The Girl Who Jumped Out of a Pie and Into a Gilded Age Morality Tale

Susie Johnson sparked America’s obsession with erotic cake dancing.

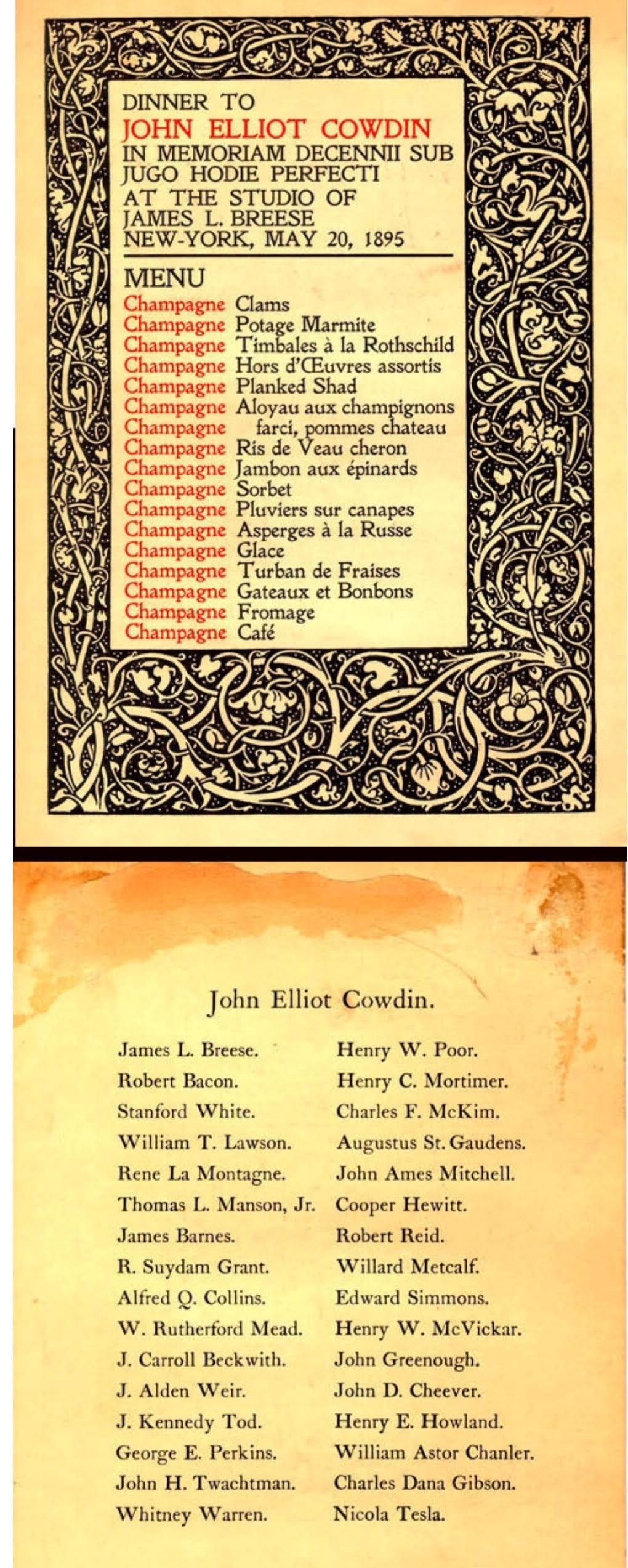

On May 20, 1895, 16-year-old Susie Johnson, wearing nothing but gauze and haloed by a flock of live canaries, burst through the crust of a giant pie. It was polo player John Ellliot Cowdin’s 10th wedding anniversary, and the dinner was lavish: 16 courses from clams to coffee, each punctuated by champagne. Two models entertained the male guests. There was a later rumor—likely apocryphal—that their hair color was coordinated with the wine, the brunettes pouring red, the blondes pouring white. Susie Johnson, dancing out of double-crust pastry, served herself.

In the 1890s, New York was a city with a fever. The slip of island between the Hudson and East River was plush with cash. It poured in from shipyards, freight trains, and factories. It flooded the Manhattan streets. Carriages bounced, crowds pressed, electricity glittered. From Pittsburgh and Omaha, Secaucus and Cincinnati, young women flocked to the city, hoping to make it under the newly electrified lights of the Broadway stage. They ended up modeling for the burgeoning print advertisement industry or working in the chorus line, the factory line, or the line of sex workers on the streets.

Susie Johnson was one such woman. As reported by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, a pioneering yellow newspaper, she had grown up in a working-class family on the West Side. Her career as an artist’s model had begun innocently enough: a portrait here and there. But soon she was taking off her clothes, and then there she was, flesh gleaming in the smoky air, singing “Four and Twenty Blackbirds” for the who’s who of New York playboys. Illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, creator of the Gibson girl, was there; so was inventor Nicola Tesla. (Cowdin’s wife, the ostensible object of the anniversary celebration, wasn’t on the guest list.) Architect Stanford White, whose firm McKim, Mead, and White designed New York City landmarks from the Brooklyn Museum to Columbia University, also attended. According to The New York World, he was the one who cooked up the idea for Johnson’s performance.

It wasn’t the first time in Western history a person—or a live bird, for that matter—had emerged from a large baked good for the entertainment of a feasting elite. Medieval Europeans stuffed pies with live frogs just to watch them hop out. By 1474, an Italian cookbook included instructions on how to fill a large pie with birds, which burst into flight upon the pie’s slicing. In England, this practice is the likely origin of the “Sing a Song of Sixpence” nursery rhyme. People emerged from pies, too: In 1626, the Duke and Duchess of Buckingham gifted Charles I a pie containing the live Sir Jeffrey Hudson, a famous dwarf who would go on to serve in the court.

For the posh set of late-19th century New York City—a coterie as obsessed with public prudery as with private adultery—the “Pie-Girl” dinner was a sensation. “The ‘Girl in the Pie’ at the Three Thousand Five Hundred Dollar Dinner in Artist Breese’s New York Studio,” declared the New York World, above an illustration of Johnson thronged by besuited men, spread like a Venus in pastry. The picture was as scandalous as the dinner’s cost: more than 2,300 times the daily wage of a day laborer.

In the New York World illustration, architect Stanford White stands to Susie Johnson’s left, wielding a large kitchen knife as though about to carve her. According to the article, shortly after the party, Susie Johnson posed “by electric light” at an artist’s studio, a euphemism for sex work, and went missing soon after. “Poor Susie Johnson, dazzled by the lavish compliments and surprised by the liberality of her distinguished patrons,” reported the World. “Perhaps this article will bring Susie Johnson home to her parents and put a stop to the midnight revels in New York’s fashionable studios.”

It didn’t. In 1907, another New York World article revisited the Pie-Girl Dinner, this time as an unheeded warning against the dangers of sexual excess. Susie Johnson, the article said, had faded into anonymity; but Stanford White was dominating the headlines. He had been murdered by the husband of another young woman, Evelyn Nesbit, who said White had raped her. Splashed across yellow newspapers, detailed in a pulp novel, dramatized in Hollywood, and told in popular histories to this day, Stanford White’s rape of Evelyn Nesbit, and his eventual murder, embodied the Gilded glamor of the turn of the century City—and the violence done to working class women such as Nesbit and Johnson.

White offered to make Nesbit’s career, to care for her, and to pay her and her mother’s expenses. He was 47 and married; she was 16 and a chorus girl. The first time White invited Nesbit to his 24th Street apartment, one of many he owned in the city, he brought her to the top floor, where he had rigged a velvet swing to hang from the ceiling. White sat Nesbit on the swing and pushed her: his hands on her back, her legs straining. One night shortly thereafter, White brought the teenager to his bedroom, gave her a glass of spiked champagne, and raped her. Nesbit woke naked to her blood on the sheets. “Now you belong to me,” White had told her, holding her afterwards.

Nesbit told no one about the rape until a few years later, when she confided in her soon-to-be-husband Harry Thaw. But Thaw also had a reputation. It was rumored he beat working class girls with dog whips and soaked them with boiling water until they scalded. He couldn’t stand that Stanford White had “ruined” his wife, so on June 25, 1906, at an opening performance in the very Madison Square Garden theater that Stanford White had designed, Harry Thaw shot and killed him. “He ruined your life, dear,” he told Nesbit as a fireman marched him out of the theater, his gun still hot from the kill. “That’s why I did it.”

The ensuing courtroom drama was declared the trial of the still-young century. Unlike so many women of the era, Evelyn Nesbit had a chance to tell her story, narrating her rape to the courtroom and answering accusatory questions with dignity. Afterward, Thaw was sent to a mental asylum. Nesbit struggled with addiction, yet continued to perform and teach until her death in the ‘60s.

Stanford White, meanwhile, was buried in a Long Island cemetery. But the real monuments to his memory lie all over New York City, in the soaring columns of the Brooklyn Museum and the shadow of the white marble arch in Washington Square. Nesbit was never a very good actress, says Simon Baatz, a City University of New York historian who wrote a book on the case. She’s most remembered not for her work, but for her rape. Stanford White, meanwhile, is remembered not only for the violence he did or the violence done to him, but for what he created.

According to newspapers, even White’s high-profile murder didn’t do much to dampen the reputations of other elite men who may have been guilty of similar crimes. “Stanford White is dead,” The New York World reported in its 1907 retrospective, printed during the height of Harry Thaw’s murder trial. “But most of the guests of that dinner are alive and are holding positions of honor or at the head of their craft.”

What about Susie Johnson? She is also remembered for her work, at least tangentially. Partly in response to the notoriety of the pie-girl incident, women dancing out of cakes became a popular erotic trope. Debbie Reynolds did it in Singin’ in the Rain; Mad Men-era executives hired women to do it for corporate parties; Bachelor contenders do it to this day. As for Johnson’s life, the archives don’t tell us much. The 1907 retrospective reported that she eventually married, but also that when her husband discovered that she was the girl from the pie incident, he left her. She died young and a pauper.

Baatz says there’s no evidence to certify this. Yellow papers, after all, regularly made things up. For all we know, Johnson lived a long, happy life. But as far as the official record is concerned, Susie Johnson jumped from a giant pie into history, and then—like so many women remembered as side dishes to someone else’s story—promptly jumped back out.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook