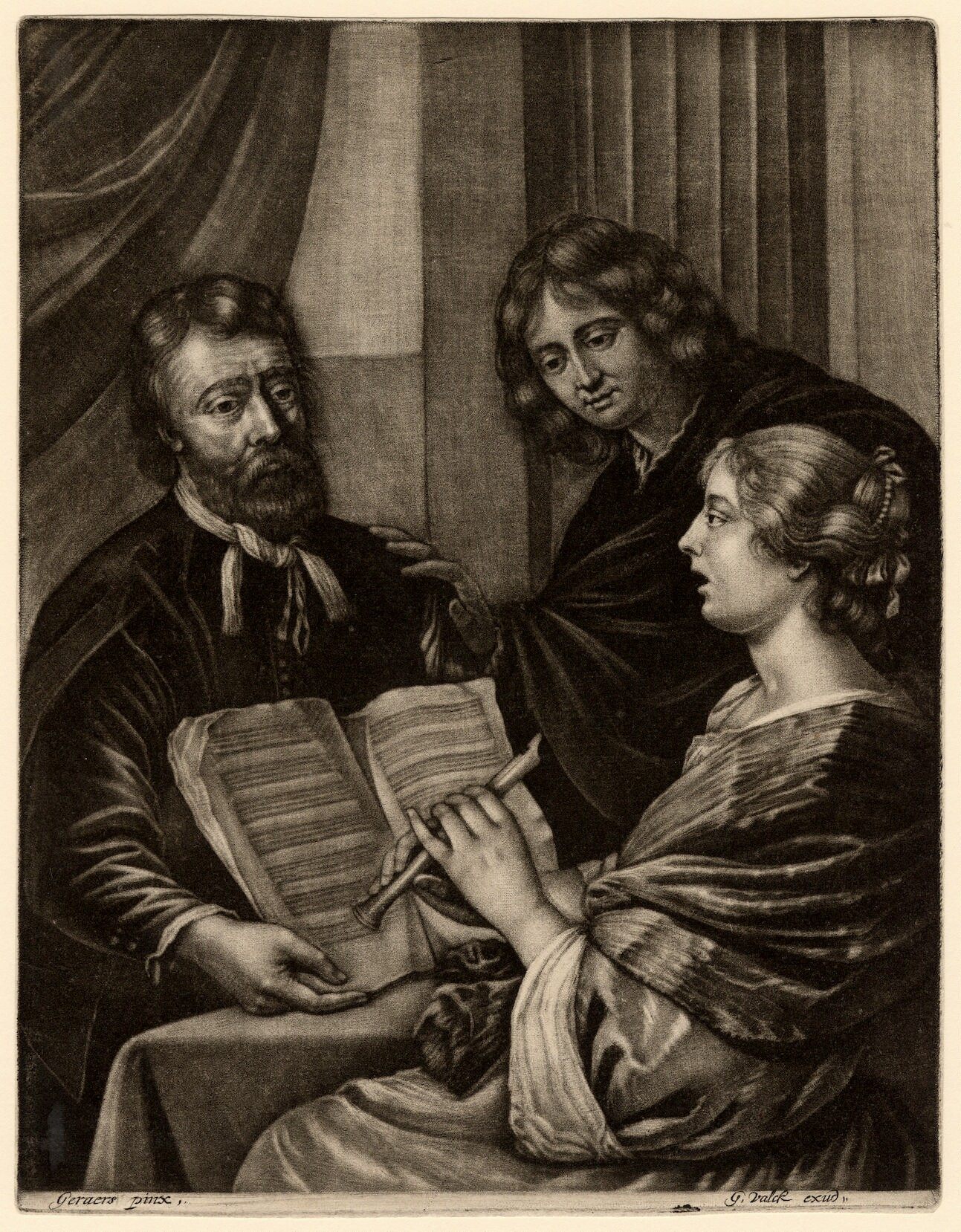

In modern musical culture, the recorder has two very distinct purposes: as a teaching aid and as a revival instrument. “The Baroque era was kind of the golden age of the recorder; Bach wrote many many pieces, Vivaldi, all the big guys,” says Burns. It was not a solo instrument, but usually used with many other recorders of varying sizes. Its heyday was short-lived, though. The transverse flute (which we would recognize today as the “normal flute”) arrived from Asia in the 14th century and steadily supplanted the recorder until it essentially replaced it by the mid-19th century. “You don’t find it too much in a modern orchestra after 1850,” says Burns.

But the instrument was rediscovered in the early 20th century and quickly put to use as a revival instrument. Soon enough its plaintive, childlike tone branched out from there; some rock and pop acts used it (Paul McCartney was a fan, using it in some Beatles songs like “Fool On The Hill” and some of his solo work), and it was also snagged by some more contemporary and even avant-garde composers. It can be very pretty!

But where it’s most recognizable is as a teaching tool. It has a few key advantages in that capacity. For one thing, ever since the 1960s, it’s been manufactured in insanely cheap plastic, which is near-indestructible and can actually sound quite good. “Some of the very cheapest recorders can produce sounds very close to the very best, but at a hundredth of the price,” says Everingham. It’s an accessible instrument. Unlike, say, a saxophone, or even a guitar, no real technique is needed to actually make sound come out. You simply blow, which gives young students a big step up in the learning of the recorder. And the soprano recorder is a perfect size for a small child’s hand, so there’s no need to make a smaller version for younger players.

The soprano recorder came into being as a teaching tool in the early to mid-20th century thanks to the efforts of one Carl Orff, a sort of revivalist German composer. He’s best known as the creator of Carmina Burana, the name of which may not ring a bell but which we can absolutely guarantee you have all heard, most likely in the trailer of an action movie.

Aside from his compositions, Orff was perhaps the most influential and important architect of music education theory in the 20th century. His Orff Schulwerk was an approach to teaching music that relied on rhythm and creative thinking above rote memorization. It also called for an array of simpler instruments, largely those that mimicked the vocal range of a child. The rationale: if a child can sing it, he or she is more likely to understand it. The instruments should also be inexpensive, simple to understand, and easily stored. That’s where the soprano recorder comes in, along with other common teaching instruments like the glockenspiel.

As for manufacturers, many stepped up with the proliferation of advanced plastic work to create incredibly low-cost versions. No one company really pioneered the plastic recorder; Yamaha, Zen-On, and Aulos occupy the higher-end plastic recorder market, but mostly, those are not the models used for schools. Even a $5.00 recorder can be too expensive when multiplied by hundreds or thousands of students. Instead, low-cost makers like Lyons sell fairly decent plastic recorders for around a dollar each—and they’ll go cheaper if you buy in bulk.

Not everyone is thrilled that the recorder is most often associated with elementary school. “[I] tend to the view that the recorder is not so very suitable for children to play in their formative years. Indeed its use in schools throughout the world have made it more an instrument of torture than an instrument of music, and it must have turned generations off music-making for the rest of their lives,” writes Nicholas Lander, the proprietor of the very useful Recorder Homepage site, in an email.

Even Susan Burns, who in our phone conversation showed nothing but gleeful joy in talking about the recorder, defended it from this characterization: “It is a professional instrument in its own right. Everyone says, oh, it’s so easy to play, but it takes a lifetime to master.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook