A Fetus Can Turn to Stone in Its Mother’s Body and Go Undiscovered for Decades

“Stone babies”—or lithopedions—are incredibly rare.

In 1554, in the town of Sens, France, Colombe Charti went into labor. It was her first pregnancy, and she had carried the fetus close to term. But something went wrong. Though her contractions stopped, Charti’s baby was never born.

For three years after that, she lay in bed, recovering, and for the rest of her life she would have strange pains in her abdomen. Her neighbors believed (quite logically) that the baby was still inside her. After she died 28 years later, her husband enlisted two surgeons to autopsy her body in hope of discovering the truth.

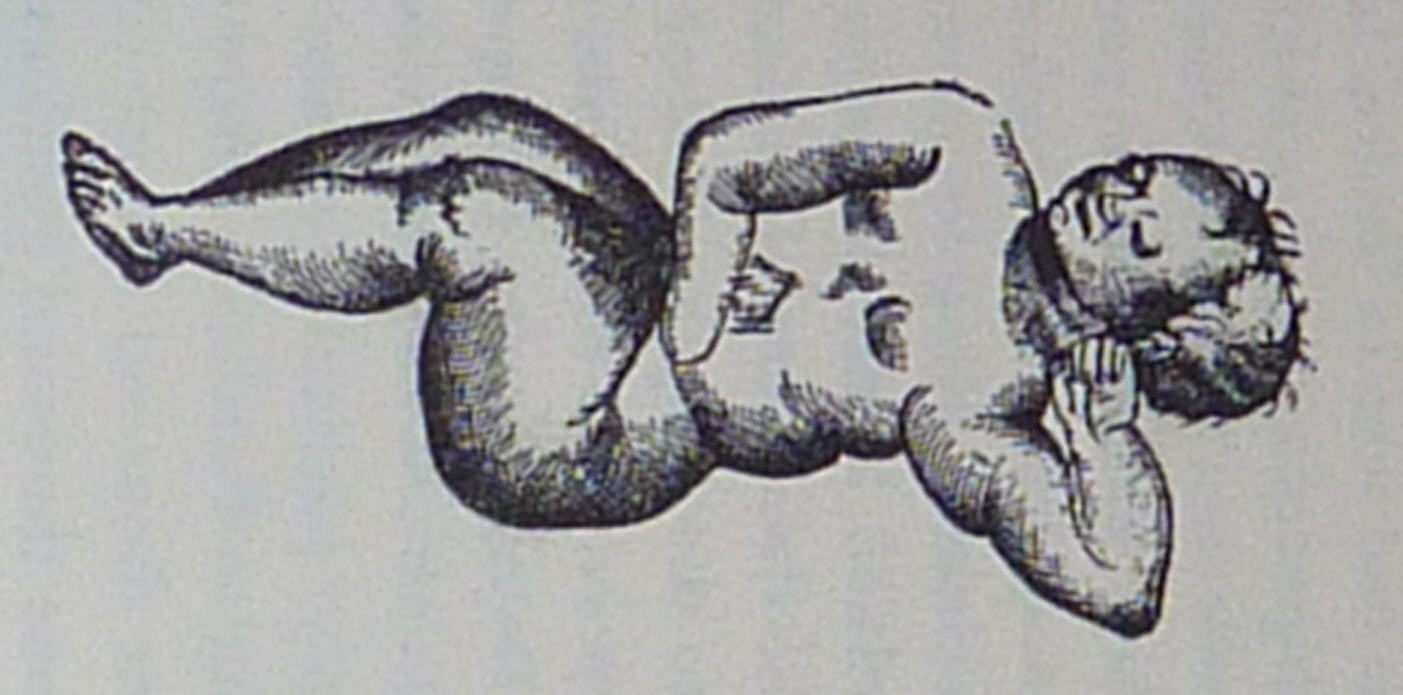

The object that the surgeons found inside Charti was hard and roughly ovoid. Though at first the surgeons thought it was a tumor of some sort, when they broke through the scaly outer shell, they found shoulders and a head, two arms, knees bent towards the chest, legs and feet, fused together. It had one tooth, and if it had been born, the fetus would have been a girl with a full head of hair.

The Sens baby is one of the earliest extensively documented cases of a lithopedion—a never-born “stone baby” that calcifies over time. It’s a very rare condition: There are only 300 or so known cases, going back to prehistory. Lithopedion most often form after pregnancies in which the fetus grows outside the uterus and is too large to be reabsorbed by the mother’s body. Instead, it dies unborn, and can remain in its mother’s body for the rest of her life.

The oldest known lithopedion, which has been dated to more than 3,100 years ago, was found at an archaeological site in Texas, with its limbs skeletonized and “bound by a thickened, calcified membrane,” the researchers who identified it wrote when they reported the find in 1993. The first documented case in medical literature dates back to the 10th century, in an influential guide to surgery written by the Andalusian surgeon Al-Zahrawi.

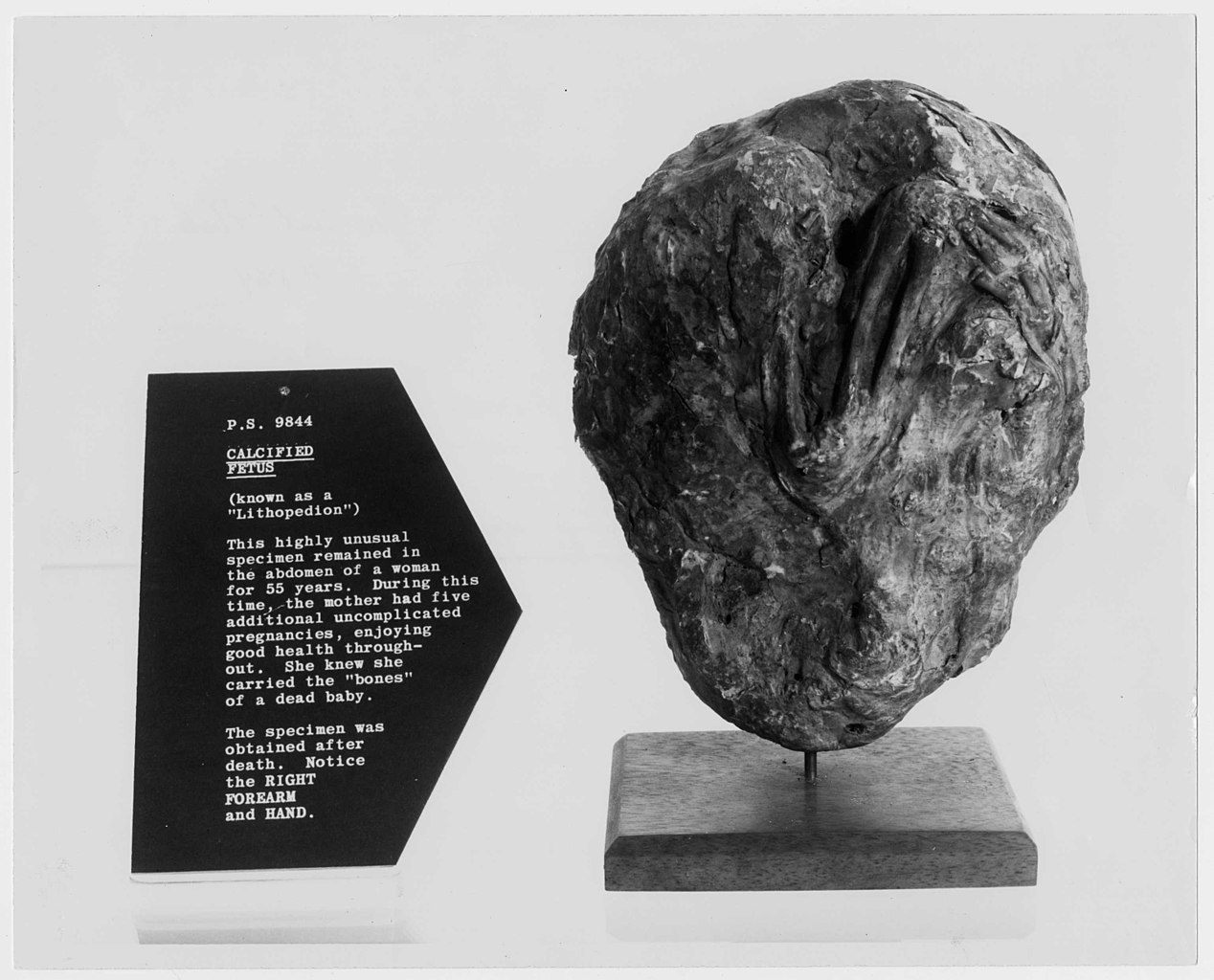

In the 16th century, the Sens lithopedion was treated as a curiosity, passed from hand to hand over the following centuries, as medical experts debated the mechanism of its creation, as rheumatologist Jan Bondeson details in an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. In the three centuries after the Sens case, 46 more were documented in medical literature. Physicians discovered that lithopedions formed in three different ways—the surrounding membranes calicify while the fetus does not, the membranes rupture and the fetus calcifies, or both the membranes and fetus calcify, as in the Sens case. Often, these cases weren’t discovered or documented until late in the lives of the women carrying them. A 1949 review of cases found that of 128 documented cases, nine of the women spent at least 50 years with a lithopedion in their abdomens.

Abdominal pregnancy, in which a fetus grows outside of the uterus or the fallopian tubes, represent only one out of every 10,000 to 30,000 pregnancies. Of those rare occurrences, fewer than 2 percent end up producing lithopedions. Lithopedions have become even more uncommon as prenatal care has improved. Abdominal pregnancies pose unique risks to both mothers and babies, and they may be terminated early on. In any case, they are often closely monitored, and a fetus that did not survive would be removed before it could begin to calcify.

Still, there are modern cases, most often the result of pregnancies decades before. In recent years doctors have treated a 70-year-old woman who carried a lithopedion for 35 years, a 75-year-old with one formed 46 years before, and a 92-year-old woman who had spent 60 years with this condition.

The most famous lithopedion—the one from Sens—eventually disappeared. The surgeon who extracted it eventually sold the specimen to a merchant, and from there it passed through the hands of a goldsmith and of a jewel merchant to King Frederick III of Denmark, who bought it in 1653. Over the following decades, the lithopedion grew more fragile, and lost an arm and its jaw. In the 19th century, it ended up in the Danish Museum of Natural History, where it was lost or discarded.

Some universities and medical museums still have lithopedions in their collections, though—a macabre reminder of the mysteries the human body can hold and hide during a person’s lifetime.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook