How Ukraine’s Museum Curators Are Risking Life and Limb to Document the War

Working to preserve memory, as history unfolds in real time.

When Larysa Kramarenko entered what was left of her brother’s house, a small icon of Jesus Christ hanging on wall was the only thing the Russians had left behind. The invading troops had occupied the northeastern city of Izium for nearly six months before fleeing in panic in the face of a Ukrainian counter-offensive that liberated large swathes of territory in the Kharkiv and Donetsk regions. “They took absolutely everything from his house,” says Tetyana Fiks, a 37-year-old curator at the War Fragments Museum. “Everything, there is nothing there. His sister gave me this, which was on his wall, an icon, a painting. It is small, and it was the only thing that was there.” Her brother had been abducted from the house, tortured for three days, and executed. Fiks and her colleagues traveled there in late 2022. In March of that year, Fiks and two colleagues, Bohdan Cheshik and Andrii Sirchenko, embarked on a museum project like no other they had ever heard of before.

Their goal was to collect fragments, relics of the conflict, from all regions of Ukraine, and then encase them in small transparent cubes made of epoxy resin—some of which could be sold to raise money for humanitarian aid or to support Ukrainian troops fighting on the frontline. The War Fragments Museum was born: ”One cube, one story.” It now has a team of five Ukrainian staff. “When the full-scale invasion started, we decided that we would make audio about stories of people who escaped from an occupied Kyiv region,” Fiks says. “They had the opportunity to rescue themselves, so it’s not just statistics. The stories will have their names and everything. Then we decided that while a story is good, if you could have something that you could touch, it would bring a sense of eternity. So we decided to make these cubes.” The icon from Kramarenko’s wall is one of around 300 objects the team has preserved for posterity.

In my travels through Ukraine as a journalist, I’ve found the many ways that its citizens are collecting, preserving, and documenting evidence of Russia’s invasion. These can range from the individual, such as the family I met in Kharkiv oblast collecting spent rocket shells. Others can be community-based, like the local reporters in Chernihiv who wrote a book about the Russian siege of the city in the first weeks of the war. War Fragments is just one of the numerous ways Ukrainians are attempting to catalogue their story. They are writing history in real time, sometimes at personal risk, as the war continues to rage in the south and east of the country.

An effort like the War Fragments Museum is demanding and dangerous in the region of Kharkiv, for example, which is still heavily mined and contaminated with unexploded ordnance that could take years to clear. Kherson, which the team also visited, is shelled regularly by Russians from across the river. A Russian artillery shell landed just 50 yards from me the last time I was in the city.

The War Fragments project, the creators say, is to demonstrate Ukraine’s unique history and culture. Part of the Kremlin’s justification for the invasion, as laid out in a 2021 statement by Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, has been that Ukraine is devoid of identity, just a renegade province of Russia that needed to be returned to the fold. “For so long, people saw our culture as part of Russia, as part of the ‘Russian world,’” says Fiks. Well, if you want to see Russian world, go to Saltivka!” Saltivka is a district in the north of Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city, that the Russians had tried to storm in the first days of the war. After the attack failed, the invaders placed artillery a few miles from the city gates and leveled large portions of it, killing hundreds of civilians.

From Saltivka, Fiks was given a warped clock face by a woman whose home had been destroyed in an artillery strike. Another object was a pine cone from a mass grave outside Izium, where hundreds of civilians and soldiers had been buried.

These individual projects are intended to complement, not replace, the traditional means of preserving pieces of history, as done by professional museum curators and exhibitions. Several of the War Fragment’s projects cubes have now found their way into the country’s official museums, such as the Odesa National Art Museum, and the artifacts collection in St. Sophia National Reserve. It blurs the boundary between traditional and modern ways of exhibiting and storytelling in a museum.

Traditional, physical museums in Ukraine have also been radically reshaped to tell the story of the invasion. The Pechersk district of Kyiv is known for a huge statue of a woman with a sword and shield, known as the Motherland monument. At its base is the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War. It holds memories of sacrifice from when Russia and Ukraine fought under one banner in what is locally known as the ”Great Patriotic War”—though that moment has since been twisted by Russian propaganda to promote the idea that are the same people and nation, according to Oleksandr Amlekya, a curator at the museum who is also a veteran of the long-simmering conflict in the Donbas region. Amlekya says that this is a myth that must be eradicated. “Ukraine was occupied by Soviet Russia from the start of the 20th century, he says. “The pain of Ukraine was that we suffered under both totalitarian regimes—the Soviet and the German.… We suffered more from Russian occupation, we were only on the Russian side to prevent the German occupation. If we look at the numbers, Ukraine suffered more from the Russian occupation.” He specifically cites the Holodomor (Ukrainian for “death by hunger”) of the 1930s, when Stalin’s government deliberately starved an estimated 3.5 million Ukrainians.

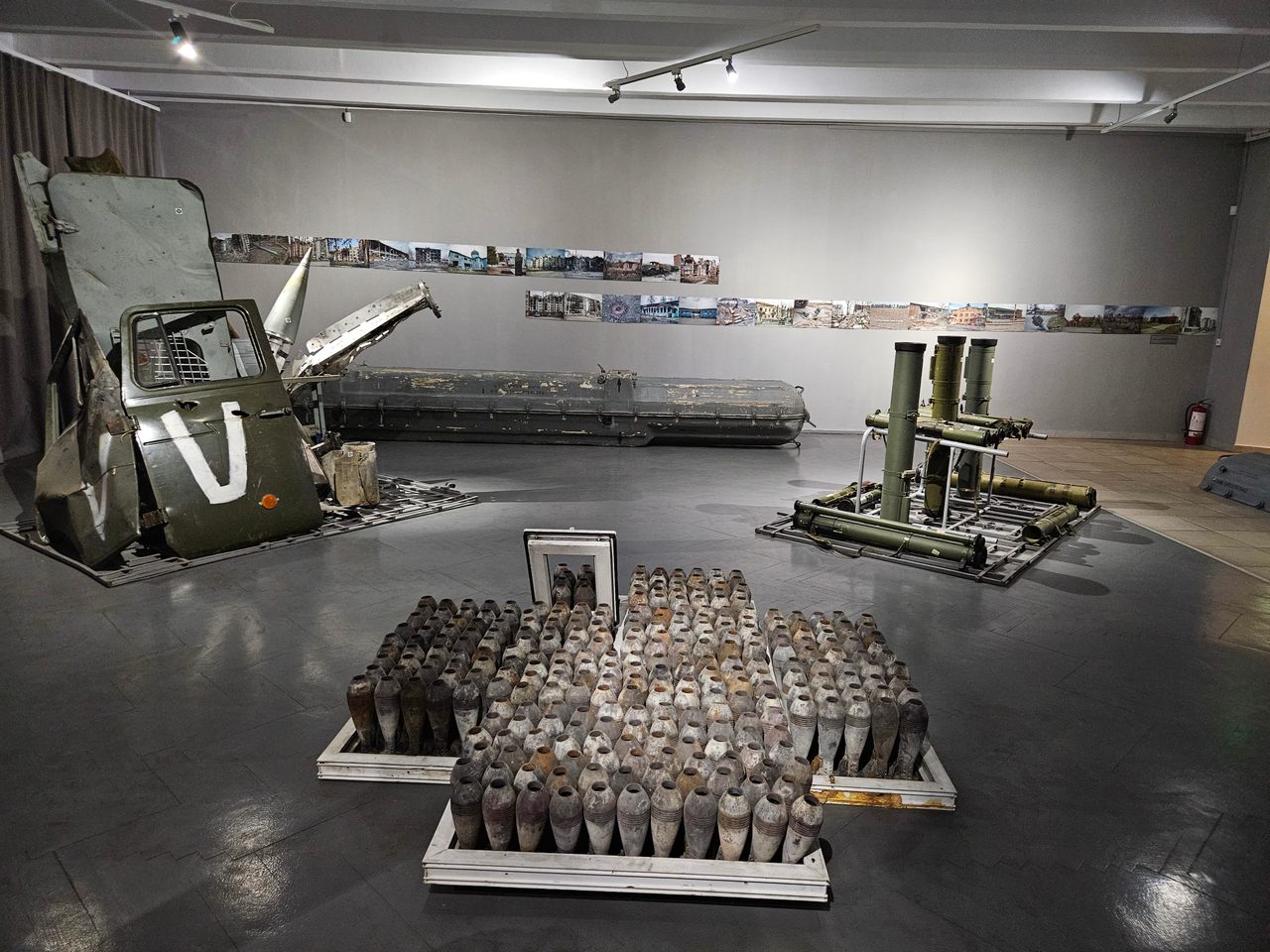

At this museum, everything has been recast by the shadow of the new war. The hammer and sickle on the shield of Motherland have been replaced with a trident, the symbol of the Ukrainian nation. The museum itself is now home to an exhibition called Crucified Ukraine, which tells the story of the Battle of Kyiv that dominated the first month of the war.

Vladimir Ovcharov, a Russian soldier, was just 19 years old when he was killed in the invasion. His passport photo, on display at the museum, has the look of a boy barely out of high school: baby-faced, with a slight gap in his teeth and wispy hair combed across his head. “He’s so young … you’d almost feel sorry for him,” says Yana Troianska, a 28-year-old woman from Mykolaiv, while visiting the museum. But, she makes clear, her sympathy has limits.

The personal documents of other Russian soldiers, as well as captured battle plans and journals, are displayed on tables in the center of the main room. It was an interesting curatorial decision, I thought, in that it actually humanized the invading Russian soldiers who killed tens of thousands of Ukrainians.

Downstairs is a replica of a bomb shelter based on one in Hostomel. The town was notable for being the site of heavy fighting during the first day of the war. The space is scattered with foodstuffs, blankets, and mattresses taken directly from the real shelter. Having visited many of these shelters in frontline towns across Ukraine, I can verify that it captures the experience closely. Ironically, it is used by museum staff and visitors when an air raid alert sounds in Kyiv itself, though many residents have long since started to ignore them.

A television screen upstairs in the museum displays reruns of speeches by Putin and his propagandists on Russian national television, calling for the destruction of the Ukrainian people and denying the country’s legitimacy. The point, the curators say, is to make the link between propaganda and dehumanization, and how it can turn into war crimes.

The yards outside the museum were once dominated by tanks and armored vehicles used by the Soviet Red Army to fight the Germans in World War II. They were briefly recommissioned and used in the defense of Kyiv, although the details of that effort remain secret. Now they have been replaced by a series of destroyed Russian vehicles.

When Russia first invaded in February 2022, museum curators were like all other Ukrainians—focused on survival. Staff at Ukraine’s most recognizable museums and galleries, such as the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in Kyiv, or the National Art Gallery in Odesa, spent weeks evacuating priceless artifacts to western Ukraine, where they would be safer. Curators also took field trips to towns such as Bucha and Irpin shortly after they were liberated to check on collections stored there. Their fears were well founded—the Regional Art Museum in Kherson, a southern city later occupied by the Russians, was completely looted as the Russians retreated.

The museums in their various forms are not just static recollections of events, but have now become part of the Ukraine’s wartime information campaign. “This is the main place where the foreign delegations are brought to,” says Amlekya. “All foreign people who come to the museum start understanding a bit more what is going on. As for me, the biggest emotional impact is made by our bomb shelter there, our basement, where it even smells specifically.”

These foreign delegations might include presidents, prime ministers, and cabinet officials on whose support Ukraine relies. Visits are often combined with trips to damaged parts of Irpin and Bucha. In June 2022, for instance, the leaders of France, Germany, and Italy were shown both the museum and Irpin. It is impossible to show a causal link, but this visit came shortly before the United States and European allies drastically increased their supplies of artillery to Ukraine, particularly the HIMARs rocket launchers that were crucial to later Ukrainian counter-offensive successes. “Based on this example we can show to the international community and all the delegations how civilian people are living and surviving here during the war, and why we do need their support and weapons,” Amlekya says.

No matter how the war ends, all of Ukraine will have been profoundly changed. Countless Ukrainian cities, such as Bakhmut, Severodonetsk, and Mariupol, suffered the same deprivations as Hostomel, but remain under occupation so their stories can only be told from a distance, for now. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians have been killed, and millions displaced, but someday the war will end. Fiks wants to ensure that her project reminds future generations of what the country went through in these dark times. “The cubes are the DNA of our nation in the time we are going through,” she says. “We want people to remember about this war. We know that in 50 years, people will listen to the stories from this war about like we listen to stories about the Second World War from our grandparents.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook