Why Does the Australian Flag Still Have a Union Jack?

Canada’s flag, pre maple leaf. (Photo: Josh Graciano/Creative Commons)

When the British Empire established dominion over half the world, the Union Jack became a ubiquitous presence. Whether flown as a national symbol or slapped on the upper left corner of a colony’s flag, the Union Jack was a clear indicator of the extent of Britain’s influence, politically and culturally.

Over the centuries, as the Empire crumbled and colonies gained their independence, these fresh new nations jettisoned the Union Jack from their flags as part of asserting their individual identities. In some cases, this happened swiftly—the United States ditched the Union Jack from its flag within a year of signing the Declaration of Independence. Or it can take almost a century, as happened with Canada, which gained independence in 1867 but didn’t switch the Union Jack for a maple leaf until 1965.

Canada’s flag from 1957 to 1965. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

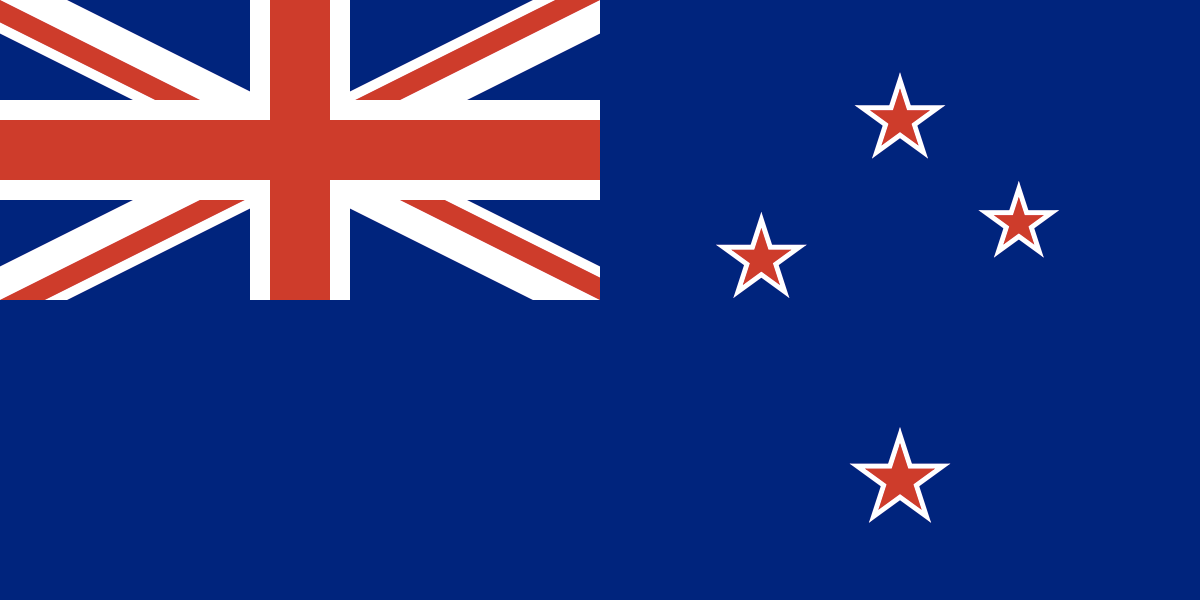

The flags of British Overseas Territories like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands still carry the Union Jack in their corner. But the vast majority of former British colonies have either removed it from their flag or, in the case of New Zealand and Fiji, are currently in the process of doing so. Fiji aims to hoist a new flag design in October, timed to coincide with the 45th anniversary of the country’s independence from Britain. In March 2016, New Zealanders will vote in a referendum in which they will choose to either adopt a new flag—culled from a long list of submitted designs—or keep the current one.

Both New Zealand Prime Minister John Key and Fijian Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama regard their countries’ current flags as outdated colonial symbols that do not reflect their national identities. If New Zealand and Fiji adopt new designs, that will leave just three independent countries whose flags still sport Union Jacks. One is the island nation of Tuvalu, which has a population of about 10,000 and is best known for its .tv internet domain. Another is the tiny South Pacific island of Niue—technically self-governing, but in free association with New Zealand, which handles most of its diplomatic relations. The last is Australia.

The Australian flag, as commentators like John Oliver have gleefully noted, looks almost identical to the colonial relic that is the New Zealand flag. Both designs are based on what vexillologists—those who study the science and symbology of flags—call the “defaced blue ensign”: a Union Jack on a blue background with a few extras on top. The Australian and New Zealand flags are “defaced” with the stars of the Southern Cross, a constellation visible from their positions in the southern hemisphere. (“Defaced” in this context does not connote vandalism, though it certainly does in the eyes of those who advocate a redesign.)

The current New Zealand flag. (Image: Public domain/Wikipedia)

The current Australian flag. (Vector image: Ian Fieggan/Wikipedia)

Each nation’s flag is often mistaken for the other—earlier this month, for instance, it became apparent that the official jersey of the Wallabies, Australia’s national rugby team, had been inadvertently embroidered with New Zealand’s flag. Similar mix-ups occur regularly in international political gatherings—in November, New Zealand Prime Minister John Key spoke on radio of the indignity of being seated beneath the Australian flag at high-level meetings helmed by oblivious organizers.

The Australia-New Zealand relationship is characterized by mostly good-natured rivalry and antagonism, but each country is clear about one thing: the need to be known as separate entities, not lumped together into some amorphous bottom-of-the-world archipelago. (That said, the countries’ interchangeability in the eyes of the world can also be used as an advantage. Australians, for instance, regard Russell Crowe—born in New Zealand; raised in Australia—as a true-blue Aussie whenever he wins an Oscar, but as soon as he makes headlines for assaulting a hotel clerk with a phone, he is suddenly referred to as “that actor guy from New Zealand.”)

In Australia, which became an independent nation in 1901, changing the flag is not an issue of importance—for the government or most of the populace. But there are pockets of passionate campaigners loudly vocalizing their desire to ditch the Union Jack. One long-time activist is Harold Scruby, who in 1981 established Ausflag, an apolitical, non-profit organization that aims to secure popular support for a new national flag.

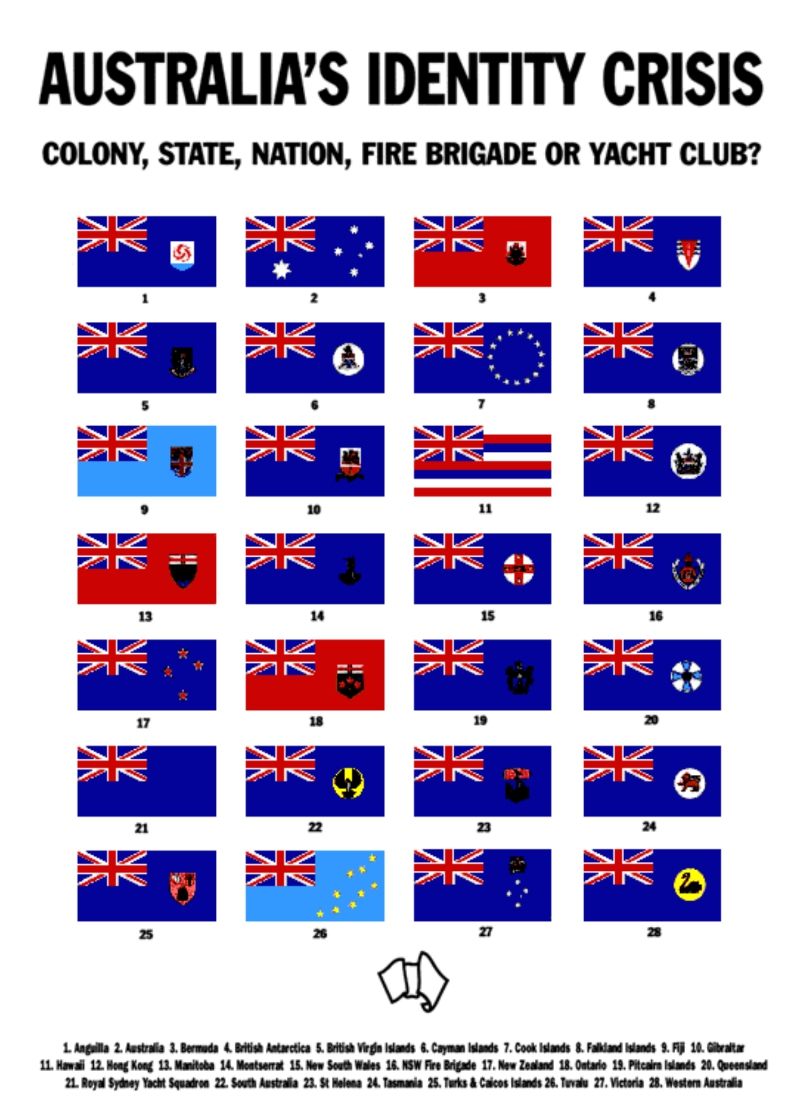

An Ausflag campaign launched prior to the 2000 Sydney Olympics shows some of the flags that resemble Australia’s. (Photo: Ausflag)

“I think it’s about as absurd to have a Union Jack on our flag as it would be for Microsoft to shove an Apple logo on the top left-hand corner of theirs,” says Scruby. In his opinion, instead of making a statement to the world about what Australia stands for, “all we’re doing is promoting their identity, their image.”

Queen Elizabeth II remains Australia’s official head of state, but is regarded as a mere figurehead and performs no governmental duties. This arrangement isn’t unique to Australia, however—it’s also the case for other Commonwealth monarchies like Canada. And Canada ditched its red British ensign decades ago to put forth the maple leaf.

“Canada is passionately in love with its flag and yet passionately remains a monarchy,” says Scruby. So Australia’s reluctance to let go of the Union Jack is not related to its status as a Will-and-Kate-loving monarchy. Why, then, is the flag revamp conversation not happening?

One of Ausflag’s proposed designs for a new Australian flag, featuring the Southern Cross beside green and gold, the country’s official sporting colors. (Image: Ausflag)

Part of the explanation, according to Scruby, is found in Australia’s fractured national identity. Though there is a sense of patriotism in the country—go to any cricket match between Australia and England and you’ll find it—there is also the residual insecurity that comes with being the geographically isolated former colony of a mighty empire.

Eager to show off on the world stage, but too sparsely populated and far away to be an ever-present part of the global conversation, Australia has long been reckoning with a self-image that is alternately boastful and insecure. Physically colonized by Britain and pop-culturally colonized by the United States, the land Down Under doesn’t quite have a cohesive national identity of its own. What flag could sum that up?

Another consideration for Australia is the need to recognize the country’s indigenous population in its official imagery; this has also been a factor in the Fijian and New Zealand flag debates. When the British settled Australia in the 1780s, they declared the nation terra nullius: “nobody’s land.” In doing so, they negated the history and sovereignty of the indigenous population that had been living there for tens of thousands of years.

Centuries later, indigenous Australians, says Scruby, “don’t have a microdot of representation on our flag.” The Australian aboriginal flag, designed in 1971 for the land rights movement, became one of the official “Flags of Australia” in 1995. It is flown alongside the national flag at many buildings in the country.

The Australian Aboriginal flag beside the country’s national flag. (Photo: NH53/Creative Commons)

With Ausflag, Scruby’s dream is ”to have a flag which screams out to the world, ‘Australia!’” he says. “Not ‘Colony of Britain.’”

One of the best assessments he has heard of the current flag, he says, came from Jerry Seinfeld. Visiting the country a few years back, the comedian cracked: “I love the Australian flag: Britain at night!”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook