Scandinavia’s Most Metal Sound Systems Are Made of Horse Skulls

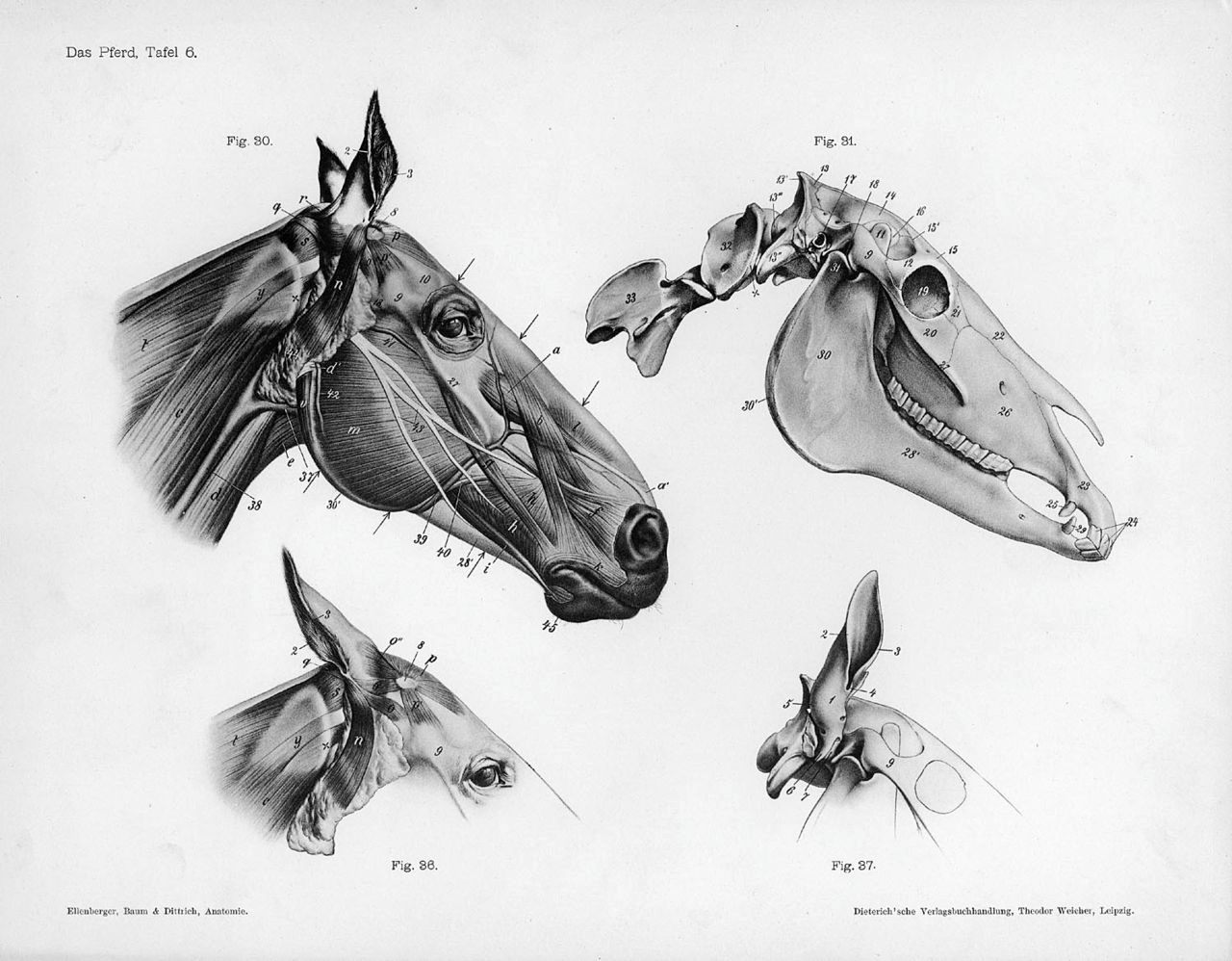

(Image: University of Wisconsin Digital Collections)

When you renovate a house, you expect to find little bits of its history. Maybe an old photo lost behind the refrigerator, or a hideous shade of paint lurking under the wallpaper. What you don’t expect is two very large, nicely preserved horse skulls buried under the floors.

That’s exactly what Colm Moriarty’s aunt found when she was having some work done on her house in the 1980s.

“The floor was all flagstones. They were taking up that floor and putting in a concrete floor instead, and as they took up the flagstones, right in the center were two horse skulls,” says Moriarty, who was seven years old at the time. “I remember my dad saying that’s what they were, and it stuck in my head.”

Twenty years later, Moriarty was working as an archaeologist on an excavation of two medieval houses near Dublin. Guess what he found.

“As we took up these clay floors, more horse skulls started turning up,” he says. “One house just had the one skull, and the other actually had eight skulls in the floor. The minute I saw them, I just thought of my grandaunt’s house.”

This sounds like the set up for a B-grade horror movie, but horse skulls have actually been found under buildings—dating from Iron Age well into the 19th century—across Northern Europe, from the UK to the Baltic states. And they didn’t wind up there by accident. That would be the case with smaller objects like coins, writes archaeologist Sonja Hukantaival, “but it is obviously not so easy to accidentally lose a horse in your house.”

(Photo: Wer?Du?!/Wikipedia)

Instead, Hukantaival says, the skulls were deliberately placed within buildings as “foundation deposits.” Hukantaival is doing her doctoral thesis on foundation deposits, and according to her research, people have been concealing various objects—from everyday household items to DIY counter-magical devices—in buildings for pretty much as long as permanent buildings have been around. At different times and in different places, the meanings of these deposits and the practices surrounding them have changed, but using domestic animals as deposits seems to be a constant, and the horse appears especially often.

But just what were these skulls deposited for? There are two ideas. One is that they brought good luck to the building and its inhabitants, and protected them from natural and supernatural threats. Like the horse shoes that some people keep in their homes, the horse skull was thought to bring luck and expel evil. A horse skull foundation deposit, Hukantaival explains, would have ensured fertility, health and a good crop, and guarded against sickness, death, fire and lightning. In the folklore of some countries, like Finland, horse skulls and other foundation deposits were also said to protect against witchcraft when placed at the borders of a house. They could also be used in an act of witchcraft instead of protection against it, Hukantaival says, a deposit secretly placed under someone else’s house would curse the building or steal luck from it.

The other explanation is that they were part of a macabre sound system. The cavities in the skulls amplify and echo ambient noise, and archaeologists think that in some places they were buried under floors to improve the sound when people danced, sang or played music. In the British Isles and southern Scandinavia, presumed “acoustic skulls” have been found in home and churches. In Scandinavia, they also often turn up under threshing barns, where, Hukantaival says, “it was considered important that the sound of threshing carried far.”

A threshing barn, as depicted in the 1820s by Russian artist Alexei Venetsianov. (Image: cAFwpyEuqntdvw at Google Cultural Institute/Wikipedia)

In 1938, the Irish Folklore Commission conducted a survey in Ireland, asking about local traditions surrounding horse skull foundation deposits. In almost every area of the country, people reported knowing about skulls concealed in several houses, usually under the floor in front of the hearth, and all but one of the people who were aware of the custom explained it was a way of improving the sound when people danced. Folklorist Seán Ó Súilleabháin, writing about the survey for the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland in 1945 wasn’t convinced by what he heard, and argued that the practical, acoustic application was a secondary motive, thought up to rationalize the burying of skulls when the original ritual reasons had been forgotten.

Four years later, Swedish historian Albert Sandklef disputed Ó Súilleabháin’s ideas after researching horse skull deposits in Scandinavia. There, the skulls were frequently buried alongside acoustic pots in threshing barns so that a ringing tone was produced when grain was threshed with flails, and the regional folklore had little to say about skulls being used to protect houses. At least in this part of the world, Sandklef concluded, horse skulls were only buried for acoustics and there was no mystical or protective element to them.

Maybe we don’t need to distinguish ritual from practical reasons, though. One could have evolved from the other. “If they were used for acoustic purposes then it seems clear that there was already an association between the horse skull and the aversion of evil and that perhaps this brought an additional benefit to the practice,” says historian Brian Hoggard. “The likelihood is that both uses were known and understood fairly widely by those who were involved in building.”

The two purposes could have also co-existed. In places like Scandinavia where the skulls were not part of home protection folk customs, the noise they made may have been its own form of protection. “In many cultures loud noises are considered to expel evil forces,” Hukantaival says. “So this ‘practical’ custom of acoustic skulls may not be contradictory to magical and symbolic acts at all.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook