Where Should Robots Go When They Retire?

Behind the push to create a robot museum in Pittsburgh.

The Trojan Cockroach spent many years in a basement. (Photo: Daniel Pillis)

Most robots, when their creators are done with them, meet one of two fates. Either they’re stashed away, in some corner of a lab, closet or basement, or they’re cannibalized to make another robot. A robot part can cost tens of thousand of dollars, and some robotics researchers, who tend to be focused on the future, rather than the past, do not hesitate to eviscerate an old robot to create a new one.

“We have open labs here, and anybody can pretty much touch anything,” says Chris Atkeson, a robotics professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “If late at night someone decides ‘I need that,’ there’s nothing to stop them from going at it.”

Atkeson, though, has kept his robots. (“I’m a hoarder,” he says. “I save everything.”) Lately, he has been thinking about how to save other robots, particularly those created in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when the field was taking off. He has begun planning for what could be America’s first dedicated Robot Museum, and acquiring vintage robots for an eventual collection.

The Trojan Cockroach in its heyday. (Photo: Courtesy of Daniel Pillis)

The idea for a museum started, indirectly, with the Trojan Cockroach.

The Trojan Cockroach spent years, disassembled, in a basement in Pittsburgh, where its creator had stashed it. Ivan Sutherland had made the robot—a six-legged machine that could walk and carry the weight of a human being—as a sideline, in the 1980s, because he thought it’d be fun.

One day Sutherland’s son got in touch with Carnegie Mellon, where the Cockroach was created. The family was moving, and he wanted to know: Did the Robotics Institute want his father’s robot?

Atkeson thought they ought to save it, and so the Cockroach returned to Carnegie Mellon in parts. Atkeson shoved it into a basement hallway, where, in the spring of 2015, Daniel Pillis found it.

Pillis is a graduate student and artist-in-residence at the Robotics Institute, and he was drawn to the robot. The Cockroach had an alien quality to it, and a startling aesthetic. When he came across it, strewn along 15 feet of hallway, his first thought was: Where can I put this? How can I use this?

“I thought it was garbage,” he says. “I was ready to just pick it up.”

But then Pillis found out more about Sutherland—how he had created a pioneering computer graphics program, how he had worked with one of the founders of Pixar on an early version of virtual reality—and felt like he had learned a secret, an entry in the history of robotics and computer graphics that he wanted to share.

Soon, the robot was in his studio. He took it apart, and started cleaning it. His mom had restored old cars, and his dad owned a junkyard, so it had always been natural for him to take apart machines and figure out how they worked. He got in touch with Sutherland, who started overseeing the project, and in January of 2016, the Trojan Cockroach went on display at the university.

It still couldn’t walk. But, after many years, it had escaped the basement.

A part of the Cockroach on display. (Photo: Daniel Pillis)

Atkeson had started thinking about preserving the history of his field after robotics pioneer Joseph Engelberger died, at the end of 2015, and Pillis’ work prodded him to take action. California has a computer history museum, and some early robots live there. But there is no dedicated robot museum.

Over the past few months, Atkeson has been getting in touch with colleagues who might have saved the robots they made in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Some of what he’s heard are “horror stories”—a robot that was saved for decades before being thrown out, another that was lent to students who took it apart, another that was destroyed in a flood.

Already, though, he’s saved one early robotic arm. When he contacted the creator, he was told the order had just been given to scrap one of the earliest version ever made. But the deed had not been done, and that particular robot was spared.

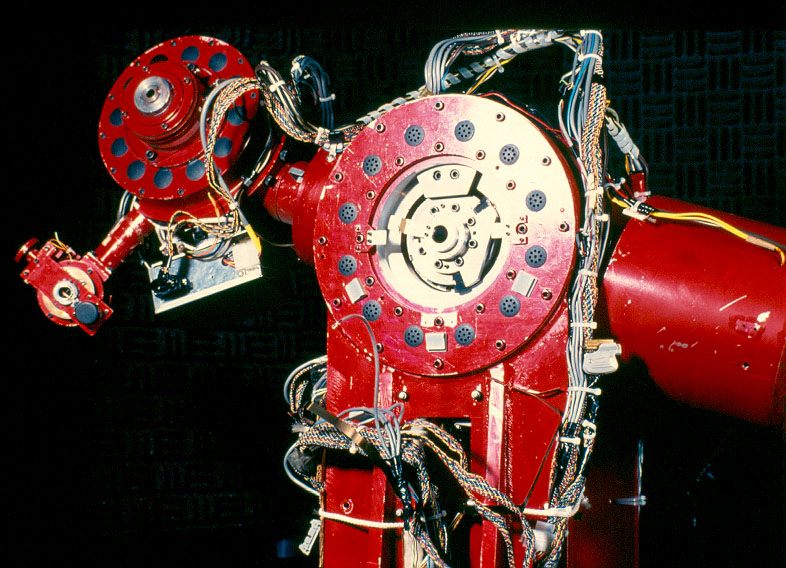

An early robot arm. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Atkeson)

Atkeson says he’ll soon have collected about 20 robots, and is thinking the next step could be creating a virtual museum, so that people can see and interact with them. One day, if there were funding for it, the robots could get a dedicated physical space of their own, where no grad student could steal their insides.

“I have an ex-student who is a science fiction writer,” says Atkeson. “He reminded me that it’s important to have robot museums, because, in many science fiction stories, that’s where you get the part to resuscitate some old thing and save the day.”

Robot museums are also, he notes, the place where an old robot awakens and goes on a rampage. But, to save the history of robotics, that may be a risk worth taking.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook