How Ancient Tooth Plaque Solved the Mystery of the Banana’s Trans-Pacific Journey

3,000-year-old microparticles prove the fruit traveled across the ocean with early Pacific Islanders.

A typical day for Monica Tromp might include scraping tartar off 3,000-year-old human incisors. “It’s basically like being a dental hygienist for the dead,” says Tromp, an Affiliated Researcher at New Zealand’s University of Otago, about her work studying ancient Pacific Islanders’ diets.

The hot, humid climate of places like Vanuatu, an archipelago 1,100 miles east of Australia, makes it notoriously difficult to find archaeological plant and animal remains. So for the past several years, Tromp has turned to an unlikely treasure trove of culinary data on early Pacific Islanders’ diets: the calcified plaque, called calculus or tartar, left on ancient human teeth. Now, in a new paper, Tromp and her fellow researchers have solved an agricultural mystery that has puzzled archaeologists: the migration of the banana.

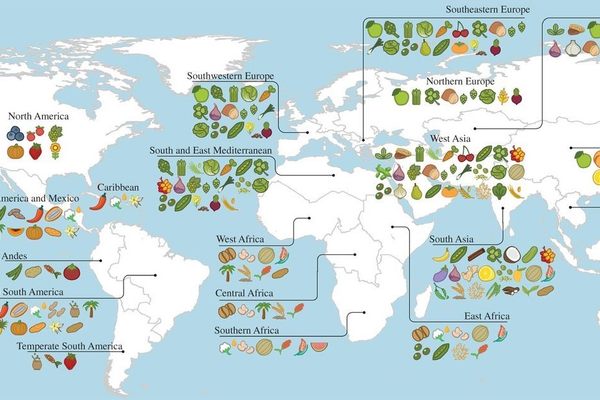

Bananas are staple crops across the Pacific Islands. Researchers have long suspected that the earliest mariners brought the fruit, along with other staples such as taro, yams, chickens, and pigs, with them when they first began navigating canoes from Southeast Asia across the Pacific 3,000 years ago, settling uninhabited islands along the way.

“They supposedly brought this whole transported landscape,” Tromp says. But the difficulty of finding preserved plant or animal matter in humid island climates meant that archaeologists lacked material proof that Vanuatu’s earliest settlers carried specific fruits, including bananas. Instead, researchers relied on contemporary linguistic evidence: Pacific Islanders, for example, had very similar words for different foods, suggesting a single ancient origin for the plants.

Now, Tromp and her team have used banana microparticles, preserved in teeth from a 3,000-year-old human burial site, to show that bananas began their trans-Pacific journey with Oceania’s earliest settlers. Their find supports the theory that early settlers traveled with a floating plant and animal menagerie. It also adds credence to the increasingly accepted idea that indigenous people across the world actively shaped rainforest ecosystems once assumed to be largely untouched by humans.

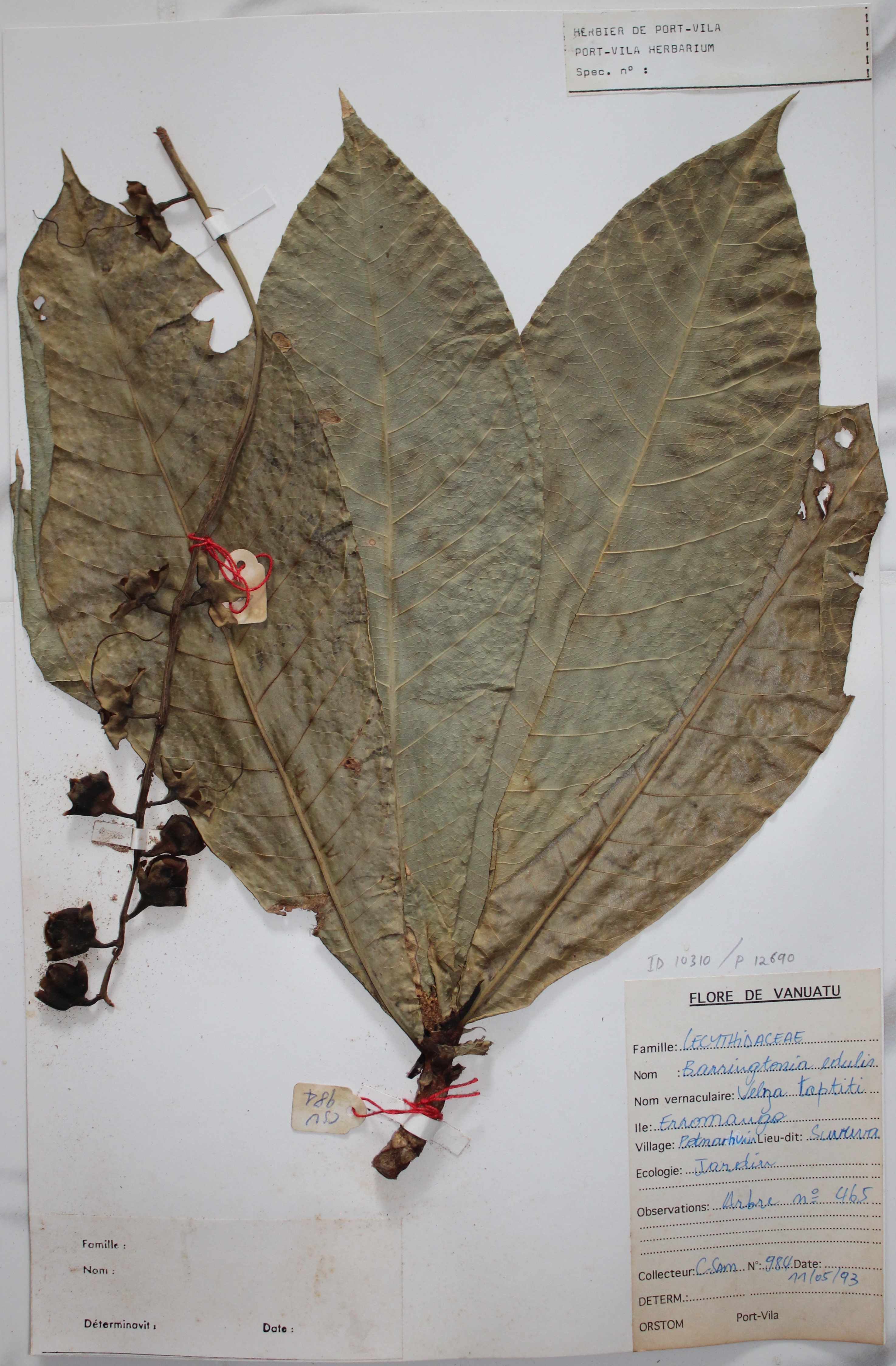

The trail of evidence starts in Teouma, a cemetery of the ancient Lapita people who first settled Remote Oceania, the archipelagos east of the Solomon Islands. Located on Efate Island, in present-day Vanuatu, the cemetery is a rare example of Lapita material culture, well-preserved because the bodies are buried in limestone. The skeletons at Teouma had been decapitated, likely as part of rituals related to ancestor worship, says Tromp. But their teeth were left behind. After initial excavations in the early 2000s, researchers stored the remains at a museum in Vanuatu. That’s where, more than a decade later, Tromp found them, and began investigating the tales their teeth could tell.

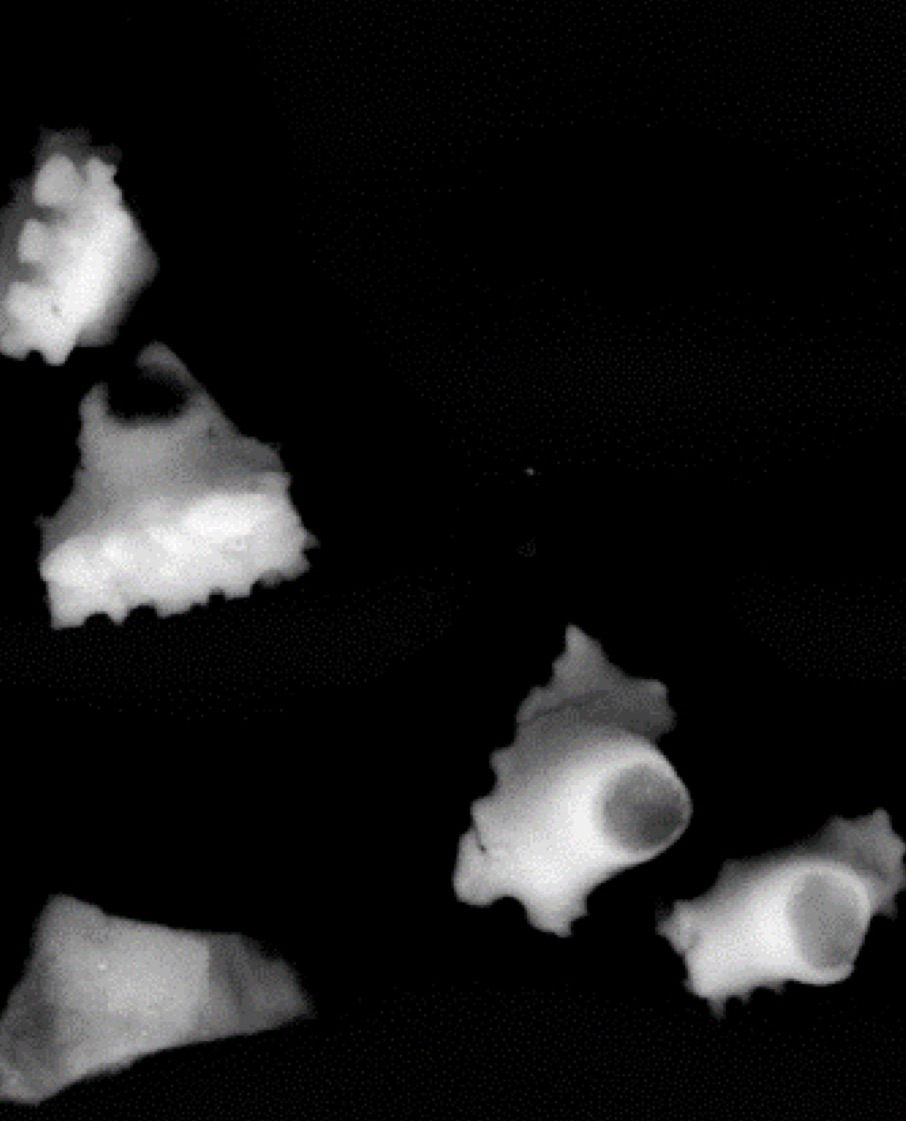

While tartar is a bane for contemporary dental hygienists, it’s a boon for ancient ones. Throughout our lives, mineral microparticles from the plants we eat, called phytoliths, get trapped in our plaque. When our plaque calcifies, it preserves the particles, Tromp writes, “much like the infamous Jurassic Park mosquito in amber.” To study these microparticles, Tromp scraped the calculus off the ancient teeth and treated the substance with a weak acid, which degraded the tartar, leaving only phytoliths behind.

By comparing the phytoliths to microparticles from contemporary plant specimens, Tromp and her team were able to identify a range of plants from the burial site, including banana leaf and seed phytoliths. “They look like little, tiny volcanoes,” Tromp says. The presence of both leaves and seeds suggest Lapita people used bananas for a wide range of purposes, from eating to cloth- and jewelry-making. Tromp has examined calculus from sites all over the world, but the number of phytoliths at the Lapita site was particularly notable. “It’s the first time I’ve ever seen such a high concentration of this kind of microparticles,” she says. This suggests that Lapita people engaged in substantial use of culinary and medicinal plants, and that they had a greater hand in shaping Vanuatu’s rainforests than archaeologists previously thought.

Tromp’s research has changed her perspective on Vanuatu’s landscape as well. Now, when she walks through the dense, seemingly wild jungle, she notices yam plants, taro, and fruit-bearing trees, all part of an agricultural legacy first established by early Lapita settlers. It’s a big shift in perspective brought about by tiny particles, and an unlikely time capsule: human teeth.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook