Mary Edwards Walker and the Queer Suffragists Who Changed History

They wore pants, advocated for free love, and refused to back down.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

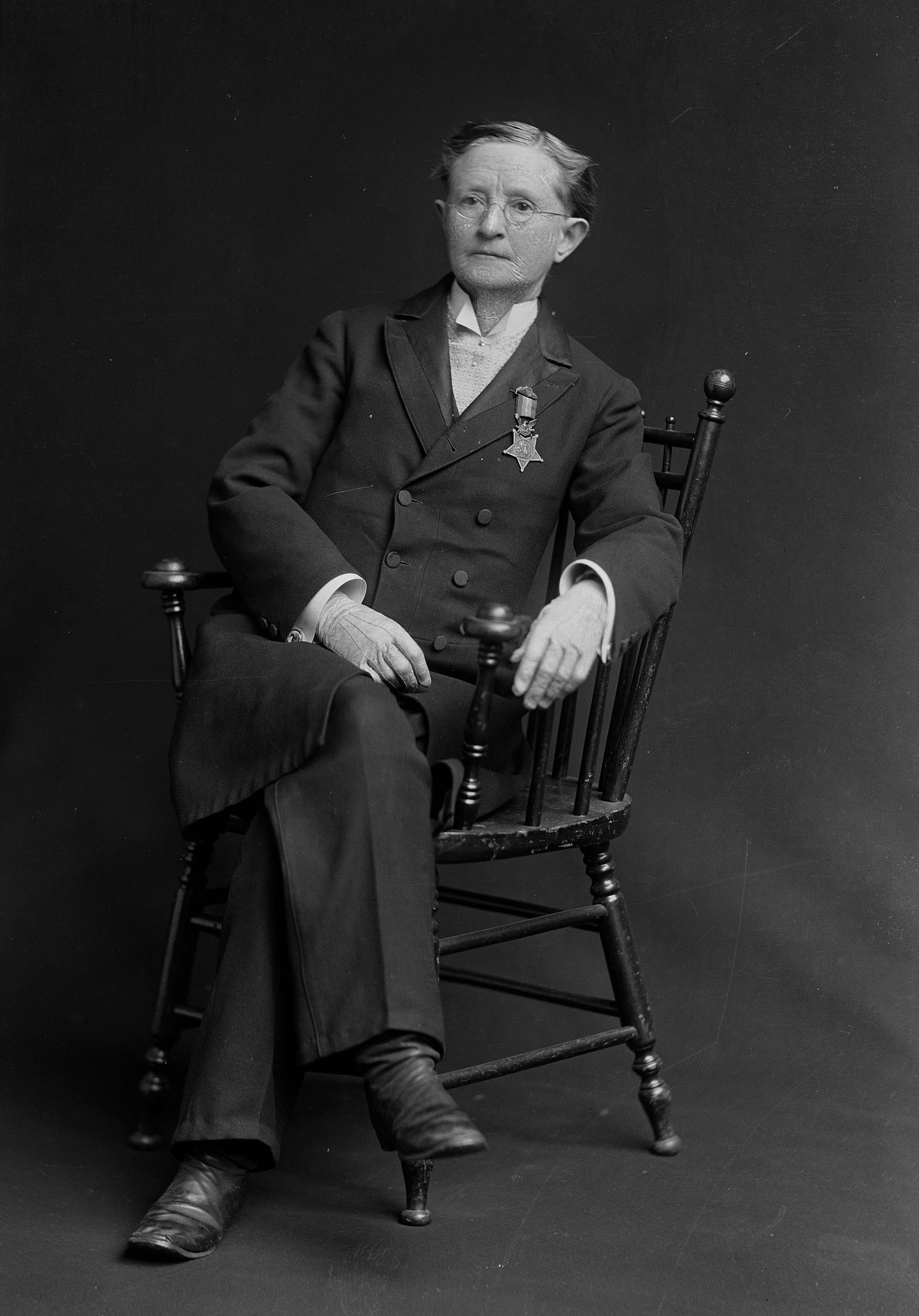

On a chilly Thursday in January 1873, hundreds of women convened at the National Hotel in Washington, D.C. It was the fifth convention of the National Woman Suffrage Association and a 44-year-old Susan B. Anthony had taken the floor. She spoke of unity, forming a national women’s newspaper, and the vote. But few people were paying attention to Anthony. Even suffragist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton was distracted, verging on annoyed. Because there, just to the side of the podium, an imposing woman stood in pants and a slimming man’s coat, waiting. Her name was Mary Edwards Walker. The first female surgeon in the U.S. Army and a prisoner of war during the Civil War, Walker, who flouted the day’s rigid gender norms, was something of a celebrity. As more and more of the crowd noticed her, they began to murmur and whisper, “she’s here!” But still Walker stood, patiently waiting for Anthony to yield the floor. When Anthony finally did so, Walker launched into a scathing critique of the NWSA, and Stanton and Anthony with it. They had abandoned the cause of dress reform, she said, giving up the fight for women to renounce health-damaging corsets. Anthony and Stanton lacked courage, she said. At a later suffrage convention, Anthony and Stanton called the cops on Walker. After narrowly avoiding arrest, Walker shouted at the pair, “you are not working for the cause, but for yourselves!”

Following the January 1873 convention, Stanton forbid any mention of Walker in the event’s official summary. Stanton and other critics derided Walker as a “she-man” and a “ghoul.” Years later, when Stanton and Anthony wrote the History of Woman Suffrage, they erased Walker and her involvement almost entirely. “They deliberately sought to conceal the queerness of the suffrage movement,” writes historian Wendy Rouse of San José State University. Rouse, who has written a new book on the topic, Public Faces, Secret Lives: A Queer History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, uncovered many stories like Walker’s. From queer relationships known as Boston marriages to publishing radical newspapers about free love, the women’s suffrage movement was full of individuals “queering the norm,” as Rouse puts it—individuals history consciously deleted. Atlas Obscura spoke with Rouse about these queer suffragists, the female cavalries they led, and why so many of their stories have gone untold.

How do you define the term “queer suffragists?”

So I use it in two ways. One is to say a broad term for the LGBTQ+ community. And so people, if they were alive today, might identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, but at the same time recognizing that those terms didn’t exist then.

But I also use the term “queer” more broadly to talk about the ways in which suffragists, whether they were lesbian, gay, bisexual, or not, shifted and challenged the gender and sexual norms of their day. So I talk about straight women in the book who are completely defying the norms by choosing never to marry or by choosing to live in these domestic arrangements with other women. When you look at it that way, then the suffrage movement is very queer, because these women are just completely challenging the heteronormative structure of their time period.

Was there something that really struck you while you were researching the book?

Just how queer it was! I went into it knowing, “okay, so there’s some queer women in the movement,” and by the end, I and I was like, “who wasn’t queer?”

Who’s your favorite queer suffragist from the book?

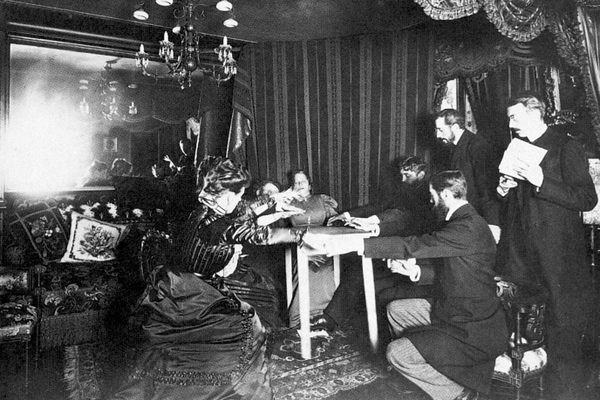

My favorite is Alice Morgan Wright. She was this younger suffragist, who got involved in the movement in college. After college, she decided to go study art in Europe. And on the steamship over to Paris, she meets Emmeline Pankhurst, who was the leader of the British militant suffrage movement. Wright was so excited to meet her that she just fell head over heels for Pankhurst. I think Pankhurst, who was much older than her, just saw Wright as one of the many fans that she had. At the time, in the early 20th century, the British suffrage movement was heating up and starting to get very agitated that the government was not doing anything. Pankhurst writes a few letters to Wright about it. And Wright just can’t help herself. She wants to be a part of that movement. So she ends up traveling to London and gets arrested with the British suffragists for trying to break a window. And she’s so excited to be imprisoned with the famous suffragists of England. She actually writes love poems on these little scraps of paper to Pankhurst while Pankhurst’s in solitary.

Wright eventually gets out of jail and comes back to the United States. She ends up meeting another suffragist named Edith Goode and they have a lifelong partnership together. But Wright was just most relatable to me because of her story of falling in love with Pankhurst—it’s a very real queer story. It’s these friendships but also these queer crushes and romantic relationships that really bind the suffragists together in common cause.

Are there any anecdotes, beyond Wright, that really stuck out to you while you were writing the book?

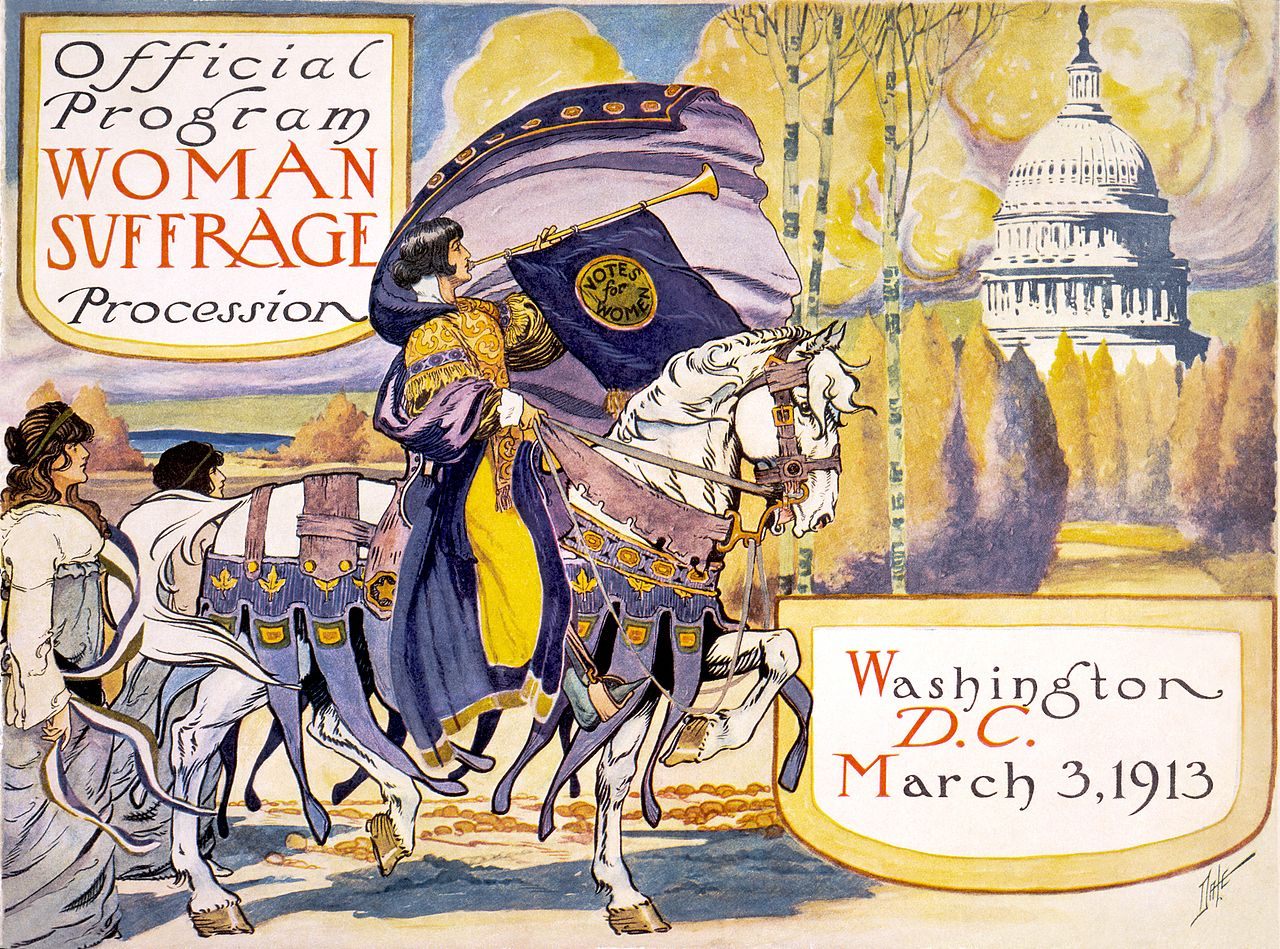

I think Annie Tinker’s really fun too. She was gender-nonconforming not only in her clothing, but just in her general attitude and behavior. She just embraced this idea that she could do whatever she wanted. She decides she’s going to not just march in the New York suffrage parade, but lead a cavalry of suffragists on horseback. And so she starts this woman’s cavalry, who are dressed in these more masculine outfits, marching down the street on horseback. The press was amused and kept referring to her as very “mannish.” But they asked her, “why are you dressed like the military and marching down the street? Do you really think women could be in the military?” and she said, “yes, we could. If we want, we should be able to.” She loved to take the spotlight and insist that she could do whatever she wanted. And she did try to join the military when World War I broke out. She was one of those suffragists that was really queering the norm.

What would you like people to understand about queer suffragists and their legacy?

I think to understand that they existed. We’re constantly combating erasure when it comes to queer history. We’re fighting for recognition that queer people existed and have always existed. They shouldn’t be erased in the past and they shouldn’t be erased in our present. I mean, the “don’t say gay” laws, right? That’s erasure happening right now. So if people walk away with nothing else then the fact that, “hey, there were queer women in the suffrage movement” that makes me very happy because it’s an acknowledgment that we’ve always been here.

What about these queer suffragists’ stories inspires you?

Just how bold some of them were. I focused a lot on Walker and Tinker because they were unapologetic in their queerness. We can be unapologetic in the ways that we defy norms in our lives. Even though Walker and Tinker may not have been remembered in the way they would have liked to, both during and after their lifetimes, they make more of an impact in some ways than the conforming members of the movement. So it’s just that idea to embrace who you are to the fullest and fight for what you believe in to the fullest.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook