The Indie Video Games Bringing South and Southeast Asian Food to Your Screen

Cook for vampires or restore lost recipes with these diverse games.

Video games use all kinds of techniques to evoke a response from players. Often, it’s an appeal to the senses: a jumpscare, a vibrating controller, evocative music. But pixels have a hard time representing smell and taste. Plenty of video games feature food nonetheless, whether that means pizza as a power-up (think the arcade classic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Turtles In Time) or as a gift to gain the affection of a game character, à la Stardew Valley. With some exceptions (such as the painstakingly rendered dishes in Final Fantasy XV,) food in video games is often an afterthought.

Recently, though, developers and programmers from around the world have made their passion for food playable. In all of these upcoming games, cuisine becomes a tool to explore complex subjects, from immigration and diaspora to family and love.

Venba

Canada and India

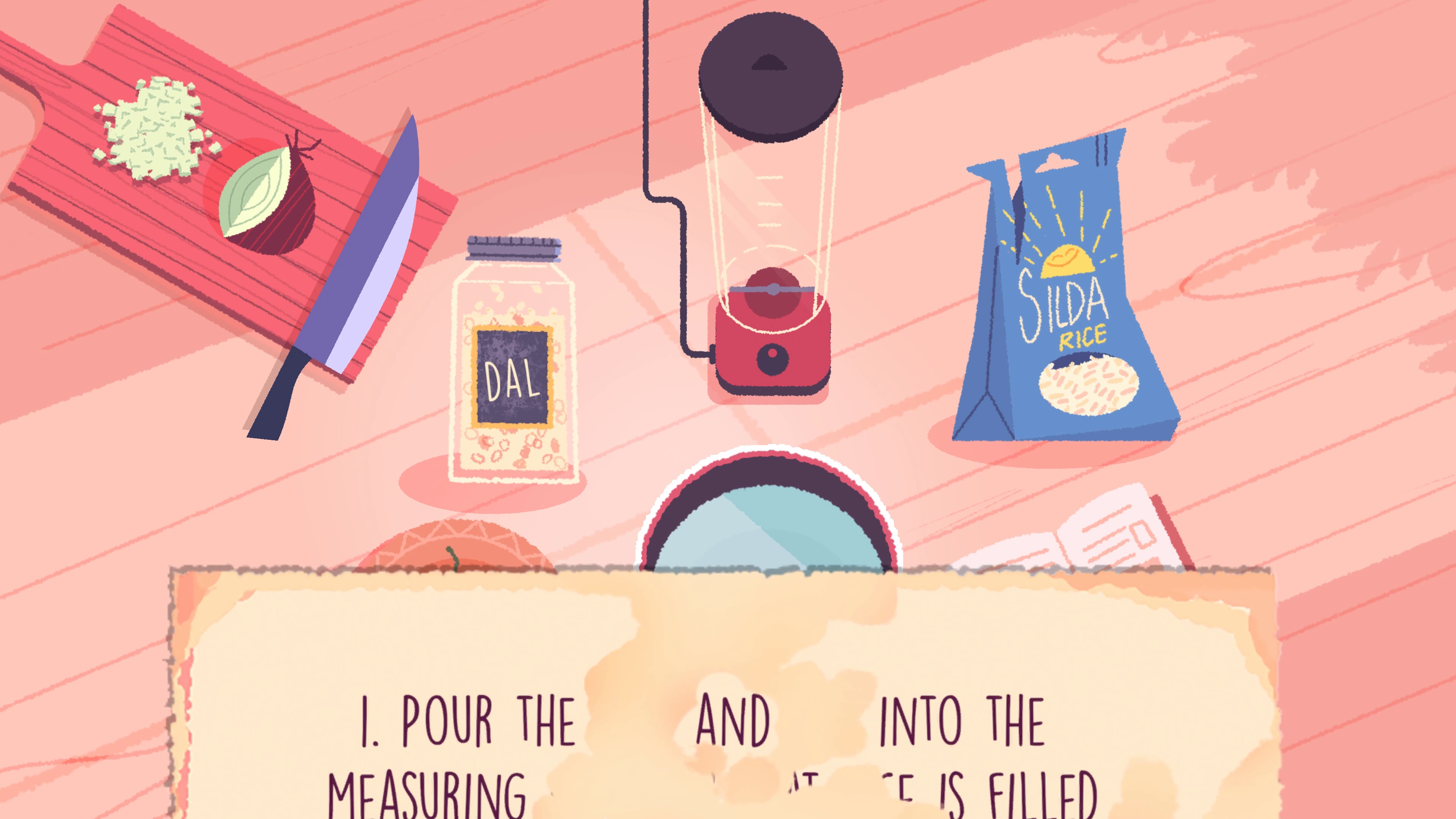

The connection between food and home is at the heart of Venba, a narrative game by the Toronto-based studio Visai Studios. The game follows Venba, a Tamil woman from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, after she immigrates to Canada with her family in the 1980s. Over the course of the game, players must restore the recipes in Venba’s cookbook, which was damaged during the move. Through puzzle minigames, players assemble dishes while filling in the blanks of Venba’s recipes along the way.

For Visai Studios’s lead designer, who goes by his online name Abhi, developing the game was a rare opportunity to walk players through the challenges immigrant parents face when teaching their children about their homeland. Abhi mentions one scene that revolves around a dish called puttu, where coconut and rice are steamed together in a cylinder. “So the scene that we wrote is that the kid wants a pizza,” he explains. “And the mom is struggling… because she’s afraid that she’s losing him to this Western world.” Venba captures her son’s interest by comparing puttu to a rocket ship, says Abhi, “and this whole family has a moment.”

The game is designed as an introduction to Tamil food culture for those who know nothing about it, but it’s also targeted towards young immigrants who didn’t grow up in their homeland. Abhi, who works as a mobile game developer by day, developed the idea after watching other works that centered the Canadian immigrant experience, such as the show Kim’s Convenience and the Pixar short film Bao.

Venba is likely the first portrayal of Tamil food in a video game. As a result, Abhi says that there was some self-induced pressure to portray Tamil culture both accurately and vibrantly. For help with recipe-testing and demo-ing the puzzles, he reached out to both his friends as well as the Tamil community in Toronto. He also tapped Toronto-based Tamil musicians for the video game’s soundtrack. Sound, he says, was a vital ingredient when it came to making the game feel authentic. “From what I’ve noticed, cooking is not silent in India,” Abhi says.

When the trailer dropped in December 2020, reactions were overwhelmingly positive. “We didn’t expect the reaction we got,” Abhi says, adding that afterwards, game industry notables reached out to offer their support, including the developer Rami Ismail and Chandana Ekanayake, the co-founder of Outerloop Games. “It was almost like the video game community was completely ready for this game.”

After School Afterlife

Singapore

Heather and Megan Lim, two sisters from Singapore, don’t work in video games. Megan is a law student, and Heather works in a bank. But both sisters have a passion for games, and, during quarantine, they decided to make a game based on the culture of the Peranakan Chinese, the descendants of the first wave of Southern Chinese traders who intermarried with local Malays in the region.

The result is the upcoming platformer After School Afterlife. In the game, players must escape a Peranakan Chinese mansion that sits between the worlds of the living and the dead. But along the way, the game features both Peranakan and Singaporean Chinese traditions, especially those that relate to food.

Peranakan cuisine, with its varied cultural roots and emphasis on intricate details, is notoriously difficult to master in real life, and even harder to recreate on-screen. “My parents got a bunch of Peranakan dishes for my sister to try out,” laughs Heather. “And she would take photos and write a lot of notes for me.”

Both sisters considered it important to include context for players encountering Peranakan culture for the first time. But it was also an education for them. “We eat this food, but we don’t necessarily know that much about how it’s made or the history behind it,” Megan explains. “So we also research it and learn, and maybe other Southeast Asians will learn a bit about the dishes of cultures they might not think too much about.”

But in After School Afterlife, players learn by interacting with ghosts and monsters. The kitchen, for example, is occupied by hungry Chinese vampires, jiangshi. Players must feed them by making ayam buah keluak, chicken with tamarind gravy and buah keluak nuts. In another mini-game, players enter a haunted coffee shop, or kopitiam, to mix iconic drinks like kopi-o and teh tarik. Many of the facts about food and culture acquired during gameplay are stored in an in-game diary for reference.

The Lims say that playtesters have loved seeing their food and culture in game form, especially how the soundtrack incorporates the cries of an infamously loud local bird. Singaporean playtesters have also expressed interest in learning more about the Peranakan culture in their own backyard. That tracks with Heather and Megan’s motivation for making After School Afterlife, especially after growing up without much representation of their culture on the page or onscreen. “So that’s part of it,” Heather says. “Let’s just have this fantasy novel that we always wanted as a kid, put in the medium that we also enjoy.”

-41413e23-403d-4255-a911-19ba3fae6f1d.webp)

Lutong Bahay and Soup Pot

Philippines

Filipinos are rightfully proud of their cuisine, which is perhaps why there are currently two buzzy food-themed Filipino games.

Philippines-based teams Team Meowfia and Senshi Labs released their minigame Lutong Bahay in December 2020 to great acclaim. Lutong Bahay, which means “home-cooked” in Tagalog, follows young Maricela who must learn about iconic dishes from across the Philippines in order to inherit her grandmother’s carinderia (food stall).

Players are tasked with cooking a range of dishes, such as lumpiang ubod, a spring roll filled with julienned palm hearts, shrimp, and pork, and sisig, pork cooked with onions and chili peppers. As for why they chose food as the subject for their game, the answer is simple. “For most people, food is something we turn to when we are in need of comfort,” the team wrote via email. “Filipino culture is centered around this fact.”

This sentiment is echoed by Chikon Club, the independent Southeast Asian company who also partnered with Senshi Labs on Soup Pot, a video game aiming to capture the creative pandemonium of home cooking. While not as narrative-focused as Venba, After School Afterlife, or Lutong Bahay, it’s just as artistically thoughtful as its brethren, allowing players to handle 3-D renders of hundreds of ingredients. Those ingredients are used to make dishes from around the world, but the main focus is Filipino food. The game also lets you play with ingredients in a way that might not be possible in real life. Players can crack an egg or fling it at a noisy neighbor.

The game is scheduled to be released later this year, but it’s already attracted a lot of attention, says technical director Gwen Foster, especially from the Filipino diaspora abroad. But for the team, creating the video game was a way to further connect with not just people from the Philippines, but also to a wider audience. “Food is both a love language and a means to connect and communicate with different people,” Foster says.

Connection is the theme of all these games, several of which were drafted or designed in the midst of the pandemic. (Soup Pot even takes place in the midst of quarantine.) During this profoundly isolating time, food still retains the power to deepen or create brand-new bonds. Heather Lim has noticed that, when early playtesters finish After School Afterlife, they’re eager to learn more about the Peranakan culture as a whole, even if they can’t travel to Singapore right now. “They’ve been introduced to this food,” she says. “And now they want to come visit.”

As for Abhi, he hopes that his game will make people look for connection a little closer to home. “When I talked about this game to one of my friends, she said, ‘I like the story. I feel like people will call their mom after they play it,’” he says. “I think if people call their mom after they play it, I’m happy.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook