In Early Maps of Virginia, West Was at the Top

But why?

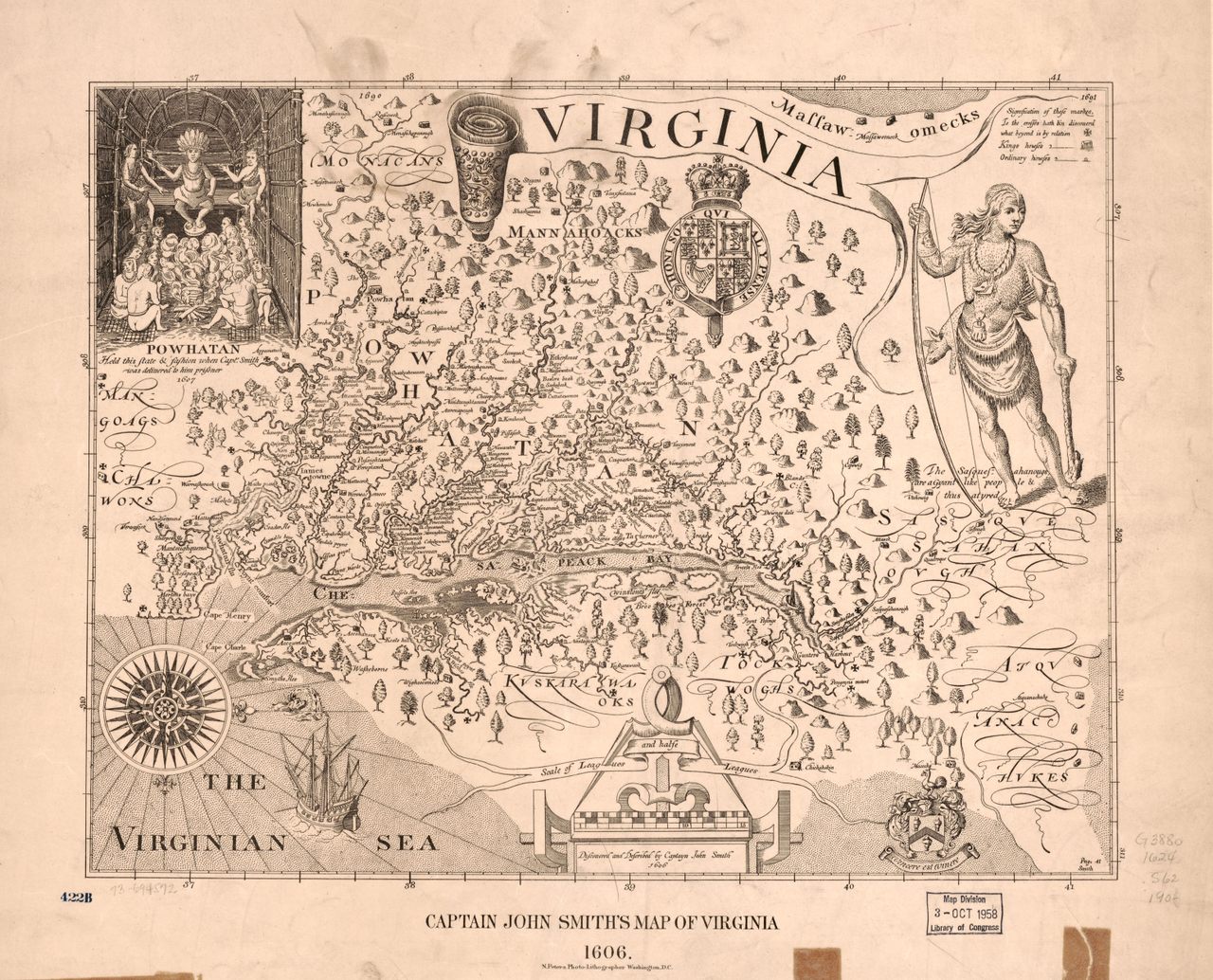

Captain John Smith is perhaps best known for his (possibly fictional) encounter with Pocahontas. Whatever the true nature of that meeting was, the British explorer distilled his explorations and meetings with the indigenous people of what is now Virginia into a remarkable map that defined European impressions of the region for the majority of the 1600s.

Widely considered a masterpiece, Smith’s map is dominated by artistic renditions of the indigenous people of the region, especially Powhatan, the powerful leader of at least 30 Algonquin-speaking tribes in the Chesapeake Bay area, including the Potomac, the Chesapeake, the Mattaponi, and the Secacawoni. On Smith’s map, Powhatan is the name of a man, a region, and the river that European settlers would rename the James.

If Smith’s Virginia looks unfamiliar to the modern viewer, it’s not only due to the extensive territory held by indigenous people. Smith drew his map with west at the top and north pointing to the right, spreading the land out the way it might have appeared to a European ship captain landing on the mid-Atlantic coast.

Orienting maps toward the west this way has always been rare. Though mapmaking conventions, such as standard orientation and use of latitude and longitude, still hadn’t fully formed by the early 17th century when Smith’s map was published, maps showing north at the top were already common. According to Matthew Edney, a professor of geography and cartography at the University of Southern Maine, by 1600, most regional and commercially produced maps were oriented toward the north.

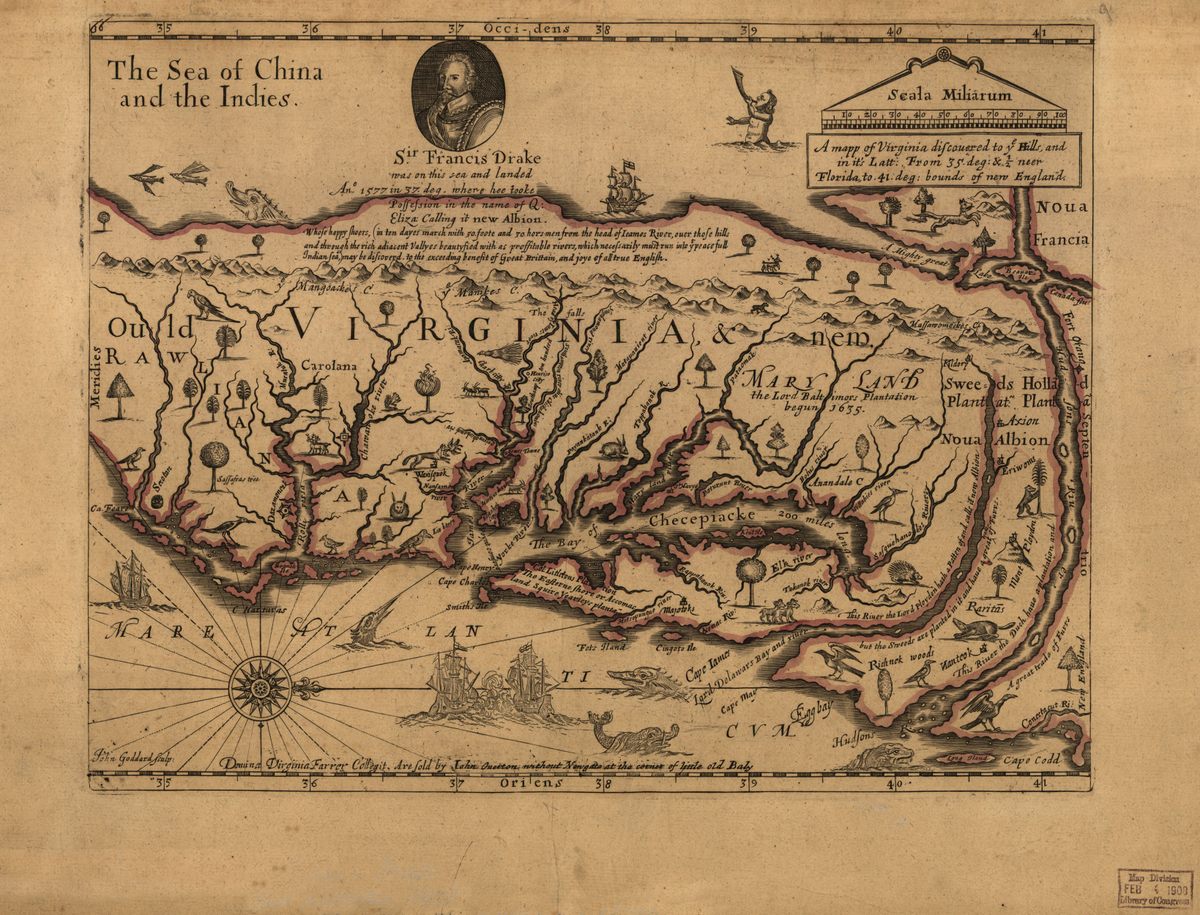

However, many Virginia maps of the 17th century mirror the orientation of Smith’s. These include Augustine Herrman’s Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670; John Lederer’s A map of the whole territory traversed by John Lederer in his three marches; and John Ferrar’s A map of Virginia discovered to ye falls. Some scholars see meaning in the decision to draw these maps with west at the top. The viewpoint of the map, after all, could reveal something about the viewpoint of the mind.

“Maybe it’s about an invitation more than a geography lesson,” says Buck Woodard, a lecturer in the department of anthropology at American University. He notes that many maps of the era were used in part to encourage Europeans to travel to North America as settlers.

Woodard points out that British explorers of the time also drew maps of Ireland with west at the top. In both cases, the British were in the process of conquering territory and establishing settlements. “When there’s a colonial interest, the map is oriented for your arrival,” he says.

But this isn’t the only theory about the unusual orientation of this set of maps. Edney wonders if the orientation toward the west is geared in part toward the European explorers’ desire to establish an easy sea route to China. The maps’ viewpoint could be a way of looking past this land and toward the sea they hoped to discover just beyond.

Or it’s possible that the maps are oriented to make the most of the cartographers’ knowledge, Edney says. European explorers did not know what lay beyond a certain westward point, or knew only what they had heard from indigenous people.

Edney notes that, when maps of Virginia place west at the top, they show a thin strip of land that stops at a barrier. That barrier could be geographic, such as the Blue Ridge mountains, or it could be the nations of indigenous people.

The presence of indigenous people did confine early European explorers within a certain region during their early experience of the territory. Audrey Horning, a professor of anthropology at William and Mary, says this could have influenced the way Europeans drew their maps. “What is especially striking about a map such as John Smith’s map of Virginia is that actually it is a map of the extents of the Powhatan chiefdom,” she says.

On the other hand, there could be merely practical reasons for Smith’s orientation decision. Smith, for his part, may have wanted to arrange the map to work well with wider paper, or he may have wanted to make room for tall illustrations of Powhatan and other indigenous people. Mark Monmonier, a professor of geography at Syracuse University, notes that the group of west-oriented maps of Virginia that followed could simply have come about because people copied Smith, whose map was early and famous.

As the borders of European expansion moved west, the nature of the maps of Virginia also changed. Edney says that it wasn’t until about the 1680s that the colonies along the East Coast of the United States began to be seen as a concrete whole. Around the same time, maps of the area began to be oriented toward the north. He wonders if there’s a connection between the changes and says it’s possible that the north orientation reflected a shift of seeing the region less as a wild area to be traversed quickly and more as a group of settled political entities.

A map by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, called A Map of the Inhabited Part of Virginia containing the whole Province of Maryland, with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina, was published in 1753, and took a role in the 18th century similar to that of John Smith’s in the 17th. It was copied and imitated and used as the foundation for many other maps of the region.

This map depicts north at the top, and its borders, while ambitious in the westward direction, don’t appear unrecognizable to the modern viewer. Rather than the dramatic illustrations of Powhatan and other indigenous people on Smith’s map, Fry and Jefferson’s depicts a dockside scene showing European commerce and enslaved Africans.

Woodard describes the Fry-Jefferson map as “a different animal” than the maps that came before. Where they are full of a sense of rawness and contact, he says, the Fry-Jefferson map shows a land that has been settled and transformed.

Smith’s map and the Fry-Jefferson map differ in yet another way as well. The Smith map shows two societies coming together in frontier space, Woodard says. For example, Smith marked crosses on the map to show where his direct knowledge stopped and he’d relied on reports from indigenous people to fill in the region’s features. Indigenous names appear all over the region, and it’s clear that indigenous people live there, too. Woodard thinks that the Fry-Jefferson map, on the other hand, very much suggests that Europeans have gained total control of the territory. It shows different people in one society, the names largely European, the orientation pointing north, as with maps of Europe.

Maps tell a story, Woodard says, and with the shift away from west orientation, he sees a shift away from an invitation to settle a frontier. In the place of those older maps, cartographers began making maps with declarations about dominion, sovereignty, and borders. “Englishmen imagine; the map makes it real,” Woodard says, with some irony. Even if a map asserts borders that don’t quite match the reality, he notes that it can be part of a transformative process that gradually makes reality match the map.

Maps of Virginia have always attempted not only to describe physical features of a place, but to tell a story about who lives there and who is supposed to live there. The way they are drawn says something about who the cartographer believes the land belongs to and what it will be used for.

However, Horning notes that there are limits to the power of these stories. Even after being drawn out of maps by Europeans, for example, she says indigenous communities are being recognized as the political, social, and cultural entities they always knew themselves to be. For example, recent federal recognition of Virginia tribes shows that erasure on a page doesn’t always stick, she says.

Knowing that sort of complexity makes it particularly revealing to study this collection of west-oriented maps, as well as the more settled maps that came next. On the one hand, they tell a story of changing physical borders and increasing European control. On the other hand, they speak to the indelible marks left by the region’s original inhabitants, and they give hints of what can be found in the Chesapeake Bay area by looking beyond its apparent borders.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook