The Weird History of Hand Dryers Will Blow You Away

An older model hand dryer. (Photo: Nick Douglas/flickr).

An older model hand dryer. (Photo: Nick Douglas/flickr).

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

The constant forward march of technology is visible pretty much everywhere. But perhaps the most unusual place where evolving technology has changed significantly in just a few years is in the restroom—specifically, when you have to wash your hands.

After decades where the basic concept stayed roughly the same, the hand dryer has become in some ways the most innovative piece of technology you’ll use in an average day.

Companies like Dyson, World Dryer, and Excel Dryer are in a cutthroat battle to ensure your hands are completely dry by the time you leave the restroom. If you have to dry your hands on your pants, they haven’t done their job.

It’s an unexpectedly competitive space, and with a huge market at stake in dealing with one of life’s minor annoyances, the heat is rising.

For nearly 100 years, inventors have been on a mission to kill the paper towel by replacing the process with blowing air.

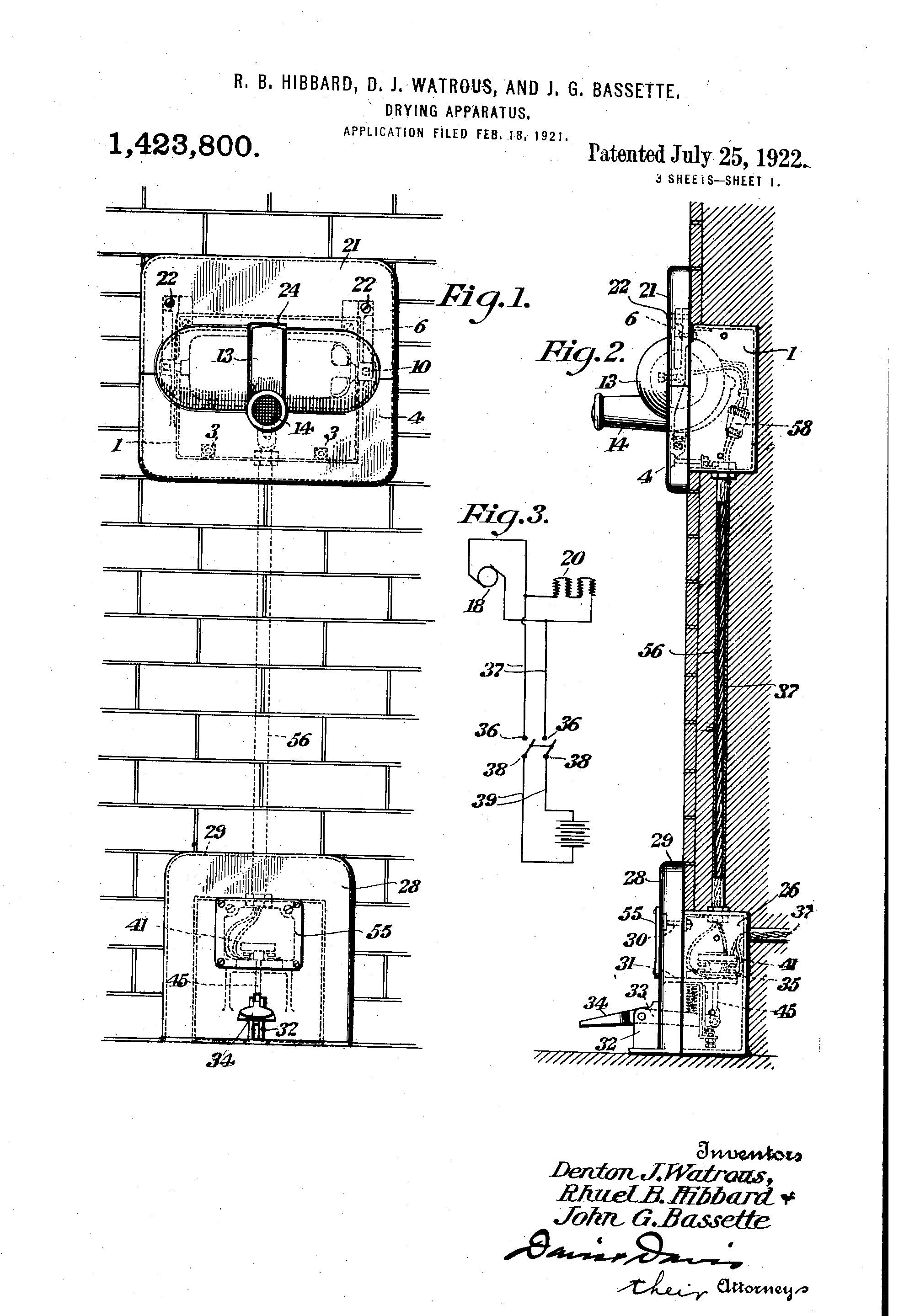

The first attempt, which came about in 1921, was called the “electric towel.” And the sad part about that is that the Airdry Corporation of New York, which patented the process, rarely even gets credit for it.

The 1922 Airdry patent for a “simple and efiicient apparatus for delivering a blast ofheated air for drying the face, hands or hair of a person, or for drying jewelry, metal parts, glassware, or other articles”. (Photo: Google Patents US1423800A)

Instead, most people start the story with George Clemens, a Chicago-based inventor who generally gets credit for inventing the device in 1949. But just because he missed out on being able to say that he invented the electric hand dryer by nearly 30 years doesn’t mean that he wasn’t skilled at inventing things. Clemens not only popularized the hand dryer, but he also created one of the first popular electric toothbrushes.

Anyway, Clemens’ work on the electric hand dryer led to the founding of World Dryer, the company that most commonly produced the devices for decades. But while they had a lock on the larger market, the company’s fairly slow rate of innovation caught up with them, and soon, their competition started to blow them away—literally.

The problem was this: While early hand dryers worked, they were loud and fairly inefficient, taking nearly a minute to dry hands. The result was that, if an air-blower was forced to compete with some nearby paper towels, the paper towels usually won.

But companies were slowly introducing new methods of automated hand-drying to the public at large.

The first big sea change came in 1993, when the Japanese automaker Mitsubishi invented a hand-dip style of drying that blows water away from your hands rather than completely evaporating it. The Mitsubishi Jet Towel didn’t reach North America until 2005.

The Dyson Airblade, released in 2006, took this basic concept even further—and quickly gained a following in bathrooms around the world, despite the fact that the vacuum maker’s devices cost $1,349 each—more than twice as much as its competition. And while Dyson’s Airblades have much of the innovative spark that the company’s vacuums and fans have, the similarities between the Airblades and Mitsubishi’s Jet Towels have led to some close competition between the two companies. (Fun fact: the Airblade’s air isn’t actually heated.)

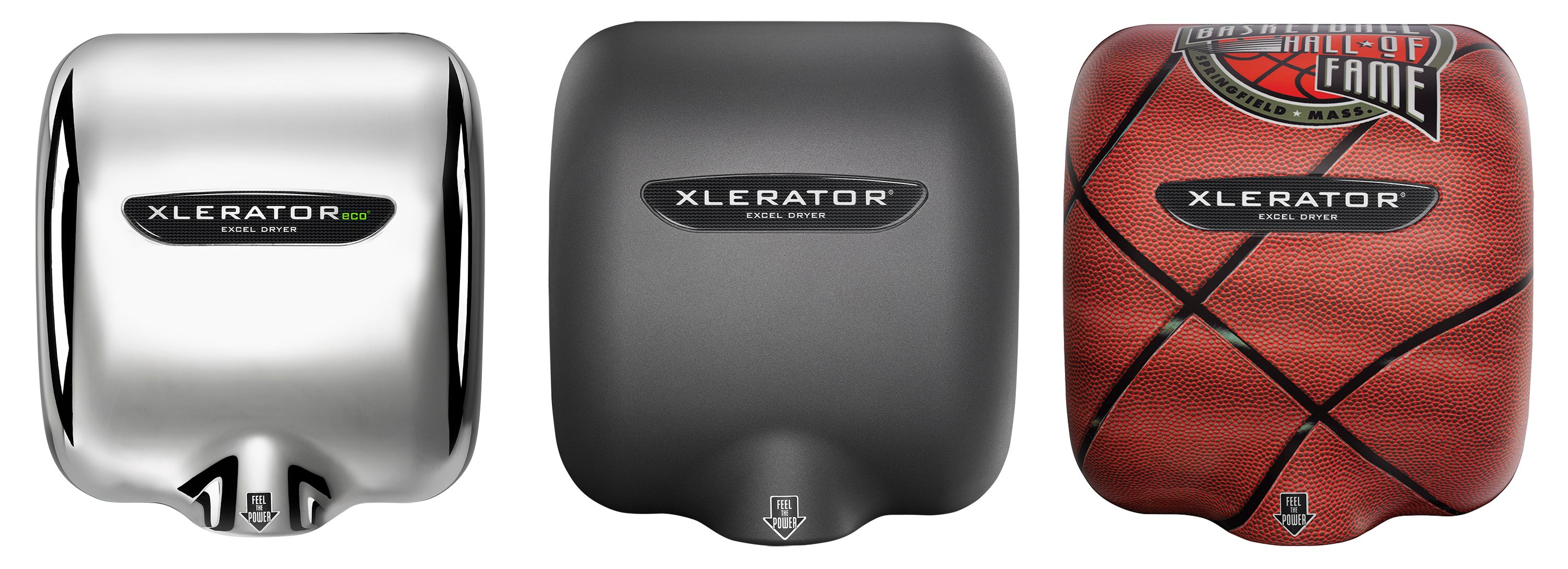

But the most innovative company in the space might be the scrappiest. In 2002, the manufacturer Excel Dryer released the Xlerator, a device that effectively dries your hands into submission. Rather than taking a minute to try your hands, the Xlerator can do the same task in just 10 to 15 seconds—making a lot of noise in the process.

Three of several finish options on the Xlerator hand dryer: chrome plated, graphite textured painted and customized. (Photo: Courtesy Excel)

The story of the Xlerator, more than that of the Airblade and the Jet Towel, highlights something of the traditional American success story. The company’s owners basically risked the company in an effort to develop a device more powerful than anything else on the market. It paid off as soon as they were able to get people to try the thing at tradeshows.

“Literally we’d have to coax people out of the aisles to come try our hand dryer,” Excel Dryer owner Denis Gagnon told NPR in 2013. “So we’d get them up to the Xlerator and they’d put hands under, and you could see the expression in their face; there was a real wow factor to it.”

The result is that Xlerators have quickly taken over the market. In fact, they’re actually kinda cocky about it. Upon the release of the Airblade in 2006, Excel director Simeon Barnes said he wasn’t even concerned about the new competition. (That didn’t stop Excel Dryer from suing Dyson for false advertising back in 2012.)

“There appears to be nothing new or unique about this product and I do not believe it poses a serious threat to our business,” Barnes told the BBC.

Of course, none of their work would’ve mattered were it not for Ignaz Semmelweis. Back in the 1840s, the Hungarian obstetrician was the man who first made the case for proper hand sanitation. Sadly, he barely earned proper respect for it while he was still alive.

Now, to be fair, Ignaz Semmelweis who had some problems with decorum, and was famous for a certain level of arrogance. But just because he was arrogant doesn’t mean he was wrong about how washing one’s hands can stop the spread of germs.

An 1860 engraving of Ignaz Semmelweis. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An 1860 engraving of Ignaz Semmelweis. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Semmelweis was trying to figure out why the maternal death rate was so much worse for the mothers of babies born in hospitals than it was for those who used midwives. Eventually, he figured out that something might be up with the way that doctors handled their patients.

He didn’t know exactly why—while he had an understanding of the basic issues, he used the phrase “morbid poison” to explain what was happening. (For the medical students in the room, the root cause was the spread of Group A hemolytic streptococcus.) Eventually, he figured out that the issue had something to do with the autopsies that medical students were doing on the deceased—just before they were to assist mothers entering the hospital.

Soon, he had the students wash their hands with a chlorine-lime solution before they worked on other patients. And soon enough, the maternal death rates at the hospital dropped.

However, while Semmelweis’ methods may have shown results, they proved controversial within the medical community, especially in Vienna, where many doctors considered his theories nonsense—despite the fact that he clearly followed the scientific method. Part of the problem might have been the implication that doctors were unknowingly putting young mothers at risk.

On top of all that, Semmelweis refused to actually share his research with the world because he considered the results so obvious. It took him 13 years to finally publish The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever, a document which reads as the best told-ya-so document in medical history.

“Since the chlorine washings were instituted with such dramatic success, not even the smallest additional changes in the procedures of the first clinic were adopted to which the decline in mortality could be even partially attributed,” he wrote.

Despite his research, Semmelweis died without the respect of the larger medical community—and in an even greater indignity, he died from an infection caused by the very disease he was fighting against.

If he had only made it a couple more decades, he would’ve known the truth: He was totally right.

The benefits of hand-washing have been obvious for more than a century, but the best way to dry one’s hands is still up for debate. Many public restrooms still let visitors choose between paper towels and hand-dryers.

Each have their boosters–and their detractors. Earlier this year, an Oregon state senator introduced a bill that would limit the noise that hand dryers could create, citing the reactions his autistic son would have to the devices.

“I almost didn’t bring this bill because this is not the most consequential bill of the legislative session,” Sen. Chris Edwards explained. “We all know that. But nonetheless there are those of us that just find these hand dryers to be extraordinarily obnoxious and disruptive to family members.” (The bill passed the senate easily but is currently in a holding pattern within the Oregon House.)

A Dyson Airblade in situ. (Photo: MrTinDC/flickr)

A Dyson Airblade in situ. (Photo: MrTinDC/flickr)

But the devices can have consequential benefits for companies. In a 2010 study focused on a tribal casino, The Environmental Protection Agency found that Dyson Airblades can pay for themselves within a few months with heavy usage, due to the fact that electricity costs much less than paper does. The lower amount of paper used also helps lower maintenance costs over time because trash bags need to be changed less often.

And on an environmentally friendly scale, hand dryers have a winning argument. A 2014 University of Buffalo study found that, on top of their major cost savings, Airblades also produce 42 percent fewer carbon dioxide emissions than the paper that goes into those rolls of paper towels.

They also seem more sanitary than paper towels do—but in the latter case, you might find a little extra debate. The reason for that is because paper-towel manufacturers have not sat idly by while the Airblade and the Xlerator have been making lots of noise.

In recent years, Kimberly-Clark has paid for research designed to make paper towels look like the obvious better option. This research generally finds that hand dryers breed bacteria and put the public at risk. Dyson has been quick to call out this research, which is often sponsored by groups like the European Tissue Symposium—a trade group that obviously benefits if paper wins.

Back in 2010, Dyson pointed out that one such study, conducted by the University of Westminster, wasn’t peer-reviewed. And a similar 2014 study, also sponsored by the tissue paper trade group, faced similar criticisms.

As it turns out, this isn’t such a cut-and-dried issue.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook